Intel

The current Intel logo since September 2, 2020 | |

Headquarters in Santa Clara, California, in 2023 | |

| Intel | |

| Formerly | NM Electronics/ MN Electronics (1968) |

| Company type | Public |

| Industry | |

| Founded | July 18, 1968 |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | , |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Frank D. Yeary (chairman) Pat Gelsinger (CEO) |

| Products | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 124,800 (2023) |

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Website | intel.com |

| Footnotes / references [1][2] | |

Intel Corporation is an American multinational corporation and technology company headquartered in Santa Clara, California, and incorporated in Delaware.[3] Intel designs, manufactures, and sells computer components and related products for business and consumer markets. It is considered one of the world's largest semiconductor chip manufacturers by revenue[4][5] and ranked in the Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by revenue for nearly a decade, from 2007 to 2016 fiscal years, until it was removed from the ranking in 2018.[6] In 2020, it was reinstated and ranked 45th, being the 7th-largest technology company in the ranking.

Intel supplies microprocessors for most manufacturers of computer systems, and is one of the developers of the x86 series of instruction sets found in most personal computers (PCs). It also manufactures chipsets, network interface controllers, flash memory, graphics processing units (GPUs), field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs), and other devices related to communications and computing. Intel has a strong presence in the high-performance general-purpose and gaming PC market with its Intel Core line of CPUs, whose high-end models are among the fastest consumer CPUs, as well as its Intel Arc series of GPUs. The Open Source Technology Center at Intel hosts PowerTOP and LatencyTOP, and supports other open source projects such as Wayland, Mesa, Threading Building Blocks (TBB), and Xen.[7]

Intel (Integrated electronics) was founded on July 18, 1968, by semiconductor pioneers Gordon Moore (of Moore's law) and Robert Noyce, along with investor Arthur Rock, and is associated with the executive leadership and vision of Andrew Grove.[8] The company was a key component of the rise of Silicon Valley as a high-tech center,[9] as well as being an early developer of SRAM and DRAM memory chips, which represented the majority of its business until 1981. Although Intel created the world's first commercial microprocessor chip—the Intel 4004—in 1971, it was not until the success of the PC in the early 1990s that this became its primary business.

During the 1990s, the partnership between Microsoft Windows and Intel, known as "Wintel", became instrumental in shaping the PC landscape[10][11] and solidified Intel's position on the market. As a result, Intel invested heavily in new microprocessor designs in the mid to late 1990s, fostering the rapid growth of the computer industry. During this period, it became the dominant supplier of PC microprocessors, with a market share of 90%,[12] and was known for aggressive and anti-competitive tactics in defense of its market position, particularly against AMD, as well as a struggle with Microsoft for control over the direction of the PC industry.[13][14]

Since the 2000s and especially since the late 2010s, Intel has faced increasing competition, which has led to a reduction in Intel's dominance and market share in the PC market.[15] Nevertheless, with a 68.4% market share as of 2023, Intel still leads the x86 market by a wide margin.[16] In addition, Intel's ability to design and manufacture its own chips is considered a rarity in the semiconductor industry,[17] as most chip designers do not have their own production facilities and instead rely on contract manufacturers (e.g. AMD and Nvidia).[18]

Industries

[edit]Operating segments

[edit]- Client Computing Group – 51.8% of 2020 revenues – produces PC processors and related components.[19][20]

- Data Center Group – 33.7% of 2020 revenues – produces hardware components used in server, network, and storage platforms.[19]

- Internet of Things Group – 5.2% of 2020 revenues – offers platforms designed for retail, transportation, industrial, buildings and home use.[19]

- Programmable Solutions Group – 2.4% of 2020 revenues – manufactures programmable semiconductors (primarily FPGAs).[19]

Customers

[edit]In 2023, Dell accounted for about 19% of Intel's total revenues, Lenovo accounted for 11% of total revenues, and HP Inc. accounted for 10% of total revenues.[1] As of May 2024, the U.S. Department of Defense is another large customer for Intel.[21][22][23][24] In September 2024, Intel reportedly qualified for as much as $3.5 billion in federal grants to make semiconductors for the Defense Department.[25]

Market share

[edit]According to IDC, while Intel enjoyed the biggest market share in both the overall worldwide PC microprocessor market (73.3%) and the mobile PC microprocessor (80.4%) in the second quarter of 2011, the numbers decreased by 1.5% and 1.9% compared to the first quarter of 2011.[26][27]

Intel's market share decreased significantly in the enthusiast market as of 2019,[28] and they have faced delays for their 10 nm products. According to former Intel CEO Bob Swan, the delay was caused by the company's overly aggressive strategy for moving to its next node.[29]

Historical market share

[edit]In the 1980s, Intel was among the world's top ten sellers of semiconductors (10th in 1987[30]). Along with Microsoft Windows, it was part of the "Wintel" personal computer domination in the 1990s and early 2000s. In 1992, Intel became the biggest semiconductor chip maker by revenue and held the position until 2018 when Samsung Electronics surpassed it, but Intel returned to its former position the year after.[31][32] Other major semiconductor companies include TSMC, GlobalFoundries, Texas Instruments, ASML, STMicroelectronics, United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC), Micron, SK Hynix, Kioxia, and SMIC.

Major competitors

[edit]Intel's competitors in PC chipsets included AMD, VIA Technologies, Silicon Integrated Systems, and Nvidia. Intel's competitors in networking include NXP Semiconductors, Infineon,[needs update] Broadcom Limited, Marvell Technology Group and Applied Micro Circuits Corporation, and competitors in flash memory included Spansion, Samsung Electronics, Qimonda, Kioxia, STMicroelectronics, Micron, and SK Hynix.

The only major competitor in the x86 processor market is AMD, with which Intel has had full cross-licensing agreements since 1976: each partner can use the other's patented technological innovations without charge after a certain time.[33] However, the cross-licensing agreement is canceled in the event of an AMD bankruptcy or takeover.[34]

Some smaller competitors, such as VIA Technologies, produce low-power x86 processors for small factor computers and portable equipment. However, the advent of such mobile computing devices, in particular, smartphones, has led to a decline in PC sales.[35] Since over 95% of the world's smartphones currently use processors cores designed by Arm, using the Arm instruction set, Arm has become a major competitor for Intel's processor market. Arm is also planning to make attempts at setting foot into the PC and server market, with Ampere and IBM each individually designing CPUs for servers and supercomputers.[36] The only other major competitor in processor instruction sets is RISC-V, which is an open source CPU instruction set. The major Chinese phone and telecommunications manufacturer Huawei has released chips based on the RISC-V instruction set due to US sanctions against China.[37]

Intel has been involved in several disputes regarding the violation of antitrust laws, which are noted below.

Carbon footprint

[edit]Intel reported total CO2e emissions (direct + indirect) for the twelve months ending December 31, 2020, at 2,882 Kt (+94/+3.4% y-o-y).[38] Intel plans to reduce carbon emissions 10% by 2030 from a 2020 base year.[39]

| Dec. 2017 | Dec. 2018 | Dec. 2019 | Dec. 2020 | Dec. 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,461[40] | 2,578[41] | 2,788[42] | 2,882[38] | 3,274[43] |

Manufacturing locations

[edit]Intel has self-reported that they have Wafer fabrication plants in the United States, Ireland, and Israel. They have also self-reported that they have assembly and testing sites mostly in China, Costa Rica, Malaysia, and Vietnam, and one site in the United States.[44][45]

Corporate history

[edit]Origins

[edit]

Intel was incorporated in Mountain View, California, on July 18, 1968, by Gordon E. Moore (known for "Moore's law"), a chemist; Robert Noyce, a physicist and co-inventor of the integrated circuit; and Arthur Rock, an investor and venture capitalist.[46][47][48] Moore and Noyce had left Fairchild Semiconductor, where they were part of the "traitorous eight" who founded it. There were originally 500,000 shares outstanding of which Dr. Noyce bought 245,000 shares, Dr. Moore 245,000 shares, and Mr. Rock 10,000 shares; all at $1 per share. Rock offered $2,500,000 of convertible debentures to a limited group of private investors (equivalent to $21 million in 2022), convertible at $5 per share.[49][50] Just 2 years later, Intel became a public company via an initial public offering (IPO), raising $6.8 million ($23.50 per share). Intel was one of the very first companies to be listed on the then-newly established National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations (NASDAQ) stock exchange.[51] Intel's third employee was Andy Grove,[note 1] a chemical engineer, who later ran the company through much of the 1980s and the high-growth 1990s.

