Aleut language

| Aleut | |

|---|---|

| Unangam Tunuu Уна́ӈам тунуу́ or унаӈан умсуу | |

| Pronunciation | [uˈnaŋam tuˈnuː] |

| Native to | Alaska (Aleutian, Pribilof Islands, Alaskan Peninsula west of Stepovak Bay), Kamchatka Krai (Commander Islands) |

| Ethnicity | 7,234 Aleut |

Native speakers | <80 (2022)[1] in Alaska; extinct in Russia 2021 |

Eskaleut

| |

Early form | |

| Latin (Alaska) Cyrillic (Alaska, Russia) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | ale |

| ISO 639-3 | ale |

| Glottolog | aleu1260 |

| ELP | Aleut |

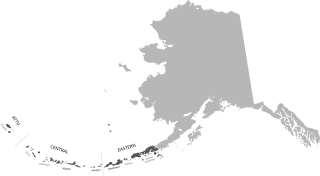

Aleut is spoken on the Aleutian Islands | |

Aleut is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

| Person | Unangax̂ |

|---|---|

| People | Unangan (east) Unangas (west) |

| Language | Unangam Tunuu |

| Country | Unangam Tanangin |

Aleut (/ˈæliuːt/ AL-ee-oot) or Unangam Tunuu[3] is the language spoken by the Aleut living in the Aleutian Islands, Pribilof Islands, Commander Islands, and the Alaska Peninsula (in Aleut Alaxsxa, the origin of the state name Alaska).[4] Aleut is the sole language in the Aleut branch of the Eskimo–Aleut language family. The Aleut language consists of three dialects, including Unalaska (Eastern Aleut), Atka/Atkan (Atka Aleut), and Attu/Attuan (Western Aleut, now extinct).[4]

Various sources estimate there are fewer than 100 to 150 remaining active Aleut speakers.[5][6][7] Because of this, Eastern and Atkan Aleut are classified as "critically endangered and extinct"[8] and have an Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (EGIDS) rating of 7.[9] The task of revitalizing Aleut has largely been left to local government and community organizations. The overwhelming majority of schools in the historically Aleut-speaking regions lack any language/culture courses in their curriculum, and those that do fail to produce fluent or even proficient speakers.[10]

History

[edit]The Eskimo and Aleut peoples were part of a migration from Asia across Beringia, the Bering land bridge between 4,000 and 6,000 years ago. During this period, the Proto-Eskimo-Aleut language was spoken, which broke up around 2000 BC. Differentiation of the two branches is thought to have happened in Alaska because of the linguistic diversity found in the Eskimo languages of Alaska relative to the entire geographic area where Eskimo languages are spoken (eastward through Canada to Greenland). After the split between the two branches, their development is thought to have occurred in relative isolation.[11]

Evidence suggests a culture associated with Aleut speakers on the Eastern Aleutian Islands as early as 4,000 years ago, followed by a gradual expansion westward over the next 1,500 years to the Near Islands.[12] Another westward expansion may have occurred about 1,000 years ago, which may explain the lack of obvious diversification among the Aleut dialects, with Eastern Aleut features having spread westward.[13] This second westward expansion is characterized as a period of cultural affinity with southeastern Alaska and the Pacific Northwest Coast,[14] which may explain linguistic features that Aleut shares with neighboring non-Eskimo languages, such as rules of plural formation.[15][16]

Due to colonization by Russian colonizers and traders in the 18th and 19th centuries, Aleut has a large portion of Russian loanwords. However, they do not affect the basic vocabulary and thus do not suggest undue influence on the language.[17]

In March 2021, the last native speaker of the Bering dialect, Vera Timoshenko, died aged 93 in Nikolskoye, Bering Island, Kamchatka.[18]

Dialects

[edit]Within the Eastern group are the dialects of the Alaskan Peninsula, Unalaska, Belkofski, Akutan, the Pribilof Islands, Kashega and Nikolski. The Pribilof dialect has more living speakers than any other dialect of Aleut.

The Atkan grouping comprises the dialects of Atka and Bering Island.

Attuan was a distinct dialect showing influence from both Atkan and Eastern Aleut. Copper Island Aleut (also called Medny Aleut) was a Russian-Attuan mixed language (Copper Island (Russian: Медный, Medny, Mednyj) having been settled by Attuans). Despite the name, after 1969 Copper Island Aleut was spoken only on Bering Island, as Copper Islanders were evacuated there. After the death of the last native speaker in 2022, it became extinct.

All dialects show lexical influence from Russian; Copper Island Aleut has also adopted many Russian inflectional endings. The largest number of Russian loanwords can be seen in the Bering Aleut.

| Bering Aleut | Russian | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| пруса̄йил (prusaajil) | прощаться (proŝatʹsâ) | take leave; tell goodbye |

| сулкуӽ (sulkux̂) | шёлк (šëlk) | silk |

| на̄нкал (naankal) | нянчить (nânčitʹ) | to nurse |

| на̄нкаӽ (naankax̂) | нянька (nânʹka) | a nurse |

| ра̄ниӽ (raanix̂) | рана (rana) | wound, injury |

| рисувал (risuval) | рисовать (risovatʹ) | to draw |

| саса̄тхиӽ (sasaatxix̂) | засада (zasada) | ambush, ambuscade |

| миса̄йал (misaajal) | мешать (mešatʹ) | to interfere |

| зӣткал (ziitkal) | жидкий (židkij) | liquid, fluid |

Orthography

[edit]The modern practical Aleut orthography was designed in 1972 for the Alaskan school system's bilingual program:[20]

| Majuscule form | Minuscule form | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| A | a | a |

