Bradenton, Florida

Bradenton, Florida | |

|---|---|

City | |

Bradenton City Hall | |

| Motto: "The Friendly City"[1] | |

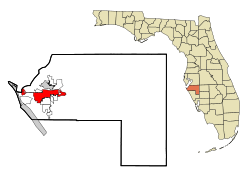

Location in Manatee County and the U.S. state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 27°29′N 82°35′W / 27.483°N 82.583°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Manatee |

| Settled | January 1842[2] |

| Incorporated (city) | May 19, 1903[3] |

| Former names |

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Gene Brown[4] |

| • Vice Mayor | Marianne Barnebey |

| • Councilors | Jayne Kocher, Josh Cramer, Lisa Gonzalez Moore, and Pam Coachman |

| • City Administrator | Rob Perry |

| • City Clerk | Tamara Melton |

| Area | |

• City | 17.50 sq mi (45.32 km2) |

| • Land | 14.34 sq mi (37.13 km2) |

| • Water | 3.16 sq mi (8.19 km2) 16.14% |

| Elevation | 6 ft (1.83 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 55,698 |

| • Density | 3,884.64/sq mi (1,499.90/km2) |

| • Urban | 779,075 (US: 57th) |

| • Urban density | 1,927.1/sq mi (744.0/km2) |

| • Metro | 859,760 (US: 70th) |

| Time zone | UTC-5:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 34201–34212, 34280–34282 |

| Area code | 941 |

| FIPS code | 12-07950[6] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0279311[7] |

| Website | cityofbradenton |

Bradenton (/ˈbreɪdəntən/ BRAY-dən-tən) is a city in and the county seat[8] of Manatee County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city's population is 55,698, up from 49,546 at the 2010 census. It is a principal city in the North Port-Bradenton-Sarasota, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area. Downtown Bradenton is along the Manatee River and includes the Bradenton Riverwalk. Downtown Bradenton is also home to the Bishop Museum of Science and Nature.

To the south of Bradenton is Sarasota; beach communities on Anna Maria Island are to its west. The Manatee River and Palmetto on the other side of it are to its north.

History

[edit]Late 18th and early 19th centuries

[edit]A settlement established by Maroons or escaped slaves named Angola existed in Bradenton's present area starting in the late 1700s and ending in 1821. It is believed to been spread out between the Manatee River (then known as Oyster River) all the way to Sarasota Bay. The community is estimated to have had 600–750 residents in it. Angola was a rather large maroon settlement as the Manatee River at that time was too shallow for US Navy vessels to navigate. The settlement was abandoned after the Creeks who were aligned with Andrew Jackson attacked Angola.[9][10]

When the United States annexed Florida in 1821, there were two known claimants of land in the vicinity of Bradenton but neither of them was confirmed by the US federal government.[11]

Mid and late 19th century

[edit]Josiah Gates along with his family and eight slaves moved to the area where present-day Bradenton exists in January 1842 after being attracted to the area for its natural beauty. Gates thought the area would be a popular place for new settlers to arrive at because it was near Fort Brooke, and he also figured that while they were building their homes they would need a place to stay at temporarily. He built his home near present-day 15th Street East and his inn at another location naming it Gates House.[12] Gates is also credited as being the first known American settler in present-day Manatee County.[13]

Bradenton is named after Dr. Joseph Braden, whose nearby fort-like house was a refuge for early settlers during the Seminole Wars. Braden owned a sugar plantation in the area, covering 1,100 acres (450 ha) and being worked by slave labor. Dr. Joseph Braden was originally from Virginia and relocated to Leon County in Florida shortly after its annexation by the United States in 1821 where he established a cotton plantation bringing his preexisting Virginia slaves along with him. After having financial difficulties from the Panic of 1837, he tried to reestablish himself financially in Manatee County in 1843 moving to the area along with his slaves.[14] To help with the shipment of sugar grown at the plantation, he constructed a pier in present-day Downtown Bradenton where ships could dock at and pick up sugar. Where the pier met the land he constructed a stockade getting the name of Fort Braden.[15] During the Third Seminole War, on April 6, 1856, Braden's fortified home was attacked by several Seminole Indians, one of the few, albeit small, direct engagements of the war.[16] Braden was financially successful with his plantation but ended up moving back to Leon County in 1857 because of a financial panic that occurred that year.[14]