In deciding on a name, Moore and Noyce quickly rejected "Moore Noyce",[52] near homophone for "more noise" – an ill-suited name for an electronics company, since noise in electronics is usually undesirable and typically associated with bad interference. Instead, they founded the company as NM Electronics on July 18, 1968, but by the end of the month had changed the name to Intel, which stood for Integrated Electronics.[note 2] Since "Intel" was already trademarked by the hotel chain Intelco, they had to buy the rights for the name.[51][58]

Early history

[edit]At its founding, Intel was distinguished by its ability to make logic circuits using semiconductor devices. The founders' goal was the semiconductor memory market, widely predicted to replace magnetic-core memory. Its first product, a quick entry into the small, high-speed memory market in 1969, was the 3101 Schottky TTL bipolar 64-bit static random-access memory (SRAM), which was nearly twice as fast as earlier Schottky diode implementations by Fairchild and the Electrotechnical Laboratory in Tsukuba, Japan.[59][60] In the same year, Intel also produced the 3301 Schottky bipolar 1024-bit read-only memory (ROM)[61] and the first commercial metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) silicon gate SRAM chip, the 256-bit 1101.[51][62][63]

While the 1101 was a significant advance, its complex static cell structure made it too slow and costly for mainframe memories. The three-transistor cell implemented in the first commercially available dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), the 1103 released in 1970, solved these issues. The 1103 was the bestselling semiconductor memory chip in the world by 1972, as it replaced core memory in many applications.[64][65] Intel's business grew during the 1970s as it expanded and improved its manufacturing processes and produced a wider range of products, still dominated by various memory devices.

Intel created the first commercially available microprocessor, the Intel 4004, in 1971.[51] The microprocessor represented a notable advance in the technology of integrated circuitry, as it miniaturized the central processing unit of a computer, which then made it possible for small machines to perform calculations that in the past only very large machines could do. Considerable technological innovation was needed before the microprocessor could actually become the basis of what was first known as a "mini computer" and then known as a "personal computer".[66] Intel also created one of the first microcomputers in 1973.[62][67]

Intel opened its first international manufacturing facility in 1972, in Malaysia, which would host multiple Intel operations, before opening assembly facilities and semiconductor plants in Singapore and Jerusalem in the early 1980s, and manufacturing and development centers in China, India, and Costa Rica in the 1990s.[68] By the early 1980s, its business was dominated by DRAM chips. However, increased competition from Japanese semiconductor manufacturers had, by 1983, dramatically reduced the profitability of this market. The growing success of the IBM personal computer, based on an Intel microprocessor, was among factors that convinced Gordon Moore (CEO since 1975) to shift the company's focus to microprocessors and to change fundamental aspects of that business model. Moore's decision to sole-source Intel's 386 chip played into the company's continuing success.

By the end of the 1980s, buoyed by its fortuitous position as microprocessor supplier to IBM and IBM's competitors within the rapidly growing personal computer market, Intel embarked on a 10-year period of unprecedented growth as the primary and most profitable hardware supplier to the PC industry, part of the winning 'Wintel' combination. Moore handed over his position as CEO to Andy Grove in 1987. By launching its Intel Inside marketing campaign in 1991, Intel was able to associate brand loyalty with consumer selection, so that by the end of the 1990s, its line of Pentium processors had become a household name.

Challenges to dominance (2000s)

[edit]After 2000, growth in demand for high-end microprocessors slowed. Competitors, most notably AMD (Intel's largest competitor in its primary x86 architecture market), garnered significant market share, initially in low-end and mid-range processors but ultimately across the product range, and Intel's dominant position in its core market was greatly reduced,[69] mostly due to controversial NetBurst microarchitecture. In the early 2000s then-CEO, Craig Barrett attempted to diversify the company's business beyond semiconductors, but few of these activities were ultimately successful.

Litigation

[edit]Bob had also for a number of years been embroiled in litigation. U.S. law did not initially recognize intellectual property rights related to microprocessor topology (circuit layouts), until the Semiconductor Chip Protection Act of 1984, a law sought by Intel and the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA).[70] During the late 1980s and 1990s (after this law was passed), Intel also sued companies that tried to develop competitor chips to the 80386 CPU.[71] The lawsuits were noted to significantly burden the competition with legal bills, even if Intel lost the suits.[71] Antitrust allegations had been simmering since the early 1990s and had been the cause of one lawsuit against Intel in 1991. In 2004 and 2005, AMD brought further claims against Intel related to unfair competition.

Reorganization and success with Intel Core (2005–2015)

[edit]In 2005, CEO Paul Otellini reorganized the company to refocus its core processor and chipset business on platforms (enterprise, digital home, digital health, and mobility).

On June 6, 2005, Steve Jobs, then CEO of Apple, announced that Apple would be using Intel's x86 processors for its Macintosh computers, switching from the PowerPC architecture developed by the AIM alliance.[72] This was seen as win for Intel;[73] an analyst called the move "risky" and "foolish", as Intel's current offerings at the time were considered to be behind those of AMD and IBM.[74]

In 2006, Intel unveiled its Core microarchitecture to widespread critical acclaim; the product range was perceived as an exceptional leap in processor performance that at a stroke regained much of its leadership of the field.[75][76] In 2008, Intel had another "tick" when it introduced the Penryn microarchitecture, fabricated using the 45 nm process node. Later that year, Intel released a processor with the Nehalem architecture to positive reception.[77]

On June 27, 2006, the sale of Intel's XScale assets was announced. Intel agreed to sell the XScale processor business to Marvell Technology Group for an estimated $600 million and the assumption of unspecified liabilities. The move was intended to permit Intel to focus its resources on its core x86 and server businesses, and the acquisition completed on November 9, 2006.[78]

In 2008, Intel spun off key assets of a solar startup business effort to form an independent company, SpectraWatt Inc. In 2011, SpectraWatt filed for bankruptcy.[79]

In February 2011, Intel began to build a new microprocessor manufacturing facility in Chandler, Arizona, completed in 2013 at a cost of $5 billion.[80] The building is now the 10 nm-certified Fab 42 and is connected to the other Fabs (12, 22, 32) on Ocotillo Campus via an enclosed bridge known as the Link.[81][82][83][84] The company produces three-quarters of its products in the United States, although three-quarters of its revenue come from overseas.[85]

The Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI) was launched in October 2013 and Intel is part of the coalition of public and private organizations that also includes Facebook, Google, and Microsoft. Led by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the A4AI seeks to make Internet access more affordable so that access is broadened in the developing world, where only 31% of people are online. Google will help to decrease Internet access prices so that they fall below the UN Broadband Commission's worldwide target of 5% of monthly income.[86]

Attempts at entering the smartphone market

[edit]In April 2011, Intel began a pilot project with ZTE Corporation to produce smartphones using the Intel Atom processor for China's domestic market. In December 2011, Intel announced that it reorganized several of its business units into a new mobile and communications group[87] that would be responsible for the company's smartphone, tablet, and wireless efforts. Intel planned to introduce Medfield – a processor for tablets and smartphones – to the market in 2012, as an effort to compete with Arm.[88] As a 32-nanometer processor, Medfield is designed to be energy-efficient, which is one of the core features in Arm's chips.[89]

At the Intel Developers Forum (IDF) 2011 in San Francisco, Intel's partnership with Google was announced. In January 2012, Google announced Android 2.3, supporting Intel's Atom microprocessor.[90][91][92] In 2013, Intel's Kirk Skaugen said that Intel's exclusive focus on Microsoft platforms was a thing of the past and that they would now support all "tier-one operating systems" such as Linux, Android, iOS, and Chrome.[93]

In 2014, Intel cut thousands of employees in response to "evolving market trends",[94] and offered to subsidize manufacturers for the extra costs involved in using Intel chips in their tablets. In April 2016, Intel cancelled the SoFIA platform and the Broxton Atom SoC for smartphones,[95][96][97][98] effectively leaving the smartphone market.[99][100]

Intel custom foundry

[edit]Finding itself with excess fab capacity after the failure of the Ultrabook to gain market traction and with PC sales declining, in 2013 Intel reached a foundry agreement to produce chips for Altera using a 14 nm process. General Manager of Intel's custom foundry division Sunit Rikhi indicated that Intel would pursue further such deals in the future.[101] This was after poor sales of Windows 8 hardware caused a major retrenchment for most of the major semiconductor manufacturers, except for Qualcomm, which continued to see healthy purchases from its largest customer, Apple.[102]