| Á | á | aː |

| B* | b* | b |

| Ch | ch | t͡ʃ |

| D | d | ð |

| E* | e* | e |

| F* | f* | f |

| G | g | ɣ |

| X | x | x |

| Ĝ | ĝ | ʁ |

| X̂ | x̂ | χ |

| H | h | h |

| I | i | i |

| J | j | j |

| K | k | k |

| L | l | l |

| Hl | hl | ɬ |

| M | m | m |

| Hm | hm | m̥ |

| N | n | n |

| Hn | hn | n̥ |

| Ng ng | ng | ŋ |

| Hng hng | hng | ŋ̊ |

| O* | o* | o |

| P* | p* | p |

| Q | q | q |

| R* | r* | ɹ, ɾ |

| S | s | s |

| T | t | t |

| U | u | u |

| Uu | uu | uː |

| V* | v* | v |

| W | w | w |

| Y | y | j |

| Z† | z† | z |

- * denotes letters typically used in loanwords

- † only found in Atkan Aleut

The historic Aleut (Cyrillic) alphabet found in both Alaska and Russia has the standard pre-1918 Russian orthography as its basis, although a number of Russian letters were used only in loanwords. In addition, the extended Cyrillic letters г̑ (г with inverted breve), ҟ, ҥ, ў, х̑ (х with inverted breve) were used to represent distinctly Aleut sounds.[21][22][23]

A total of 24+ letters were used to represent distinctly Aleut words, including 6 vowels (а, и, й, у, ю, я) and 16 consonants (г, г̑, д, з, к, ԟ, л, м, н, ҥ, с, т, ў, х, х̑, ч). The letter ӄ has replaced the letter ԟ (Aleut Ka) for the voiceless uvular plosive /q/ in modern Aleut Cyrillic publications.

| Obsolete script | Modern equivalents | IPA | Practical Orthography | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majuscule | Minuscule | Majuscule | Minuscule | ||

| А | а | А | а | a | a |

| Б* | б* | Б | б | b | b |

| В* | в* | В | в | v | v |

| Г | г | Г | Г | ɣ | g |

| Г̑ | г̑ | Ӷ | ӷ | ʁ | ĝ |

| Д | д | Д̆ | д̆ | ð | d |

| Е* | е* | Е | е | e | e |

| Ж* | ж* | Ж | ж | ʒ | ž |

| З† | з† | З | з | z | z |

| И | и | И | и | i | i |

| І* | і* | i | j | ||

| Й | й | Й | й | j | y |

| К | к | К | к | k | k |

| Ԟ | ԟ | Ӄ | ӄ | q | q |

| Л | л | Л | л | l | l |

| М | м | М | м | m | m |

| Н | н | Н | н | n | n |

| Ҥ | ҥ | Ӈ | ӈ | ŋ | ng |

| О* | о* | О | о | o | o |

| П* | п* | П | п | p | p |

| Р* | р* | Р | р | ɹ, ɾ | r |

| С | с | С | с | s | s |

| Т | т | Т | т | t | t |

| У | у | У | у | u | u |

| Ў | ў | Гў | гў | w | w |

| Ф* | ф* | Ф | ф | f | f |

| Х | х | Х | х | x | x |

| Х̑ | х̑ | Ӽ | ӽ | χ | x̂ |

| Ц* | ц* | Ц | ц | t͡s | ts/c |

| Ч | ч | Ч | ч | t͡ʃ | ch |

| Ш* | ш* | Ш | ш | ʃ | |

| Щ* | щ* | Щ | щ | ʃtʃ | |

| Ъ | ъ | Ъ | ъ | ||

| Ы* | ы* | Ы | ы | j | |

| Ь | ь | Ь | ь | ||

| Э* | э* | Э | э | je | ye |

| Ю | ю | Ю | ю | ju | yu |

| Я | я | Я | я | ja | ya |

| Ѳ* | ѳ* | f | f | ||

| Ѵ* | ѵ* | i | |||

- * denotes letters typically used in loanwords

- † only found in Atkan Aleut

The modern Aleut orthography (for Bering dialect):[19]

| А а | А̄ а̄ | Б б | В в | Г г | Ӷ ӷ | Гў гў | Д д | Д̆ д̆ | Е е | Е̄ е̄ | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Ӣ ӣ |

| Й й | ʼЙ ʼй | К к | Ӄ ӄ | Л л | ʼЛ ʼл | М м | ʼМ ʼм | Н н | ʼН ʼн | Ӈ ӈ | ʼӇ ʼӈ | О о | О̄ о̄ | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ӯ ӯ | Ф ф | Х х | Ӽ ӽ | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ы̄ ы̄ | Ь ь | Э э |

| Э̄ э̄ | Ю ю | Ю̄ ю̄ | Я я | Я̄ я̄ | ʼ | ʼЎ ʼў |

| Atkan Aleut | Bering Aleut |

|---|---|

| A | А |

| Aa | А̄ |

| B | Б |

| Ch | Ч |

| D | Д̆ |

| F | Ф |

| G | Г |

| X | Х |

| Ĝ | Ӷ |

| X̂ | Ӽ |

| H | ʼ |

| I | И |

| Ii | Ӣ |

| K | К |

| L | Л |

| Hl | ʼЛ |

| M | М |

| Hm | ʼМ |

| N | Н |

| Hn | ʼН |

| Ng | Ӈ |

| Hng | ʼӇ |

| O | О |

| P | П |

| Q | Ӄ |

| R | Р |

| S | С |

| T | Т |

| U | У |

| Uu | Ӯ |

| V | В |

| W | Гў |

| Hw | ʼЎ |

| Y | Й |

| Hy | ʼЙ |

| Z | З |

Phonology

[edit]Consonants

[edit]The consonant phonemes of the various Aleut dialects are represented below. Each cell indicates the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) representation of the phoneme; consonants existing only in loanwords are in parentheses. Some phonemes are unique to specific dialects of Aleut.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palato- alveolar |

Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | voiced | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| devoiced | m̥ | n̥ | ŋ̥ | |||||

| Plosive | voiceless | (p) | t | t̺͡s̺[a] | tʃ | k | q | |

| voiced | (b) | (d) | (g) | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | (f) | θ[b] | s | ç | x | χ | |

| voiced | v[a] | ð | z[c] | ɣ | ʁ | |||

| Approximant | voiced | w | l | (ɹ, ɾ) | j | |||

| voiceless | ʍ | l̥ | h | |||||

The palato-alveolar affricate /tʃ/ and uvular stop /q/ are pronounced with strong aspiration.

Attuan labial fricative /v/ is pronounced voiced or devoiced.[3]

Voiceless approximants and devoiced nasals are preaspirated. The preaspiration of approximants causes very little friction and may pronounced more as a breathy voice. The preaspiration of devoiced nasals starts with a voiceless airstream through the nose and may end voiced before a vowel. The preaspiration feature is represented orthographically with an ⟨h⟩ preceding the given sound. For example, a devoiced, preaspirated labial nasal would be written ⟨hm⟩.[4]

Voiced approximants and nasals may be partly devoiced in contact with a voiceless consonant and at the end of a word.

The voiceless glottal approximant /h/ functions as an initial aspiration before a vowel. In Atkan and Attuan, the prevocalic /h/ aspiration contrasts with an audible but not written glottal stop initiation of the vowel. Compare halal ('to turn the head') and alal ('to need'). This contrast has been lost in Eastern Aleut.[3]

Modern Eastern Aleut has a much simpler consonant inventory because the voice contrasts among nasals, sibilants and approximants have been lost.[24]

Consonants listed in the dental column have varied places of articulation. The stop, nasal, and lateral dentals commonly have a laminal articulation. The voiced dental fricative is pronounced interdentally.[24]

The pronunciation of the sibilant /s/ varies from an alveolar articulation to a retracted articulation like a palato-alveolar consonant. There is no contrast between /s/ and ʃ in Aleut. Many Aleut speakers experience difficulties with this distinction while learning English.[24]

Vowels

[edit]| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | u | uː | |

| Open | a | aː | |||

Aleut has a basic three-vowel system including the high front /i/, low /a/, and high back /u/. Aleut vowels contrast with their long counterparts /iː/, /aː/, and /uː/.

Notably, Aleut /u/ is pronounced slightly lower than /i/ in the vowel space.

The long vowel /aː/ is pronounced retracted in the vowel space creating a significant distinction relative to the vowel length of /a/. The two high vowels are pronounced with the same vowel quality regardless of vowel length.[24]

In contact with a uvular, /i/ is lowered to [e], /a/ is backed to [ɑ], and /u/ is lowered to [o]. In contact with a coronal, /a/ is raised to [e] or [ɛ], and /u/ is fronted to [ʉ].[4][24]

The mid-vowels [ɔ] and [ɛ] occur only in family names like Nevzorof and very recently introduced Russian loanwords.

Syllable structure

[edit](C)(C)V(V) ± {C(C)(C)V(V)} ± C

An Aleut word may contain one to about a dozen syllables, all syllables with a vocalic nucleus. In Atkan and Attuan, there is a word-final CC due to apocopation. There also exist word initial CCC in loanwords.[3]

Phonotactics

[edit]A word may begin or end in a vowel, both short and long, with few exceptions. Due to apocopation, short /u/ is not found in the final position. The same is true for short /i/, except in some obsolete suffixes, such as -chi 'your' (pl.) which is realized as -chin and -chix in modern Eastern and Atkan Aleut.

Vowels within a word are separated by at least one consonant. All single consonants can appear in an intervocalic position, with the following exceptions:

- /ʍ/ and /h/ do not occur in intervocalic positions

- /w/ does not occur in contact with /u/

- /ç/ does not occur in contact with /i/

Words begin with any consonant except /θ/ and preaspirated consonants (with the exception of the preaspirated /ŋ̥/ in Atkan Aleut). Only in loanwords do /v/, /z/, and the borrowed consonants (p, b, f, d, g, ɹ/ɾ) appear word-initially.

The word-initial CC can take many forms, with various restrictions on the distribution of consonants:

- a stop or /s/, followed by a continuant other than /s/ or /z/

- a coronal stop or /s/, followed by a postlingual continuant (velar, uvular, or glottal).

- postlingual stop or /tʃ/, followed by /j/

- /k/ or /s/, followed by /n/

Intervocalic CC can occur in normal structure or as the result of syncopation.

In CC clusters of two voiced continuants, there is often a short transitional vowel. For example, qilĝix̂ 'umbilical cord' is pronounced [-liĝ-] similar to qiliĝi-n 'brain'.

Almost all possible combinations of coronal and postlingual consonants are attested.

The combination of two postlingual or two coronal consonants is rare, but attested, such as hux̂xix 'rain pants', aliĝngix̂ 'wolf', asliming 'fit for me', iistalix 'to say; to tell; to call'.

In CCC clusters, the middle consonant is either /t/, /tʃ/, /s/. For example, taxtxix̂ 'pulse', huxsx̂ilix 'to wrap up', chamchxix̂ 'short fishline'.

The most common single consonants to appear word-final are /x/, /χ/, /m/, /n/, /ŋ/, and /j/.