Major Alden Joseph Adams purchased 400 acres of land in 1876 between present-day Manatee Memorial Hospital and 9th Street East and build his home there in 1882. He named his three-story concrete home Villa Zanza. Alden was known for having many animals and a large amount of foliage at his home. At one point he owned over 300,000 acres of land in Manatee County. Major Alden Joseph Adams served in the Union Army during the American Civil War and eventually reached the rank of major. After the war he served in the US Secret Service and later as a newspaper correspondent for the New York Herald. He reported from Paris during the time when the Paris Commune existed. At one point he was asked to look for Dr. David Livingstone but declined and suggested that Henry Morton Stanley should look for him instead. Adams died in 1915, and his home was bought in 1924 with the intent of remodeling it. However it was not completed, and his home was demolished at some point in the late 1920s.[17][18]

William I. Turner bought 7 acres from John Crews Pelot in 1877 and create a subdivision from that land creating what is now Bradenton. The land itself was plotted by Axel Emil Broberg and it contained 19 plots on both sides of what is 12th Street West along with a cross street that is currently 3rd Avenue. Turner sold the lots building a store and a warehouse along with[19] his own home where he lived at.[20]

The town was originally spelled "Braidentown," as a spelling error was made when it applied for a post office on May 9, 1878.[21] The first bridge across Wares Creek was built in 1886.[22] The following year, Bradenton was designated the county seat after DeSoto County was formed from eastern Manatee County, as the then county seat, Pine Level, was in the new county.[23] A county courthouse was built in 1890 at Courthouse Square.[24]

20th century

[edit]First half of the 20th century

[edit]

Railroad service was extended from Palmetto across the Manatee River to Bradenton in 1902.[25] Bradenton was incorporated on May 19, 1903,[3] with 59 voting in favor of incorporating and 34 voting against it.[26] Shortly after incorporation, a local election was held to choose the city's first elected municipal officials. A.T Cornwell was elected as mayor, Robert H. Roesch as clerk and tax assessor, A.B. Murphy as treasurer and F. Dryman as tax collector along with seven city council members.[27] One of the earliest moves made by the municipal government was amending the name to "Bradentown".[28][29][30] However the name change would not be reflected with the US Postal Service until 1905.[31] On December 29, a streetcar line began operation going from Bradenton to the neighboring city of Manatee and went west crossing Wares Creek to the nearby community of Fogartyville.[32][33] The company operating the line had financial difficulties, likely due to a lack of ridership, and cancelled the line in 1906.[34][35] The Manavista Hotel was opened in January 1907 bordering the Manatee River on Main Street.[36]

The Davis Bridge, the first general traffic bridge across the Manatee River was opened in June 1910. It was a wooden toll bridge built by C.H. Davis that had one lane and passing spots. The bridge went from present-day 9th Street East (located within then nearby Manatee) to near where the Atwood Grapefruit Groves were located at west of Ellenton.[37] In 1912, the first road, Range Road leading from present-day Bradenton (then, Manatee) to Sarasota was built.[33] Also during that year, the original county courthouse was bought and moved to a new location becoming a grade school for black students in the area, Lincoln Academy Grammar School. A new courthouse was built on the site of the old one which still stands today in the following year, 1913.[24] The Victory Bridge was opened in August 1919 running from current 10th Street West in Bradenton to 8th Avenue in Palmetto. Funding for the bridge came from bond issues by both Bradenton and Palmetto. The bridge itself had two lanes and was made of wood. Its name came from the United States' recent victory in World War I against the Central Powers.[38] With the Victory Bridge's construction, the municipal government of Manatee attempted to buy Davis Bridge and make it public as a way to compete with Bradenton's Victory Bridge but the deal however never went through.[37] The rest of the bridge ended up being dismantled with the exception of its draw section which was sold to county government and put into use for the Snead Island's Cut off bridge in 1920.[38]

1920s and 1930s

[edit]Baseball spring training began in Bradenton with the construction of Ninth Street Park in 1923. The first team to train in the city was the St. Louis Cardinals, doing so for 1923 and 1924. The city council began the process of removing the "w" letter from its then name "Bradentown" in January 1925 and be completed on May 2, 1925, when the state Governor signed a bill relating to it making it official.[21] All streets in the city were renamed in 1926 with a numbering system.[39]

After the collapse of the Florida land boom and the Great Depression starting, the city faced an economic downturn.[40] Along with an economic downturn, the city had financial issues as well with the city going into debt. During the Florida land boom, Bradenton borrowed money as a way to pay for infrastructure to areas that were considered outlying. As a result, the city retracted its municipal boundaries so it could not provide services to those areas and defaulted their municipal bonds as a result. After the municipal boundaries were retracted, the bonds were refunded, and residents who lived in the new boundaries would be responsible for paying it. Bradenton ended up eventually getting its bonds paid off.[41] Despite the economic downtown, several new projects were done in the city. A municipal pier (interchangeably referred to as Memorial pier) was built in 1927 with a building at its end. The pier itself still stands and the building at its end has served a variety of functions ever since.[42] As the Victory Bridge was deemed too unsafe to use after a hurricane hit it in 1926, the Green Bridge was built the following year in 1927 as a replacement to it. In the meantime, a ferry operated until the Green Bridge was built.[38][43] On July 22, 1931, a joint committee was appointed by the municipal city councils of Bradenton, Manatee, and Palmetto to consider and possibly even merge the three cities but nothing would come out of the committee in the end. A new post office building in 1937 was built on Manatee Avenue and 9th Street West as a Works Progress Administration project. The post office is still in operation.[44]