As of July 2013, five companies were using Intel's fabs via the Intel Custom Foundry division: Achronix, Tabula, Netronome, Microsemi, and Panasonic – most are field-programmable gate array (FPGA) makers, but Netronome designs network processors. Only Achronix began shipping chips made by Intel using the 22 nm Tri-Gate process.[103][104] Several other customers also exist but were not announced at the time.[105]

The foundry business was closed in 2018 due to Intel's issues with its manufacturing.[106][107]

Security and manufacturing challenges (2016–2021)

[edit]Intel continued its tick-tock model of a microarchitecture change followed by a die shrink until the 6th-generation Core family based on the Skylake microarchitecture. This model was deprecated in 2016, with the release of the 7th-generation Core family (codenamed Kaby Lake), ushering in the process–architecture–optimization model. As Intel struggled to shrink their process node from 14 nm to 10 nm, processor development slowed down and the company continued to use the Skylake microarchitecture until 2020, albeit with optimizations.[29]

10 nm process node issues

[edit]While Intel originally planned to introduce 10 nm products in 2016, it later became apparent that there were manufacturing issues with the node.[108] The first microprocessor under that node, Cannon Lake (marketed as 8th-generation Core), was released in small quantities in 2018.[109][110] The company first delayed the mass production of their 10 nm products to 2017.[111][112] They later delayed mass production to 2018,[113] and then to 2019. Despite rumors of the process being cancelled,[114] Intel finally introduced mass-produced 10 nm 10th-generation Intel Core mobile processors (codenamed "Ice Lake") in September 2019.[115]

Intel later acknowledged that their strategy to shrink to 10 nm was too aggressive.[29][116] While other foundries used up to four steps in 10 nm or 7 nm processes, the company's 10 nm process required up to five or six multi-pattern steps.[117] In addition, Intel's 10 nm process is denser than its counterpart processes from other foundries.[118][119] Since Intel's microarchitecture and process node development were coupled, processor development stagnated.[29]

Security flaws

[edit]In early January 2018, it was reported that all Intel processors made since 1995[120][121] (besides Intel Itanium and pre-2013 Intel Atom) had been subject to two security flaws dubbed Meltdown and Spectre.[122][123]

Renewed competition and other developments (2018–present)

[edit]Due to Intel's issues with its 10 nm process node and the company's slow processor development,[29] the company now found itself in a market with intense competition.[124] The company's main competitor, AMD, introduced the Zen microarchitecture and a new chiplet-based design to critical acclaim. Since its introduction, AMD, once unable to compete with Intel in the high-end CPU market, has undergone a resurgence,[125] and Intel's dominance and market share have considerably decreased.[126] In addition, Apple began to transition away from the x86 architecture and Intel processors to their own Apple silicon for their Macintosh computers in 2020. The transition is expected to affect Intel minimally; however, it might prompt other PC manufacturers to reevaluate their reliance on Intel and the x86 architecture.[127][128]

'IDM 2.0' strategy

[edit]On March 23, 2021, CEO Pat Gelsinger laid out new plans for the company.[129] These include a new strategy, called IDM 2.0, that includes investments in manufacturing facilities, use of both internal and external foundries, and a new foundry business called Intel Foundry Services (IFS), a standalone business unit.[130][131] Unlike Intel Custom Foundry, IFS will offer a combination of packaging and process technology, and Intel's IP portfolio including x86 cores. Other plans for the company include a partnership with IBM and a new event for developers and engineers, called "Intel ON".[107] Gelsinger also confirmed that Intel's 7 nm process is on track, and that the first products using their 7 nm process (also known as Intel 4) are Ponte Vecchio and Meteor Lake.[107]

In January 2022, Intel reportedly selected New Albany, Ohio, near Columbus, Ohio, as the site for a major new manufacturing facility.[132] The facility will cost at least $20 billion.[133] The company expects the facility to begin producing chips by 2025.[134] The same year Intel also choose Magdeburg, Germany, as a site for two new chip mega factories for €17 billion (topping Tesla's investment in Brandenburg). The start of the construction was initially planned for 2023, but this has been postponed to late 2024, while production start is planned for 2027.[135] Including subcontractors, this would create 10,000 new jobs.[136]

In August 2022, Intel signed a $30 billion partnership with Brookfield Asset Management to fund its recent factory expansions. As part of the deal, Intel would have a controlling stake by funding 51% of the cost of building new chip-making facilities in Chandler, with Brookfield owning the remaining 49% stake, allowing the companies to split the revenue from those facilities.[137][138]

On January 31, 2023, as part of $3 billion in cost reductions, Intel announced pay cuts affecting employees above midlevel, ranging from 5% upwards. It also suspended bonuses and merit pay increases, while reducing retirement plan matching. These cost reductions followed layoffs announced in the fall of 2022.[139]

In October 2023, Intel confirmed it would be the first commercial user of high-NA EUV lithography tool, as part of its plan to regain process leadership from TSMC.[140]

In August 2024, following a below-expectations Q2 earnings announcement, Intel announced "significant actions to reduce our costs. We plan to deliver $10 billion in cost savings in 2025, and this includes reducing our head count by roughly 15,000 roles, or 15% of our workforce."[141]

Artificial intelligence

[edit]In December 2023, Intel unveiled Gaudi3, an artificial intelligence (AI) chip for generative AI software which will launch in 2024 and compete with rival chips from Nvidia and AMD.[142] On 4 June 2024, Intel announced AI chips for data centers, the Xeon 6 processor, aiming for better performance and power efficiency compared to its predecessor. Intel's Gaudi 2 and Gaudi 3 AI accelerators were revealed to be more cost-effective than competitors' offerings. Additionally, Intel disclosed architecture details for its Lunar Lake processors for AI PCs,[143] which were released on September 24, 2024.

After posting $1.6 billion in loses for Q2, Intel announced in August 2024 that it intends to cut 15,000 jobs and save $10 billion in 2025.[144] In order to reach this goal, the company will offer early retirement and voluntary departure options.[145]

Shares of Intel surged before the market opened on 17 September 2024 after the chipmaker announced plans to produce custom AI chips for Amazon Web Services through its foundry division, which had been struggling. Intel also planned to cut or exit about two-thirds of its global real estate by the end of the year. As a result, Intel's shares rose nearly 7% in premarket trading.[146]

Product and market history

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

SRAMs, DRAMs, and the microprocessor

[edit]Intel's first products were shift register memory and random-access memory integrated circuits, and Intel grew to be a leader in the fiercely competitive DRAM, SRAM, and ROM markets throughout the 1970s. Concurrently, Intel engineers Marcian Hoff, Federico Faggin, Stanley Mazor, and Masatoshi Shima invented Intel's first microprocessor. Originally developed for the Japanese company Busicom to replace a number of ASICs in a calculator already produced by Busicom, the Intel 4004 was introduced to the mass market on November 15, 1971, though the microprocessor did not become the core of Intel's business until the mid-1980s. (Note: Intel is usually given credit with Texas Instruments for the almost-simultaneous invention of the microprocessor.)

In 1983, at the dawn of the personal computer era, Intel's profits came under increased pressure from Japanese memory-chip manufacturers, and then-president Andy Grove focused the company on microprocessors. Grove described this transition in the book Only the Paranoid Survive. A key element of his plan was the notion, then considered radical, of becoming the single source for successors to the popular 8086 microprocessor.

Until then, the manufacture of complex integrated circuits was not reliable enough for customers to depend on a single supplier, but Grove began producing processors in three geographically distinct factories,[which?] and ceased licensing the chip designs to competitors such as AMD.[147] When the PC industry boomed in the late 1980s and 1990s, Intel was one of the primary beneficiaries.

Early x86 processors and the IBM PC

[edit]

Despite the ultimate importance of the microprocessor, the 4004 and its successors the 8008 and the 8080 were never major revenue contributors at Intel. As the next processor, the 8086 (and its variant the 8088) was completed in 1978, Intel embarked on a major marketing and sales campaign for that chip nicknamed "Operation Crush", and intended to win as many customers for the processor as possible. One design win was the newly created IBM PC division, though the importance of this was not fully realized at the time.

IBM introduced its personal computer in 1981, and it was rapidly successful. In 1982, Intel created the 80286 microprocessor, which, two years later, was used in the IBM PC/AT. Compaq, the first IBM PC "clone" manufacturer, produced a desktop system based on the faster 80286 processor in 1985 and in 1986 quickly followed with the first 80386-based system, beating IBM and establishing a competitive market for PC-compatible systems and setting up Intel as a key component supplier.