Through apocopation, word-final single consonants /l/ and /s/ occur, and word-final consonant clusters ending with /t/ or /s/.

Syncopation

[edit]The details of the extensive syncopation characteristic of the Eastern Aleut dialect are described below. In the examples, the syncopated vowel will be shown in parentheses.

A word medial short vowel may be syncopated between single consonants, except after an initial open short syllable and/or before a final open short syllable. For example, ìx̂am(a)nákux̂ 'it is good' and alqut(a)maan 'what for?'.

The syncopation often creates consonant clusters beyond those prescribed by the general rules of Aleut phonotactics. The resulting clusters include:

- clusters of two stops: asx̂at(i)kuu 'he killed it'

- geminate consonants: yuug(i)gaadakux̂ 'is young'

- a regular three consonant cluster: ingam(a)sxakum 'after a short while (he)'

In some frequently encountered syncopated forms, which otherwise result in irregular three consonant clusters, the middle uvular fricative is deleted along with the preceding vowel. For example, (h)iis(ax̂)talix 'saying' and (h)iil(ax̂)talix 'being said'.

At slower speeds of speech, the syncopation may not be realized. Compare txin saakutikux̂txin 'you are getting skinny' beside ting saak(u)tikuqing 'I am getting skinny'.

Stress

[edit]Aleut stress is indeterminate and often difficult to define. Stress varies based on the relation to the beginning or end of the word form, the length of the vowels, the sonority of the consonants, open- or closeness of the syllables, or the number of syllables in sentential rhythm and intonation. Stress affects the length of both vowels and consonants. Stress underlies the distinctive syncopation characteristics of Eastern Aleut. In the following discussion, the acute accent (á) indicates the stronger stress and the grave accent (à) indicates the weaker.

In Eastern Aleut, stronger stress tends to fall on the penultimate syllable if it is short (has a short vowel), or on the last syllable if it is long (has a long vowel). The weaker stress commonly falls on the first syllable. For example, úlax̂ 'house', tùnúnax̂ 'talked', tùnulákan 'without talking', ìnaqáam 'he himself'.

Eastern Aleut words with more than two syllables exhibit a wider variety of stress patterns. Stress may be attracted to another syllable by a long vowel or relatively sonorant consonant, or by a closed syllable. It is possible the stress can be determined by rhythmic factors so that one word will have different stress in different contexts, such as áĝadax̂ compared to àĝádax̂, both meaning 'arrow'.

In Atkan and Attuan Aleut, stronger stress more commonly falls on the first syllable. However, long vowels, sonorants, etc. have similar effects on stress as in Eastern Aleut. For example, qánáang 'how many' vs qánang 'where'; ùĝálux̂ 'spear' vs álaĝux̂ 'sea'.

Stress may also be expressive, as with exclamations or polite requests. Stronger stress falls on the last syllable and is accompanied by a lengthening of a short vowel. For example, kúufyax̂ àqakúx̂! 'coffee is coming'. There is a similar structure for polite requests: qadá 'please eat!' vs qáda 'eat'.

Under ordinary strong stress, a short syllable tends to be lengthened, either by lengthening the vowel or geminating the following single consonant. Lengthening of the vowel is most common in Eastern, but is found in Atkan before a voiced consonant. In all dialects gemination is common between an initial stressed syllable with a short vowel and a following stressed syllable. For example, ìláan 'from him' pronounced [-ll-] and làkáayax̂ 'a boy' pronounced [-kk-].

Phrasal phonology

[edit]The following descriptions involve phonological processes that occur in connected speech.

Word-final velar and uvular fricatives are voiceless when followed by a word-initial voiceless consonant and are voiced when followed by a word-initial voiced consonant or a vowel.

Word-final nasals /m/ and /n/ are frequently deleted before an initial consonant other than /h/. For example, tana(m) kugan 'on the ground' and ula(m) naga 'the interior of the house'.

In Eastern Aleut, the final vowel may be elided before or contracted with the initial vowel of the following word, as in aamg(ii) iĝanalix 'he is bleeding awfully'.

In Atkan, the final syllable of a word form may be clipped off in fast speech. This is even frequent at slow speed in certain constructions with auxiliary verbs. The result will be a sequence of vowels or full contraction:

- waaĝaaĝan aĝikux̂, waaĝaa-aĝikux̂, waaĝaaĝikux̂ 'he's about to come'

- ixchiinhan aĝikuq, ixchii-aĝikuq, ixchiiĝikuq 'I'll go home'

Morphology

[edit]Open word classes in Aleut include nouns and verbs, both derived from stems with suffixes. Many stems are ambivalent, being both nominal and verbal (see § Derivation). There are no adjectives other than verbal nouns and participles. Other word classes include pronouns, contrastives, quantifiers, numerals, positional nouns, demonstratives, and interrogatives.[4]

Nouns

[edit]Ordinary nouns have suffixes for [25]

- number: singular, dual, and plural

- relational case: absolutive and relative

- person: first, second, anaphoric third, reflexive third

| singular | dual | plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| absolutive | -(x̂) | -(i)x̂ | E: -(i)n A: -(i)s |

| relative | -(i)m | -(i)x̂ | E: -(i)n A: -(i)s |

| singular | dual | plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| absolutive | -a | -kix | E: -(ng)in A: -(ng)is |

| relative | -(g)an | -kin | E: -(ng)in A: -(ng)is |

The anaphoric third person refers to a proceeding term, specified by being marked in the relative case or from context. For example, tayaĝu-m ula-a 'the man's house' and ula-a 'his house'.[25]

| singular | dual | plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | ting | E: tumin A: timis |