In 1975, the company had started a project to develop a highly advanced 32-bit microprocessor, finally released in 1981 as the Intel iAPX 432. The project was too ambitious and the processor was never able to meet its performance objectives, and it failed in the marketplace. Intel extended the x86 architecture to 32 bits instead.[148][149]

386 microprocessor

[edit]During this period Andrew Grove dramatically redirected the company, closing much of its DRAM business and directing resources to the microprocessor business. Of perhaps greater importance was his decision to "single-source" the 386 microprocessor. Prior to this, microprocessor manufacturing was in its infancy, and manufacturing problems frequently reduced or stopped production, interrupting supplies to customers. To mitigate this risk, these customers typically insisted that multiple manufacturers produce chips they could use to ensure a consistent supply. The 8080 and 8086-series microprocessors were produced by several companies, notably AMD, with which Intel had a technology-sharing contract.

Grove made the decision not to license the 386 design to other manufacturers, instead, producing it in three geographically distinct factories: Santa Clara, California; Hillsboro, Oregon; and Chandler, a suburb of Phoenix, Arizona. He convinced customers that this would ensure consistent delivery. In doing this, Intel breached its contract with AMD, which sued and was paid millions of dollars in damages but could not manufacture new Intel CPU designs any longer. (Instead, AMD started to develop and manufacture its own competing x86 designs.)

As the success of Compaq's Deskpro 386 established the 386 as the dominant CPU choice, Intel achieved a position of near-exclusive dominance as its supplier. Profits from this funded rapid development of both higher-performance chip designs and higher-performance manufacturing capabilities, propelling Intel to a position of unquestioned leadership by the early 1990s.

486, Pentium, and Itanium

[edit]Intel introduced the 486 microprocessor in 1989, and in 1990 established a second design team, designing the processors code-named "P5" and "P6" in parallel and committing to a major new processor every two years, versus the four or more years such designs had previously taken. The P5 project was earlier known as "Operation Bicycle", referring to the cycles of the processor through two parallel execution pipelines. The P5 was introduced in 1993 as the Intel Pentium, substituting a registered trademark name for the former part number. (Numbers, such as 486, cannot be legally registered as trademarks in the United States.) The P6 followed in 1995 as the Pentium Pro and improved into the Pentium II in 1997. New architectures were developed alternately in Santa Clara, California and Hillsboro, Oregon.

The Santa Clara design team embarked in 1993 on a successor to the x86 architecture, codenamed "P7". The first attempt was dropped a year later but quickly revived in a cooperative program with Hewlett-Packard engineers, though Intel soon took over primary design responsibility. The resulting implementation of the IA-64 64-bit architecture was the Itanium, finally introduced in June 2001. The Itanium's performance running legacy x86 code did not meet expectations, and it failed to compete effectively with x86-64, which was AMD's 64-bit extension of the 32-bit x86 architecture (Intel uses the name Intel 64, previously EM64T). In 2017, Intel announced that the Itanium 9700 series (Kittson) would be the last Itanium chips produced.[150][151]

The Hillsboro team designed the Willamette processors (initially code-named P68), which were marketed as the Pentium 4.

During this period, Intel undertook two major supporting advertising campaigns. The first campaign, the 1991 "Intel Inside" marketing and branding campaign, is widely known and has become synonymous with Intel itself. The idea of "ingredient branding" was new at the time, with only NutraSweet and a few others making attempts to do so.[152] One of the key architects of the marketing team was the head of the microprocessor division, David House.[153] He coined the slogan "Intel Inside".[154] This campaign established Intel, which had been a component supplier little-known outside the PC industry, as a household name.

The second campaign, Intel's Systems Group, which began in the early 1990s, showcased manufacturing of PC motherboards, the main board component of a personal computer, and the one into which the processor (CPU) and memory (RAM) chips are plugged.[155] The Systems Group campaign was lesser known than the Intel Inside campaign.

Shortly after, Intel began manufacturing fully configured "white box" systems for the dozens of PC clone companies that rapidly sprang up.[156] At its peak in the mid-1990s, Intel manufactured over 15% of all PCs, making it the third-largest supplier at the time.[citation needed]

During the 1990s, Intel Architecture Labs (IAL) was responsible for many of the hardware innovations for the PC, including the PCI Bus, the PCI Express (PCIe) bus, and Universal Serial Bus (USB). IAL's software efforts met with a more mixed fate; its video and graphics software was important in the development of software digital video,[citation needed] but later its efforts were largely overshadowed by competition from Microsoft. The competition between Intel and Microsoft was revealed in testimony by then IAL Vice-president Steven McGeady at the Microsoft antitrust trial (United States v. Microsoft Corp.).

Pentium flaw

[edit]In June 1994, Intel engineers discovered a flaw in the floating-point math subsection of the P5 Pentium microprocessor. Under certain data-dependent conditions, the low-order bits of the result of a floating-point division would be incorrect. The error could compound in subsequent calculations. Intel corrected the error in a future chip revision, and under public pressure it issued a total recall and replaced the defective Pentium CPUs (which were limited to some 60, 66, 75, 90, and 100 MHz models[157]) on customer request.

The bug was discovered independently in October 1994 by Thomas Nicely, Professor of Mathematics at Lynchburg College. He contacted Intel but received no response. On October 30, he posted a message about his finding on the Internet.[158] Word of the bug spread quickly and reached the industry press. The bug was easy to replicate; a user could enter specific numbers into the calculator on the operating system. Consequently, many users did not accept Intel's statements that the error was minor and "not even an erratum". During Thanksgiving, in 1994, The New York Times ran a piece by journalist John Markoff spotlighting the error. Intel changed its position and offered to replace every chip, quickly putting in place a large end-user support organization. This resulted in a $475 million charge against Intel's 1994 revenue.[159] Dr. Nicely later learned that Intel had discovered the FDIV bug in its own testing a few months before him (but had decided not to inform customers).[160]

The "Pentium flaw" incident, Intel's response to it, and the surrounding media coverage propelled Intel from being a technology supplier generally unknown to most computer users to a household name. Dovetailing with an uptick in the "Intel Inside" campaign, the episode is considered to have been a positive event for Intel, changing some of its business practices to be more end-user focused and generating substantial public awareness, while avoiding a lasting negative impression.[161]

Intel Core

[edit]The Intel Core line originated from the original Core brand, with the release of the 32-bit Yonah CPU, Intel's first dual-core mobile (low-power) processor. Derived from the Pentium M, the processor family used an enhanced version of the P6 microarchitecture. Its successor, the Core 2 family, was released on July 27, 2006. This was based on the Intel Core microarchitecture, and was a 64-bit design.[162] Instead of focusing on higher clock rates, the Core microarchitecture emphasized power efficiency and a return to lower clock speeds.[163] It also provided more efficient decoding stages, execution units, caches, and buses, reducing the power consumption of Core 2-branded CPUs while increasing their processing capacity.

In November 2008, Intel released the 1st-generation Core processors based on the Nehalem microarchitecture. Intel also introduced a new naming scheme, with the three variants now named Core i3, i5, and i7 (as well as i9 from 7th-generation onwards). Unlike the previous naming scheme, these names no longer correspond to specific technical features. It was succeeded by the Westmere microarchitecture in 2010, with a die shrink to 32 nm and included Intel HD Graphics.

In 2011, Intel released the Sandy Bridge-based 2nd-generation Core processor family. This generation featured an 11% performance increase over Nehalem.[164] It was succeeded by Ivy Bridge-based 3rd-generation Core, introduced at the 2012 Intel Developer Forum.[165] Ivy Bridge featured a die shrink to 22 nm, and supported both DDR3 memory and DDR3L chips.

Intel continued its tick-tock model of a microarchitecture change followed by a die shrink until the 6th-generation Core family based on the Skylake microarchitecture. This model was deprecated in 2016, with the release of the 7th-generation Core family based on Kaby Lake, ushering in the process–architecture–optimization model.[166] From 2016 until 2021, Intel later released more optimizations on the Skylake microarchitecture with Kaby Lake R, Amber Lake, Whiskey Lake, Coffee Lake, Coffee Lake R, and Comet Lake.[167][168][169][170] Intel struggled to shrink their process node from 14 nm to 10 nm, with the first microarchitecture under that node, Cannon Lake (marketed as 8th-generation Core), only being released in small quantities in 2018.[109][110]

In 2019, Intel released the 10th-generation of Core processors, codenamed "Amber Lake", "Comet Lake", and "Ice Lake". Ice Lake, based on the Sunny Cove microarchitecture, was produced on the 10 nm process and was limited to low-power mobile processors. Both Amber Lake and Comet Lake were based on a refined 14 nm node, with the latter being used for desktop and high-performance mobile products and the former used for low-power mobile products.

In September 2020, 11th-generation Core mobile processors, codenamed Tiger Lake, were launched.[171] Tiger Lake is based on the Willow Cove microarchitecture and a refined 10 nm node.[172] Intel later released 11th-generation Core desktop processors (codenamed "Rocket Lake"), fabricated using Intel's 14 nm process and based on the Cypress Cove microarchitecture,[173] on March 30, 2021.[174] It replaced Comet Lake desktop processors. All 11th-generation Core processors feature new integrated graphics based on the Intel Xe microarchitecture.[175]

Both desktop and mobile products were unified under a single process node with the release of 12th-generation Intel Core processors (codenamed "Alder Lake") in late 2021.[176][177] This generation will be fabricated using Intel's 10 nm process, called Intel 7, for both desktop and mobile processors, and is based on a hybrid architecture utilizing high-performance Golden Cove cores and high-efficiency Gracemont (Atom) cores.[176]

Transient execution CPU vulnerability

[edit]Use of Intel products by Apple Inc. (2005–2019)

[edit]On June 6, 2005, Steve Jobs, then CEO of Apple, announced that Apple would be transitioning the Macintosh from its long favored PowerPC architecture to the Intel x86 architecture because the future PowerPC road map was unable to satisfy Apple's needs.[72][178] This was seen as a win for Intel,[73] although an analyst called the move "risky" and "foolish", as Intel's current offerings at the time were considered to be behind those of AMD and IBM.[74] The first Mac computers containing Intel CPUs were announced on January 10, 2006, and Apple had its entire line of consumer Macs running on Intel processors by early August 2006. The Apple Xserve server was updated to Intel Xeon processors from November 2006 and was offered in a configuration similar to Apple's Mac Pro.[179]

Despite Apple's use of Intel products, relations between the two companies were strained at times.[180] Rumors of Apple switching from Intel processors to their own designs began circulating as early as 2011.[181] On June 22, 2020, during Apple's annual WWDC, Tim Cook, Apple's CEO, announced that it would be transitioning the company's entire Mac line from Intel CPUs to custom Apple-designed processors based on the Arm architecture over the course of the next two years. In the short term, this transition was estimated to have minimal effects on Intel, as Apple only accounted for 2% to 4% of its revenue. However, at the time it was believed that Apple's shift to its own chips might prompt other PC manufacturers to reassess their reliance on Intel and the x86 architecture.[127][128] By November 2020, Apple unveiled the M1, its processor custom-designed for the Mac.[182][183][184][185]

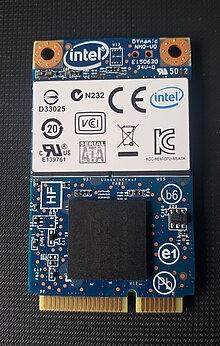

Solid-state drives (SSDs)

[edit]

In 2008, Intel began shipping mainstream solid-state drives (SSDs) with up to 160 GB storage capacities.[186] As with their CPUs, Intel develops SSD chips using ever-smaller nanometer processes. These SSDs make use of industry standards such as NAND flash,[187] mSATA,[188] PCIe, and NVMe. In 2017, Intel introduced SSDs based on 3D XPoint technology under the Optane brand name.[189]

In 2021, SK Hynix acquired most of Intel's NAND memory business[190] for $7 billion, with a remaining transaction worth $2 billion expected in 2025.[191] Intel also discontinued its consumer Optane products in 2021.[192] In July 2022, Intel disclosed in its Q2 earnings report that it would cease future product development within its Optane business, which in turn effectively discontinued the development of 3D XPoint as a whole.[193]

Supercomputers

[edit]The Intel Scientific Computers division was founded in 1984 by Justin Rattner, to design and produce parallel computers based on Intel microprocessors connected in hypercube internetwork topology.[194] In 1992, the name was changed to the Intel Supercomputing Systems Division, and development of the iWarp architecture was also subsumed.[195] The division designed several supercomputer systems, including the Intel iPSC/1, iPSC/2, iPSC/860, Paragon and ASCI Red. In November 2014, Intel stated that it was planning to use optical fibers to improve networking within supercomputers.[196]

Fog computing

[edit]On November 19, 2015, Intel, alongside Arm, Dell, Cisco Systems, Microsoft, and Princeton University, founded the OpenFog Consortium, to promote interests and development in fog computing.[197] Intel's Chief Strategist for the IoT Strategy and Technology Office, Jeff Fedders, became the consortium's first president.[198]

Self-driving cars

[edit]Intel is one of the biggest stakeholders in the self-driving car industry, having joined the race in mid 2017[199] after joining forces with Mobileye.[200] The company is also one of the first in the sector to research consumer acceptance, after an AAA report quoted a 78% nonacceptance rate of the technology in the U.S.[201]

Safety levels of autonomous driving technology, the thought of abandoning control to a machine, and psychological comfort of passengers in such situations were the major discussion topics initially. The commuters also stated that they did not want to see everything the car was doing. This was primarily a referral to the auto-steering wheel with no one sitting in the driving seat. Intel also learned that voice control regulator is vital, and the interface between the humans and machine eases the discomfort condition, and brings some sense of control back.[202] It is important to mention that Intel included only 10 people in this study, which makes the study less credible.[201] In a video posted on YouTube,[203] Intel accepted this fact and called for further testing.

Programmable devices

[edit]Intel formed a new business unit called the Programmable Solutions Group (PSG) on completion of its Altera acquisition.[204] Intel has since sold Stratix, Arria, and Cyclone FPGAs. In 2019, Intel released Agilex FPGAs: chips aimed at data centers, 5G applications, and other uses.[205]

In October 2023, Intel announced it would be spinning off PSG into a separate company at the start of 2024, while maintaining majority ownership.[206]

Competition, antitrust, and espionage

[edit]By the end of the 1990s, microprocessor performance had outstripped software demand for that CPU power.[citation needed] Aside from high-end server systems and software, whose demand dropped with the end of the "dot-com bubble",[207] consumer systems ran effectively on increasingly low-cost systems after 2000.

Intel's strategy was to develop processors with better performance in a short time, from the appearance of one to the other, as seen with the appearance of the Pentium II in May 1997, the Pentium III in February 1999, and the Pentium 4 in the fall of 2000, making the strategy ineffective since the consumer did not see the innovation as essential,[208] and leaving an opportunity for rapid gains by competitors, notably AMD. This, in turn, lowered the profitability[citation needed] of the processor line and ended an era of unprecedented dominance of the PC hardware by Intel.[citation needed]

Intel's dominance in the x86 microprocessor market led to numerous charges of antitrust violations over the years, including FTC investigations in both the late 1980s and in 1999, and civil actions such as the 1997 suit by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) and a patent suit by Intergraph. Intel's market dominance (at one time[when?] it controlled over 85% of the market for 32-bit x86 microprocessors) combined with Intel's own hardball legal tactics (such as its infamous 338 patent suit versus PC manufacturers)[209] made it an attractive target for litigation, culminating in Intel agreeing to pay AMD $1.25 billion and grant them a perpetual patent cross-license in 2009 as well as several anti-trust judgements in Europe, Korea, and Japan.[210]

A case of industrial espionage arose in 1995 that involved both Intel and AMD. Bill Gaede, an Argentine formerly employed both at AMD and at Intel's Arizona plant, was arrested for attempting in 1993 to sell the i486 and P5 Pentium designs to AMD and to certain foreign powers.[211] Gaede videotaped data from his computer screen at Intel and mailed it to AMD, which immediately alerted Intel and authorities, resulting in Gaede's arrest. Gaede was convicted and sentenced to 33 months in prison in June 1996.[212][213]

Corporate affairs

[edit]Business trends

[edit]The key trends for Intel are (as of the financial year ending in late December):[214]

| Year | Revenue (US$ bn) | Net profit (US$ bn) | Total assets (US$ bn) | Employees (k) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 62.7 | 9.6 | 123 | 102 |

| 2018 | 70.8 | 21.0 | 127 | 107 |

| 2019 | 71.9 | 21.0 | 136 | 110 |

| 2020 | 77.8 | 20.8 | 153 | 110 |

| 2021 | 79.0 | 19.8 | 168 | 121 |

| 2022 | 63.0 | 8.0 | 182 | 131 |

| 2023 | 54.2 | 1.6 | 191 | 124 |

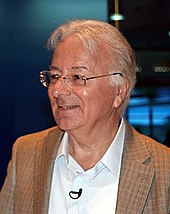

Leadership and corporate structure

[edit]