E: tumin A: timis |

| 2nd person | txin | txidix | E: txichi A: txichix |

| reflexive 3rd person | txin | txidix | E: txidin A: txidix |

As free forms, the pronouns are used primarily as an object, like fully specified nouns. As enclitics they function as subject markers. [citation needed]

Positional nouns

[edit]Positional nouns indicate positional, directional, or some more abstract relation to a definite referent (a person or proceeding noun in relative case). Positional nouns have possessive suffixes but no inherent number. [citation needed]

Unlike ordinary nouns, positional nouns have two adverbial cases: locative and/or ablative. The most important stem i-, called the dative, has only a locative form (largely irregular) meaning 'to, at, for-'. [citation needed]

Most are used in absolutive case, as in ula-m agal-a agikux̂ 'he passed behind the house'. They can also be used in the relative case, as in laavki-m agal-a-n ula-a 'the house behind the store'.[4]

Numerals

[edit]The numeral system is decimal with hatix̂ 'ten' and sisax̂ 'hundred' as the basic higher terms. The higher tens numerals are derived through multiplication (e.g. 2 x10 for 'twenty'). The multiplicative numerals are derived with the suffix -di-m on the base numeral followed by hatix̂ 'ten'. For example, qankudim hatix̂ 'forty'.[3] [clarification needed]

| 1 | ataqan | 6 | atuung | ||||

| 2 | E: aalax A: alax |

7 | uluung | 20 | algidim | 60 | atuungidim |

| 3 | E: qaankun A: qankus |

8 | qamchiing | 30 | qankudim | 70 | uluungidim |

| 4 | E: sichin A: siching |

9 | siching | 40 | sichidim | 80 | qamchiingidim |

| 5 | chaang | 10 | hatix̂ | 50 | chaangidim | 90 | sichiingidim |

Verbs

[edit]Verbs differ from nouns morphologically by having mood/tense suffixes. Like nominal stems, verb stems may end in a short vowel or consonant. Many stems ending in a consonant had auxiliary vowels which have largely become part of the stem itself.

Negation is sometimes suffixal, preceding or combining with the mood/tense suffix. In some cases the negation will be followed by the enclitic subject pronoun.

| singular | dual | plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | E: -ku-qing A: -ku-q |

= pl. | E: -ku-n A: -ku-s |

| 2nd person | E: -ku-x̂-txin A: -kux̂t |

-ku-x̂-txidix | E: -ku-x̂-txichi(n) A: -kux̂txichix |

| 3rd person | -ku-x̂ | -ku-x | E: -ku-n A: -ku-s |

| singular | dual | plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | E: -lakaqing A: -lakaq |

= pl. | E: -lakaĝin A: -lakaĝis |

| 2nd person | E: -lakax̂-txin A: -lakax̂t |

-lakax̂-txidix | E: -lakax̂-txichi(n) A: -lakax̂txichix |

| 3rd person | -lakax̂ | -lakaĝix | E: -lakaĝin A: -lakaĝis |

Derivation (postbases)

[edit]There are 570 derivational suffixes (postbases) including many composite ones, but about two thirds are found only in a small number of words. There are approximately 175 more common suffixes, considerably less than the Eskimo branch of the family.

A postbase may be nominal or verbal, yielding nouns derived from nouns or verbs, or verbs derived from verbs or nouns, or from nominal phrases. Many stems are ambivalent, being either nominal or verbal and even some derivatives can be ambivalent.

Difficulties distinguishing between nominal and verbal parts of speech arise because the parts of speech in Aleut are not easy to distinguish. A verbal stem may be used as a verbal predicate, and quite often as a noun. The verbal use of nouns is also very common.

The derivational suffixes may combine in strings of up to about six components, some belonging together to form composites. In sequences, each successive suffix often modifies the preceding string.

The majority of derivatives have a single stem that occurs also without the suffixes in question. While some stems are bound, only occurring with some derivational suffix. For example, compare iĝa-t- 'to scare, frighten' iĝa-x̂ta- 'to fear, be afraid of' iĝa-na- 'to be terrible, frightening'.

Syntax

[edit]Overview

[edit]Most Aleut words can be classified as nouns or verbs. Notions which in English are expressed by means of adjectives and adverbs are generally expressed in Aleut using verbs or postbases (derivational suffixes).

Aleut's canonical word order is subject–object–verb (SOV).

Nouns are obligatorily marked for grammatical number (singular, dual, or plural) and for absolutive case or relative case (some researchers, notably Anna Berge, dispute both the characterization of this feature as "case" and the names absolutive and relative. This approach to Aleut nouns comes from Eskimo linguistics, but these terms can be misleading when applied to Aleut). The absolutive form is the default form, while the relative form communicates a relationship (such as possessive or contrastive) between the noun and another member of the sentence, possibly one that has been omitted. Absolutive and relative are identical in most combinations of person and number.

In possessive constructions, Aleut marks both possessor and possessum, with the possessor preceding the possessum:

tayaĝu-x̂

man-ABS

'[the] man'

ada-x̂

father-ABS

'[the] father'

tayaĝu-m

man-REL

ada-a

father-POSSM

'the man's father'

The verbal predicate of a simple sentence of the final clause of a complex sentence carries the temporal and modal marking in relation to the speech act. Verbs of non-final clauses are marked in relation to the following clause. A complex sentence may contain an unlimited number of clauses.

Simple sentences may include a subject or no subject. The predicate may be a verb with no complement, a predicate noun with a copula, or a verb with a preceding direct object in the absolutive case and/or an oblique term or local complement.

The number of arguments may be increased or decreased by verbal derivative suffixes. Arguments of a clause may be explicitly specified or anaphoric.