Robert Noyce was Intel's CEO at its founding in 1968, followed by co-founder Gordon Moore in 1975. Andy Grove became the company's president in 1979 and added the CEO title in 1987 when Moore became chairman. In 1998, Grove succeeded Moore as chairman, and Craig Barrett, already company president, took over. On May 18, 2005, Barrett handed the reins of the company over to Paul Otellini, who had been the company president and COO and who was responsible for Intel's design win in the original IBM PC. The board of directors elected Otellini as president and CEO, and Barrett replaced Grove as Chairman of the Board. Grove stepped down as chairman but is retained as a special adviser. In May 2009, Barrett stepped down as chairman of the board and was succeeded by Jane Shaw. In May 2012, Intel vice chairman Andy Bryant, who had held the posts of CFO (1994) and Chief Administrative Officer (2007) at Intel, succeeded Shaw as executive chairman.[215]

In November 2012, president and CEO Paul Otellini announced that he would step down in May 2013 at the age of 62, three years before the company's mandatory retirement age. During a six-month transition period, Intel's board of directors commenced a search process for the next CEO, in which it considered both internal managers and external candidates such as Sanjay Jha and Patrick Gelsinger.[216] Financial results revealed that, under Otellini, Intel's revenue increased by 55.8% (US$34.2 to 53.3 billion), while its net income increased by 46.7% (US$7.5 billion to 11 billion).[217]

On May 2, 2013, Executive Vice President and COO Brian Krzanich was elected as Intel's sixth CEO,[218] a selection that became effective on May 16, 2013, at the company's annual meeting. Reportedly, the board concluded that an insider could proceed with the role and exert an impact more quickly, without the need to learn Intel's processes, and Krzanich was selected on such a basis.[219] Intel's software head Renée James was selected as president of the company, a role that is second to the CEO position.[220]

As of May 2013, Intel's board of directors consists of Andy Bryant, John Donahoe, Frank Yeary, Ambassador Charlene Barshefsky, Susan Decker, Reed Hundt, Paul Otellini, James Plummer, David Pottruck, and David Yoffie and Creative director will.i.am. The board was described by former Financial Times journalist Tom Foremski as "an exemplary example of corporate governance of the highest order" and received a rating of ten from GovernanceMetrics International, a form of recognition that has only been awarded to twenty-one other corporate boards worldwide.[221]

On June 21, 2018, Intel announced the resignation of Brian Krzanich as CEO, with the exposure of a relationship he had with an employee. Bob Swan was named interim CEO, as the Board began a search for a permanent CEO.

On January 31, 2019, Swan transitioned from his role as CFO and interim CEO and was named by the Board as the seventh CEO to lead the company.[222]

On January 13, 2021, Intel announced that Swan would be replaced as CEO by Pat Gelsinger, effective February 15. Gelsinger is a former Intel chief technology officer who had previously been head of VMWare.[223]

In March of 2021, Intel removed the mandatory retirement age for its corporate officers.[224]

In October 2023, Intel announced it would be spinning off its Programmable Solutions Group business unit into a separate company at the start of 2024, while maintaining majority ownership and intending to seek an IPO within three years to raise funds.[206][225]

Ownership

[edit]The 10 largest shareholder of Intel as of December 2023 were:[226]

- Vanguard Group (9.12% of shares)

- BlackRock (8.04%)

- State Street (4.45%)

- Capital International (2.29%)

- Geode Capital Management (2.01%)

- Primecap (1.78%)

- Capital Research Global Investors (1.63%)

- Morgan Stanley (1.18%)

- Norges Bank (1.14%)

- Northern Trust (1.05%)

Board of directors

[edit]As of March 2023[update]:[227]

- Frank D. Yeary (chairman), managing member of Darwin Capital

- Pat Gelsinger, CEO of Intel[228]

- James Goetz, managing director of Sequoia Capital

- Andrea Goldsmith, dean of engineering and applied science at Princeton University

- Alyssa Henry, Square, Inc. executive

- Omar Ishrak, chairman and former CEO of Medtronic

- Risa Lavizzo-Mourey, former president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

- Tsu-Jae King Liu, professor at the UC Berkeley College of Engineering

- Barbara G. Novick, co-founder of BlackRock

- Gregory Smith, CFO of Boeing

- Dion Weisler, former president and CEO of HP Inc.

- Lip-Bu Tan, executive chairman of Cadence Design Systems

Employment

[edit]

Prior to March of 2021, Intel has a mandatory retirement policy for its CEOs when they reach age 65. Andy Grove retired at 62, while both Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore retired at 58. Grove retired as chairman and as a member of the board of directors in 2005 at age 68.

Intel's headquarters are located in Santa Clara, California, and the company has operations around the world. Its largest workforce concentration anywhere is in Washington County, Oregon[230] (in the Portland metropolitan area's "Silicon Forest"), with 18,600 employees at several facilities.[231] Outside the United States, the company has facilities in China, Costa Rica, Malaysia, Israel, Ireland, India, Russia, Argentina and Vietnam, in 63 countries and regions internationally. In March 2022, Intel stopped supplying the Russian market because of international sanctions during the Russo-Ukrainian War.[232] In the U.S. Intel employs significant numbers of people in California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Arizona, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Washington and Utah. In Oregon, Intel is the state's largest private employer.[231][233] The company is the largest industrial employer in New Mexico while in Arizona the company has 12,000 employees as of January 2020.[234]

Intel invests heavily in research in China and about 100 researchers – or 10% of the total number of researchers from Intel – are located in Beijing.[235]

In 2011, the Israeli government offered Intel $290 million to expand in the country. As a condition, Intel would employ 1,500 more workers in Kiryat Gat and between 600 and 1000 workers in the north.[236]

In January 2014, it was reported that Intel would cut about 5,000 jobs from its workforce of 107,000. The announcement was made a day after it reported earnings that missed analyst targets.[237]

In March 2014, it was reported that Intel would embark upon a $6 billion plan to expand its activities in Israel. The plan calls for continued investment in existing and new Intel plants until 2030. As of 2014[update], Intel employs 10,000 workers at four development centers and two production plants in Israel.[238]

Due to declining PC sales, in 2016 Intel cut 12,000 jobs.[239] In 2021, Intel reversed course under new CEO Pat Gelsinger and started hiring thousands of engineers.[240]

Diversity

[edit]Intel has a Diversity Initiative, including employee diversity groups,[241] as well as a supplier diversity program.[242] Like many companies with employee diversity groups, they include groups based on race and nationality as well as sexual identity and religion. In 1994, Intel sanctioned one of the earliest corporate Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender employee groups,[243] and supports a Muslim employees group,[244] a Jewish employees group,[245] and a Bible-based Christian group.[246][247]

Intel has received a 100% rating on numerous Corporate Equality Indices released by the Human Rights Campaign including the first one released in 2002. In addition, the company is frequently named one of the 100 Best Companies for Working Mothers by Working Mother magazine.

In January 2015, Intel announced the investment of $300 million over the next five years to enhance gender and racial diversity in their own company as well as the technology industry as a whole.[248][249][250][251][252]

In February 2016, Intel released its Global Diversity & Inclusion 2015 Annual Report.[253] The male-female mix of US employees was reported as 75.2% men and 24.8% women. For US employees in technical roles, the mix was reported as 79.8% male and 20.1% female.[253] NPR reports that Intel is facing a retention problem (particularly for African Americans), not just a pipeline problem.[254]

Economic impact in Oregon in 2009

[edit]In 2011, ECONorthwest conducted an economic impact analysis of Intel's economic contribution to the state of Oregon. The report found that in 2009 "the total economic impacts attributed to Intel's operations, capital spending, contributions and taxes amounted to almost $14.6 billion in activity, including $4.3 billion in personal income and 59,990 jobs".[255] Through multiplier effects, every 10 Intel jobs supported, on average, was found to create 31 jobs in other sectors of the economy.[256]

Supply chain

[edit]Intel has been addressing supply base reduction as an issue since the mid-1980's, adopting an "n + 1" rule of thumb, whereby the maximum number of suppliers required to maintain production levels for each component is determined, and no more than one additional supplier is engaged with for each component.[257]

Intel Israel

[edit]Intel has been operating in the State of Israel since Dov Frohman founded the Israeli branch of the company in 1974 in a small office in Haifa. Intel Israel currently has development centers in Haifa, Jerusalem and Petah Tikva, and has a manufacturing plant in the Kiryat Gat industrial park that develops and manufactures microprocessors and communications products. Intel employed about 10,000 employees in Israel in 2013. Maxine Fesberg has been the CEO of Intel Israel since 2007 and the Vice President of Intel Global. In December 2016, Fesberg announced her resignation, her position of chief executive officer (CEO) has been filled by Yaniv Gerti since January 2017.