The verb of a simple sentence or final clause may have a nominal subject in the absolutive case or a first-/second-person subject marker. If the nominal subject is left out, as known from context, the verb implies an anaphoric reference to the subject:

tayaĝu-x̂

man-SG.ABS

awa-ku-x̂

work-PRES-SG.

The man is working

Positional nouns are a special, closed set of nouns which may take the locative or ablative noun cases; in these cases they behave essentially as postpositions. Morphosyntactically, positional noun phrases are almost identical to possessive phrases:

tayaĝu-m

man-REL

had-an

direction-LOC

'toward the man'

Verbs are inflected for mood and, if finite, for person and number. Person/number endings agree with the subject of the verb if all nominal participants of a sentence are overt:

Piitra-x̂

Peter-SG.ABS

tayaĝu-x̂

man-SG.ABS

kidu-ku-x̂.

help-PRES-3SG

'Peter is helping the man.'

If a 3rd person complement or subordinate part of it is omitted, as known from context, there is an anaphoric suffixal reference to it in the final verb and the nominal subject is in the relative case:

Piitra-m

Peter-SG.REL

kidu-ku-u.

help-PRES-3SG.ANA

'Peter is helping him.'

When more than one piece of information is omitted, the verb agrees with the element whose grammatical number is greatest. This can lead to ambiguity:

kidu-ku-ngis

help-PRES-PL.ANA

'He/she helped them.' / 'They helped him/her/them.'[26]

Comparison to Eskimo grammar

[edit]Although Aleut derives from the same parent language as the Eskimo languages, the two language groups (Aleut and Eskimo) have evolved in distinct ways, resulting in significant typological differences. Aleut inflectional morphology is greatly reduced from the system that must have been present in Proto-Eskimo–Aleut, and where the Eskimo languages mark a verb's arguments morphologically, Aleut relies more heavily on a fixed word order.

Unlike the Eskimo languages, Aleut is not an ergative-absolutive language. Subjects and objects in Aleut are not marked differently depending on the transitivity of the verb (i.e. whether the verb is transitive or intransitive); by default, both are marked with a so-called absolutive noun ending. However, if an understood complement (which may either be a complement of the verb or of some other element in the sentence) is absent, the verb takes an "anaphoric" marking and the subject noun takes a "relative" noun ending.

A typological feature shared by Aleut and Eskimo is polysynthetic derivational morphology, which can lead to some rather long words:

Ting

me

adalu-

lie-

usa-

-toward-

-naaĝ-

-try.to-

-iiĝuta-

-again-

-masu-

-perhaps-

-x̂ta-

-PFV-

-ku-

-PRES-

-x̂.

-3SG

'Perhaps he tried to fool me again.'[27]

Research history

[edit]The first contact of people from the Eastern Hemisphere with the Aleut language occurred in 1741, as Vitus Bering's expedition picked up place names and the names of the Aleut people they met. The first recording of the Aleut language in lexicon form appeared in a word list of the Unalaskan dialect compiled by Captain James King on Cook's voyage in 1778. At that time the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg became interested in the Aleut language upon hearing of Russian expeditions for trading.

In Catherine the Great's project to compile a giant comparative dictionary on all the languages spoken in what was the spread of the Russian empire at that time, she hired Peter Simon Pallas to conduct the fieldwork that would collect linguistic information on Aleut. During an expedition from 1791 to 1792, Carl Heinrich Merck and Michael Rohbeck collected several word lists and conducted a census of the male population that included prebaptismal Aleut names. Explorer Yuriy Feodorovich Lisyansky compiled several word lists. in 1804 and 1805, the czar's plenipotentiary, Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov collected some more. Johann Christoph Adelung and Johann Severin Vater published their Mithridates oder allgemeine Sprachkunde 1806–1817, which included Aleut among the languages it catalogued, similar to Catherine the Great's dictionary project.

It was not until 1819 that the first professional linguist, the Dane Rasmus Rask, studied Aleut. He collected words and paradigms from two speakers of Eastern Aleut dialects living in Saint Petersburg. In 1824 came the man who would revolutionize Aleut as a literary language. Ioann Veniaminov, a Russian Orthodox priest who would later become a saint, arrived at Unalaska studying Unalaskan Aleut. He created an orthography for this language (using the Cyrillic alphabet; the Roman alphabet would come later), translated the Gospel according to St. Matthew and several other religious works into Aleut, and published a grammar of Eastern Aleut in 1846.

The religious works were translated with the help of Veniaminov's friends Ivan Pan'kov (chief of Tigalda) and Iakov Netsvetov (the priest of Atka), both of whom were native Aleut speakers. Netsvetov also wrote a dictionary of Atkan Aleut. After Veniaminov's works were published, several religious figures took interest in studying and recording Aleut, which would help these Russian Orthodox clerics in their missionary work. Father Innocent Shayashnikov did much work in the Eastern Fox-Island dialect translating a Catechism, all four Gospels and Acts of Apostles from the New Testament, and an original composition in Aleut entitled: "Short Rule for a Pious Life".

Most of these were published in 1902, although written years earlier in the 1860s and 1870s. Father Lavrentii Salamatov produced a Catechism, and translations of three of the four Gospels (St. Mark, St. Luke, St. John) in the Western-Atkan dialect. Of Father Lavrentii's work, the Gospel of St. Mark was published in a revised orthography (1959), and in its original, bilingual Russian-Aleut format (2007), together with his Catechism for the youth of Atka Island (2007). The Atkan-dialect Gospel of St. John was also electronically published (2008), along with the Gospel of St. Luke (2009) in the original bilingual format, completing the set of Fr. Lavrentii's biblical translations.

The first Frenchman to record Aleut was Alphonse Pinart, in 1871, shortly after the United States purchase of Alaska. A French-Aleut grammar was also produced by Victor Henry, titled Esquisse d'une grammaire raisonnee de la langue aleoute d'apres la grammaire et le vocabulaire de Ivan Veniaminov (Paris, 1879). In 1878, American Lucien M. Turner began work on collecting words for a word list. Benedykt Dybowski, a Pole, began taking word lists from the dialects of the Commander Islands in 1881, while Nikolai Vasilyevich Slyunin, a Russian doctor, did the same in 1892.

From 1909 to 1910, the ethnologist Waldemar Jochelson traveled to the Aleut communities of Unalaska, Atka, Attu and Nikolski. He spent nineteen months there doing fieldwork. Jochelson collected his ethnographic work with the help of two Unalaskan speakers, Aleksey Yachmenev and Leontiy Sivtsov. He recorded many Aleut stories, folklore and myth, and had many of them not only written down but also recorded in audio. Jochelson discovered much vocabulary and grammar when he was there, adding to the scientific knowledge of the Aleut language.

In the 1930s, two native Aleuts wrote down works that are considered breakthroughs in the use of Aleut as a literary language. Afinogen K. Ermeloff wrote down a literary account of a shipwreck in his native language, while Ardelion G. Ermeloff kept a diary in Aleut during the decade. At the same time, linguist Melville Jacobs picked up several new texts from Sergey Golley, an Atkan speaker who was hospitalized at the time.

John P. Harrington furthered research into the Pribilof Island dialect on St. Paul Island in 1941, collecting some new vocabulary along the way. In 1944, the United States Department of the Interior published The Aleut Language as part of the war effort, allowing World War II soldiers to understand the language of the Aleuts. This English–language project was based on Veniaminov's work.

In 1950, Knut Bergsland began an extensive study of Aleut, perhaps the most rigorous to date, culminating in the publication of a complete Aleut dictionary in 1994 and a descriptive grammar in 1997. Bergsland's work would not have been possible without key Aleut collaborators, especially Atkan linguist Moses Dirks.

Michael Krauss, Jeff Leer, Michael Fortescue, and Jerrold Sadock have published articles about Aleut.

Alice Taff has worked on Aleut since the 1970s. Her work constitutes the most detailed accounts of Aleut phonetics and phonology available.[citation needed]

Anna Berge conducts research on Aleut. Berge's work includes treatments of Aleut discourse structure and morphosyntax, and curricular materials for Aleut, including a conversational grammar of the Atkan dialect, co-authored with Moses Dirks.

Bering Island dialect and Mednyj Aleut language have been extensively studied by Soviet and Russian linguists: Georgy Menovshchikov, Yevgeny Golovko, Nikolay Vakhtin. A dictionary[19] and a comprehensive grammar[28] were published.

In 2005, the parish of All Saints of North America Orthodox Church began to re-publish all historic Aleut language texts from 1840–1940. Archpriest Paul Merculief (originally from the Pribilofs) of the Russian Orthodox Diocese of Alaska and the Alaska State Library Historical Collection generously contributed their linguistic skills to the restoration effort. The historic Aleut texts are available in the parish's Aleut library.[29]

Revitalization

[edit]Revitalization efforts are a recent development for the Aleut language and are mostly in the hands of the Aleuts themselves. The first evidence of the preservation of the language came in the form of written documentation at the hands of the Russian Orthodox Church missionaries. However, as the historical events and factors transpired, Aleut's falling out of favor has brought upon a necessity for action if the language is to survive much longer. Linguistic experts have been reaching out to the Aleut community in attempts to record and document the language from the remaining speakers. Such efforts amount to "100 hours of conversation, along with the transcription and translation in Aleut, that will be transferred to compact disks or DVDs".[30] If Aleut does go extinct, these records will allow linguists and descendants of the Aleutian people to pass on as much knowledge of the language as they can. Efforts like this to save the language are being sponsored by universities and local community interest groups, like the Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association Task Force for Language Revitalization, while government relations with the Aleut people are severely limited. Similarly to the native languages of California, the native languages of Alaska had been given little attention from the United States government. While linguists are working to record and document the language, the local Aleutian community groups are striving to preserve their language and culture by assisting the linguists and raising awareness of the Aleut population.[31]

There is an Aleut course named Unangam Qilinĝingin on Memrise.[32]

References

[edit]- ^ "How Many Speakers are There of Each Alaska Native Language?".

- ^ "Alaska State Legislature".

- ^ a b c d e f Bergsland 1994

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bergsland 1997

- ^ "Unangam Tunuu (The Aleut Language) Preservation". Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association. Archived from the original on February 24, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ "Aleut". Alaska Native Language Center. Archived from the original on 2018-01-23. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ "Alaska Native Languages: Population and Speaker Statistics". Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger". UNESCO. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "Aleut". Ethnologue. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "Sealaska Heritage Institute: Alaska Native Language Programs, January 2012". The Alaska State Legislature. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Berge, Anna (June 2016). "Eskimo-Aleut". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.9. ISBN 9780199384655.

- ^ Corbett, D., West, D., and Lefèvre, C. (2010). The people at the end of the world: The Western Aleutians project and the archaeology of Shemya Island. Anchorage: Aurora.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Woodbury, A.C. (1984). "Eskimo and Aleut languages". Handbook of North American Indians. 5.

- ^ Dumond, D. (2001). "Archaeology in the Aleut zone of Alaska, some recent research". Archaeology in the Aleut Zone of Alaska, Some Recent Research.