In June 2024, the company announced that it was stopping development on a Kiryat Gat-based factory in Israel. The site was expected to cost $25 billion, with $3.2 billion provided by the Israeli government in the form of a grant.[258]

Key acquisitions and investments (2010–present)

[edit]In 2010, Intel purchased McAfee, a manufacturer of computer security technology, for $7.68 billion.[259] As a condition for regulatory approval of the transaction, Intel agreed to provide rival security firms with all necessary information that would allow their products to use Intel's chips and personal computers.[260] After the acquisition, Intel had about 90,000 employees, including about 12,000 software engineers.[261] In September 2016, Intel sold a majority stake in its computer-security unit to TPG Capital, reversing the five-year-old McAfee acquisition.[262]

In August 2010, Intel and Infineon Technologies announced that Intel would acquire Infineon's Wireless Solutions business.[263] Intel planned to use Infineon's technology in laptops, smart phones, netbooks, tablets and embedded computers in consumer products, eventually integrating its wireless modem into Intel's silicon chips.[264]

In March 2011, Intel bought most of the assets of Cairo-based SySDSoft.[265]

In July 2011, Intel announced that it had agreed to acquire Fulcrum Microsystems Inc., a company specializing in network switches.[266] The company used to be included on the EE Times list of 60 Emerging Startups.[266]

In October 2011, Intel reached a deal to acquire Telmap, an Israeli-based navigation software company. The purchase price was not disclosed, but Israeli media reported values around $300 million to $350 million.[267]

In July 2012, Intel agreed to buy 10% of the shares of ASML Holding NV for $2.1 billion and another $1 billion for 5% of the shares that need shareholder approval to fund relevant research and development efforts, as part of a EUR3.3 billion ($4.1 billion) deal to accelerate the development of 450-millimeter wafer technology and extreme ultra-violet lithography by as much as two years.[268]

In July 2013, Intel confirmed the acquisition of Omek Interactive, an Israeli company that makes technology for gesture-based interfaces, without disclosing the monetary value of the deal. An official statement from Intel read: "The acquisition of Omek Interactive will help increase Intel's capabilities in the delivery of more immersive perceptual computing experiences." One report estimated the value of the acquisition between US$30 million and $50 million.[269]

The acquisition of a Spanish natural language recognition startup, Indisys was announced in September 2013. The terms of the deal were not disclosed but an email from an Intel representative stated: "Intel has acquired Indisys, a privately held company based in Seville, Spain. The majority of Indisys employees joined Intel. We signed the agreement to acquire the company on May 31 and the deal has been completed." Indysis explains that its artificial intelligence (AI) technology "is a human image, which converses fluently and with common sense in multiple languages and also works in different platforms".[270]

In December 2014, Intel bought PasswordBox.[271]

In January 2015, Intel purchased a 30% stake in Vuzix, a smart glasses manufacturer. The deal was worth $24.8 million.[272]

In February 2015, Intel announced its agreement to purchase German network chipmaker Lantiq, to aid in its expansion of its range of chips in devices with Internet connection capability.[273]

In June 2015, Intel announced its agreement to purchase FPGA design company Altera for $16.7 billion, in its largest acquisition to date.[274] The acquisition completed in December 2015.[275]

In October 2015, Intel bought cognitive computing company Saffron Technology for an undisclosed price.[276]

In August 2016, Intel purchased deep-learning startup Nervana Systems for over $400 million.[277]

In December 2016, Intel acquired computer vision startup Movidius for an undisclosed price.[278]

In March 2017, Intel announced that they had agreed to purchase Mobileye, an Israeli developer of "autonomous driving" systems for US$15.3 billion.[279]

In June 2017, Intel Corporation announced an investment of over ₹1,100 crore (US$130 million) for its upcoming Research and Development (R&D) centre in Bangalore, India.[280]

In January 2019, Intel announced an investment of over $11 billion on a new Israeli chip plant, as told by the Israeli Finance Minister.[281]

In November 2021, Intel recruited some of the employees of the Centaur Technology division from VIA Technologies, a deal worth $125 million, and effectively acquiring the talent and knowhow of their x86 division.[282][283] VIA retained the x86 licence and associated patents, and its Zhaoxin CPU joint-venture continues.[284]

In December 2021, Intel said it will invest $7.1 billion to build a new chip-packaging and testing factory in Malaysia. The new investment will expand the operations of its Malaysian subsidiary across Penang and Kulim, creating more than 4,000 new Intel jobs and more than 5,000 local construction jobs.[285]

In December 2021, Intel announced its plan to take Mobileye automotive unit via an IPO of newly issued stock in 2022, maintaining its majority ownership of the company.[286]

In February 2022, Intel agreed to acquire Israeli chip manufacturer Tower Semiconductor for $5.4 billion.[287][288] In August 2023, Intel terminated the acquisition as it failed to obtain approval from Chinese regulators within the 18-month transaction deadline.[289][290]

In May 2022, Intel announced that they have acquired Finnish graphics technology firm Siru innovations. The firm founded by ex-AMD Qualcomm mobile GPU engineers, is focused on developing software and silicon building blocks for GPU's made by other companies and is set to join Intel's fledgling Accelerated Computing Systems and Graphics Group.[291]

In May 2022, it was announced that Ericsson and Intel are pooling research and development to create high-performing cloud RAN solutions.[buzzword] The organisations have pooled to launch a tech hub in California, U.S. The hub focuses on the benefits that Ericsson Cloud RAN and Intel technology can bring to: improving energy efficiency and network performance, reducing time to market, and monetizing new business opportunities such as enterprise applications.[292]

Ultrabook fund (2011)

[edit]In 2011, Intel Capital announced a new fund to support startups working on technologies in line with the company's concept for next-generation notebooks.[293] The company is setting aside a $300 million fund to be spent over the next three to four years in areas related to ultrabooks.[293] Intel announced the ultrabook concept at Computex in 2011. The ultrabook is defined as a thin (less than 0.8 inches [~2 cm] thick[294]) notebook that utilizes Intel processors[294] and also incorporates tablet features such as a touch screen and long battery life.[293][294]

At the Intel Developers Forum in 2011, four Taiwan ODMs showed prototype ultrabooks that used Intel's Ivy Bridge chips.[295] Intel plans to improve power consumption of its chips for ultrabooks, like new Ivy Bridge processors in 2013, which will only have 10W default thermal design power.[296]

Intel's goal for Ultrabook's price is below $1000;[294] however, according to two presidents from Acer and Compaq, this goal will not be achieved if Intel does not lower the price of its chips.[297]

Open source support

[edit]Intel has a significant participation in the open source communities since 1999.[298][self-published source] For example, in 2006 Intel released MIT-licensed X.org drivers for their integrated graphic cards of the i965 family of chipsets. Intel released FreeBSD drivers for some networking cards,[299] available under a BSD-compatible license,[300] which were also ported to OpenBSD.[300] Binary firmware files for non-wireless Ethernet devices were also released under a BSD licence allowing free redistribution.[301] Intel ran the Moblin project until April 23, 2009, when they handed the project over to the Linux Foundation. Intel also runs the LessWatts.org campaigns.[302]

However, after the release of the wireless products called Intel Pro/Wireless 2100, 2200BG/2225BG/2915ABG and 3945ABG in 2005, Intel was criticized for not granting free redistribution rights for the firmware that must be included in the operating system for the wireless devices to operate.[303] As a result of this, Intel became a target of campaigns to allow free operating systems to include binary firmware on terms acceptable to the open source community. Linspire-Linux creator Michael Robertson outlined the difficult position that Intel was in releasing to open source, as Intel did not want to upset their large customer Microsoft.[304] Theo de Raadt of OpenBSD also claimed that Intel is being "an Open Source fraud" after an Intel employee presented a distorted view of the situation at an open source conference.[305] In spite of the significant negative attention Intel received as a result of the wireless dealings, the binary firmware still has not gained a license compatible with free software principles.[306]

Intel has also supported other open source projects such as Blender[307] and Open 3D Engine.[308]

Corporate identity

[edit]Logo

[edit]Throughout its history, Intel has had three logos.