- ^ Leer, J. (1991). "Evidence for a Northwest Coast language area: Promiscuous number marking and periphrastic possessive constructions in Haida, Eyak, and Aleut". International Journal of American Linguistics. 57. doi:10.1086/ijal.57.2.3519765. S2CID 146863098.

- ^ Berge, Anna (2010). "Origins of linguistic diversity in the Aleutian Islands". Human Biology. 82 (5–6): 5–6. doi:10.3378/027.082.0505. PMID 21417884. S2CID 10424701.

- ^ Berge, Anna (2014). Observations on the distribution patterns of Eskimo cognates and non-cognates in the basic Aleut (Unangam Tunuu) lexicon [poster].

- ^ "Last Native Speaker Of Rare Dialect Dies In Russia". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 2021-03-08. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ a b c d Головко, Е. В. (1994). Словарь алеутско-русский и русско-алеутский (беринговский диалект) [Aleut-Russian and Russian-Aleut Dictionary (Bering dialect)]. Отд-ние изд-ва "Просвещение". p. 14. ISBN 978-5-09-002312-2.

- ^ Bergsland 1994, p. xvi.

- ^ St. Innocent (Veniaminov) (1846). Опытъ Грамматики Алеутско-Лисьевскаго языка (Grammatical Outline of the Fox Island (Eastern) Aleut Language). St. Petersburg, Russia: Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences. p. 2.

- ^ St. Innocent (Veniaminov); St. Jacob (Netsvetov) (1893) [1840]. Начатки Христіанскаго Ученія – Букварь (Beginnings of Christian Teaching – Primer). St. Petersburg, Russia: Synodal Typography.

- ^ St. Innocent (Veniaminov); St. Jacob (Netsvetov) (1893) [1846]. Алеутскій Букварь (Aleut Primer). St. Petersburg, Russia: Synodal Typography.

- ^ a b c d e Taff, Alice; et al. (2001). "Phonetic Structures of Aleut". Journal of Phonetics. 29 (3): 231–271. doi:10.1006/jpho.2001.0142. S2CID 35100326.

- ^ a b Merchant, Jason (3 May 2008). "Aleut case matters" (PDF). uchicago.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Sadock 2000.

- ^ Bergsland 1997, p. 123.

- ^ Головко, Е. В.; Вахтин, Н. Б.; Асиновский, А. С. (2009). Язык командорских алеутов: диалект острова Беринга [The language of the Commander Aleut (a dialect of Bering Island)] (in Russian). Санкт-Петербург: Наука. ISBN 978-5-02-025542-5.

- ^ "Alaskan Orthodox texts (Aleut, Alutiiq, Tlingit, Yup'ik)". Archived from the original on 2015-05-08. Retrieved 2005-07-07.

- ^ "Saving Aleut: Linguist begins new effort to preserve native Alaskan language".

- ^ "Alaska Natives Loss of Social & Cultural Integrity".

- ^ Llanes-Ortiz, Genner (2023). "Memrise for Ume Sámi and Kristang". Digital initiatives for indigenous languages. pp. 101–102. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

The success of the Kristang Memrise inspired the start of similar projects among speakers of other Indigenous languages, like Unangam Qilinĝingin in Alaska.

Bibliography

[edit]- Berge, Anna; Moses Dirks (2009). Niiĝuĝis Mataliin Tunuxtazangis: How the Atkans Talk (A Conversational Grammar). Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska.

- Bergsland, Knut (1994). Aleut Dictionary = Unangam Tunudgusii: an unabridged lexicon of the Aleutian, Pribilof, and Commander Islands Aleut language. Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska. ISBN 978-1-55500-047-9.

- Bergsland, Knut (1997). Aleut Grammar = Unangam Tunuganaan Achixaasix̂. Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska. ISBN 978-1-55500-064-6.

- Krauss, Michael E. (2007). "Native languages of Alaska". In Miyaoko, Osahito; Sakiyama, Osamu; Krauss, Michael E. (eds.). The Vanishing Voices of the Pacific Rim. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rask, Rasmus; Thalbitzer, William (1921). "The Aleutian Language Compared with Greenlandic". International Journal of American Linguistics. 2 (1/2): 40–57. doi:10.1086/463733. JSTOR 1263180.

- Sadock, Jerrold M (2000). Aleut Number Agreement. Berkeley Linguistic Society 26th Annual Meeting.

- Taff, Alice; Lorna Rozelle; Taehong Cho; Peter Ladefoged; Moses Dirks; Jacob Wegelin (2001). "Phonetic structures of Aleut". Journal of Phonetics. 29 (3): 231–271. doi:10.1006/jpho.2001.0142. ISSN 0095-4470. S2CID 35100326.

External links

[edit]- ANLA University of Alaska Fairbanks, Unangan Collections List

- Alaska Native Languages: Unangam Tunuu

- Unangam Tunuu Language Tools

- (in Russian) Aleut Language Archived 2011-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Orthodox texts in Aleut, 1826–1967 (cf. The Alaskan Orthodox Texts Project celebrates its 10th anniversary, May 2015)

- Learn and practice Unangam Tunuu on Memrise

- Unangam Tunuu Tools and Resources, small dictionary, phrases, stories in Eastern dialect with audio recordings

- The Aleut Language, Richard Henry Geoghegan, 1944; grammar and dictionary (old orthography)

- Aleut culture

- Critically endangered languages

- Aleut language

- Indigenous languages of Alaska

- Indigenous languages of the North American Arctic

- Northern Northwest Coast Sprachbund (North America)

- Languages of Russia

- Agglutinative languages

- Indigenous languages of North America

- Official languages of Alaska

- Languages written in Cyrillic script

- Eskaleut languages