The first Intel logo, introduced in April 1969, featured the company's name stylized in all lowercase, with the letter "e" dropped below the other letters. The second logo, introduced on January 3, 2006, was inspired by the "Intel Inside" campaign, featuring a swirl around the Intel brand name.[309] The third logo, introduced on September 2, 2020, was inspired by the previous logos. It removes the swirl as well as the classic blue color in almost all parts of the logo, except for the dot in the "i".[310]

Intel Inside

[edit]Intel has become one of the world's most recognizable computer brands following its long-running Intel Inside campaign.[311] The idea for "Intel Inside" came out of a meeting between Intel and one of the major computer resellers, MicroAge.[312]

In the late 1980s, Intel's market share was being seriously eroded by upstart competitors such as AMD, Zilog, and others who had started to sell their less expensive microprocessors to computer manufacturers. This was because, by using cheaper processors, manufacturers could make cheaper computers and gain more market share in an increasingly price-sensitive market. In 1989, Intel's Dennis Carter visited MicroAge's headquarters in Tempe, Arizona, to meet with MicroAge's VP of Marketing, Ron Mion. MicroAge had become one of the largest distributors of Compaq, IBM, HP, and others and thus was a primary – although indirect – driver of demand for microprocessors. Intel wanted MicroAge to petition its computer suppliers to favor Intel chips. However, Mion felt that the marketplace should decide which processors they wanted. Intel's counterargument was that it would be too difficult to educate PC buyers on why Intel microprocessors were worth paying more for.[312]

Mion felt that the public did not really need to fully understand why Intel chips were better, they just needed to feel they were better. So Mion proposed a market test. Intel would pay for a MicroAge billboard somewhere saying, "If you're buying a personal computer, make sure it has Intel inside." In turn, MicroAge would put "Intel Inside" stickers on the Intel-based computers in their stores in that area. To make the test easier to monitor, Mion decided to do the test in Boulder, Colorado, where it had a single store. Virtually overnight, the sales of personal computers in that store dramatically shifted to Intel-based PCs. Intel very quickly adopted "Intel Inside" as its primary branding and rolled it out worldwide.[312] As is often the case with computer lore, other tidbits have been combined to explain how things evolved. "Intel Inside" has not escaped that tendency and there are other "explanations" that had been floating around.

Intel's branding campaign started with "The Computer Inside" tagline in 1990 in the U.S. and Europe. The Japan chapter of Intel proposed an "Intel in it" tagline and kicked off the Japanese campaign by hosting EKI-KON (meaning "Station Concert" in Japanese) at the Tokyo railway station dome on Christmas Day, December 25, 1990. Several months later, "The Computer Inside" incorporated the Japan idea to become "Intel Inside" which eventually elevated to the worldwide branding campaign in 1991, by Intel marketing manager Dennis Carter.[313] A case study, "Inside Intel Inside", was put together by Harvard Business School.[314] The five-note jingle was introduced in 1994 and by its tenth anniversary was being heard in 130 countries around the world. The initial branding agency for the "Intel Inside" campaign was DahlinSmithWhite Advertising of Salt Lake City.[315] The Intel swirl logo was the work of DahlinSmithWhite art director Steve Grigg under the direction of Intel president and CEO Andy Grove.[316][better source needed]

The Intel Inside advertising campaign sought public brand loyalty and awareness of Intel processors in consumer computers.[317] Intel paid some of the advertiser's costs for an ad that used the Intel Inside logo and xylo-marimba jingle.[318]

In 2008, Intel planned to shift the emphasis of its Intel Inside campaign from traditional media such as television and print to newer media such as the Internet.[319] Intel required that a minimum of 35% of the money it provided to the companies in its co-op program be used for online marketing.[319] The Intel 2010 annual financial report indicated that $1.8 billion (6% of the gross margin and nearly 16% of the total net income) was allocated to all advertising with Intel Inside being part of that.[320]

Intel jingle

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

The D♭–D♭–G♭–D♭–A♭ xylophone/marimba jingle, known as the "Intel bong",[321] used in Intel advertising was produced by Musikvergnuegen and written by Walter Werzowa, once a member of the Austrian 1980s sampling band Edelweiss.[322] The Intel jingle was made in 1994 to coincide with the launch of the Pentium. It was modified in 1999 to coincide with the launch of the Pentium III, although it overlapped with the 1994 version which was phased out in 2004. Advertisements for products featuring Intel processors with prominent MMX branding featured a version of the jingle with an embellishment (shining sound) after the final note.

The jingle was remade a second time in 2004 to coincide with the new logo change.[citation needed] Again, it overlapped with the 1999 version and was not mainstreamed until the launch of the Core processors in 2006, with the melody unchanged.

Another remake of the jingle debuted with Intel's new visual identity.[323] The company has made use of numerous variants since its rebranding in 2020 (while retaining the mainstream 2006 version).

Processor naming strategy

[edit]

In 2006, Intel expanded its promotion of open specification platforms beyond Centrino, to include the Viiv media center PC and the business desktop Intel vPro.

In mid-January 2006, Intel announced that they were dropping the long running Pentium name from their processors. The Pentium name was first used to refer to the P5 core Intel processors and was done to comply with court rulings that prevent the trademarking of a string of numbers, so competitors could not just call their processor the same name, as had been done with the prior 386 and 486 processors (both of which had copies manufactured by IBM and AMD). They phased out the Pentium names from mobile processors first, when the new Yonah chips, branded Core Solo and Core Duo, were released. The desktop processors changed when the Core 2 line of processors were released. By 2009, Intel was using a good–better–best strategy with Celeron being good, Pentium better, and the Intel Core family representing the best the company has to offer.[324]

According to spokesman Bill Calder, Intel has maintained only the Celeron brand, the Atom brand for netbooks and the vPro lineup for businesses. Since late 2009, Intel's mainstream processors have been called Celeron, Pentium, Core i3, Core i5, Core i7, and Core i9 in order of performance from lowest to highest. The 1st-generation Core products carry a 3 digit name, such as i5-750, and the 2nd-generation products carry a 4 digit name, such as the i5-2500, and from 10th-generation onwards, Intel processors will have a 5 digit name, such as i9-10900K for desktop. In all cases, a 'K' at the end of it shows that it is an unlocked processor, enabling additional overclocking abilities (for instance, 2500K). vPro products will carry the Intel Core i7 vPro processor or the Intel Core i5 vPro processor name.[325] In October 2011, Intel started to sell its Core i7-2700K "Sandy Bridge" chip to customers worldwide.[326]

Since 2010, "Centrino" is only being applied to Intel's WiMAX and Wi-Fi technologies.[325]

In 2022, Intel announced that they are dropping the Pentium and Celeron naming schemes for their desktop and laptop entry level processors. The "Intel Processor" branding will be replacing the old Pentium and Celeron naming schemes starting in 2023.[327][328]

In 2023, Intel announced that they will be dropping the 'i' in their future processor markings. For example, products such as Core i9, will now be called Core 9. Ultra will be added to the endings of processors that are in the higher end, such as Core Ultra 9.[329][330]

Typography

[edit]Neo Sans Intel is a customized version of Neo Sans based on the Neo Sans and Neo Tech, designed by Sebastian Lester in 2004.[331] It was introduced alongside Intel's rebranding in 2006. Previously, Intel used Helvetica as its standard typeface in corporate marketing.

Intel Clear is a global font announced in 2014 designed for to be used across all communications.[332][333] The font family was designed by Red Peek Branding and Dalton Maag.[334] Initially available in Latin, Greek and Cyrillic scripts, it replaced Neo Sans Intel as the company's corporate typeface.[335][336] Intel Clear Hebrew, Intel Clear Arabic were added by Dalton Maag Ltd.[337] Neo Sans Intel remained in logo and to mark processor type and socket on the packaging of Intel's processors.

In 2020, as part of a new visual identity, a new typeface, Intel One, was designed. It replaced Intel Clear as the font used by the company in most of its branding, however, it is used alongside Intel Clear typeface.[338] In logo, it replaced Neo Sans Intel typeface. However, it is still used to mark processor type and socket on the packaging of Intel's processors.

Intel Brand Book

[edit]Intel Brand Book is a book produced by Red Peak Branding as part of Intel's new brand identity campaign, celebrating the company's achievements while setting the new standard for what Intel looks, feels and sounds like.[339]

Charity

[edit]