Compiled in the late 1930s and first published in 1939, the Florida guide listed Bradenton's population as being 5,986 and described it as:

lies opposite Palmetto on the south bank of the Manatee River. The two towns are connected by a mile-long bridge. Boom-time hotels dominate the skyline and do a thriving business in winter, when the population almost doubles. In the residential sections comfortable houses are surrounded with aged trees. The neighboring area of rich muck land normally produces two or three crops each season, making Bradenton the principal shipping center for winter vegetables on the west coast. Celery, citrus fruits, tomatoes, cabbages, eggplants, green peppers and square are the main products. [45]

— Federal Writers' Project, "Part III: The Florida Loop", Florida: A Guide to the Southernmost State (1947)

1940s

[edit]

Bradenton was affected by World War II like many other cities in Florida and the United States. During the war, Manatee County had its own Civil Defense battalion in it with two subunits existing in Bradenton and another for nearby Manatee. A recreational center was opened in March 1942 at a building on the intersection of 6th Avenue and 12th Street West in the downtown area to be used by soldiers. The recreation center closed in November 1945 and was popular with local soldiers and visited even by those who were stationed outside of Bradenton. Police Chief Clyde Benton expanded the police force by naming 45 officers to serve without pay during the war.[46] Camp Weatherford located at LECOM Field existed for eight months at some point during the war as a training center for the US Army Signal Corps. About 350 soldiers were trained there during its existence. The camp itself often had an issue with being flooded because of the rainy climate, showers at the camp occurring often, clothes being washed, its low elevation and is located nearby to Wares Creek. A soldier named Joe Grossman at the camp ran a radio show broadcasting on WSPB called Weatherford Shinings. Local residents accommodated the troops stationed at the base in a variety of ways.[47] Bradenton merged with nearby Manatee (incorporated in 1888) in 1943. Manatee faced similar financial problems as Bradenton did in regards to their bonds and faced high debt levels as a result but Manatee could not pay off the bonds.[41][48]

Second half of the 20th century

[edit]Mayor A. Sterling Hall took office in January 1948. During his tenure lasting the next 20 years before retiring, the city was radically transformed. While serving as mayor he was considered progressive in his time period when it came to racial issues. As mayor, he created a municipal housing authority and also do slum clearance. He created quality housing for black residents along with paving streets, bringing sewage service, water, and expanded garbage collection services to black neighborhoods.[49] Despite Mayor Hall's racial progressiveness, a Ku Klux Klan march occurred during his tenure in 1958 between Palmetto and Bradenton. The reason for the march was in response to a black group asking the county school board to either give them a new school building in Bradenton or integrate junior and senior high schools in the county.[50] The Manavista Hotel was demolished in 1959 and replaced with a motel and later a retirement community.[51] During the 1960s the Manatee River was dredged, and an area nicknamed "the Sandpile" was formed getting developed over the course of the rest of the 20th century and the 21st century.[43] During the Civil Rights Movement, Mayor Hall tried to make desegregation come about in his city in a nonviolent manner. Lunch counters were desegregated sometime during 1960[52] and a biracial commission was created during the summer of 1963.[53]

Bradenton built a new city hall located on 15th Street West bordering Wares Creek in January 1970 as a replacement to their location on 13th Street West, which the city had used since 1913.[54][55] Governor Claude R. Kirk Jr. arrived in Bradenton on April 6, 1970, in an attempt to stop Manatee County School District's desegregation busing. When he arrived he suspended the district superintendent along with the school district, leading to the district stopping the busing of 2,500 students and 107 teachers. During February he threatened to impeach a federal judge and said he would not sign checks that would pay for busing students. He stayed in the Manatee County School District's Administration building then located at the corner of 9th Avenue and 14th Street[56] for a week before being threatened with a $10,000 fine per day if he continued to stay in the building and was unsuccessful with preventing bussing.[57] The 8-floor Hotel Dixie Grande, which opened in April 1926, was demolished in August 1974.[58]

The Green Bridge was replaced in 1986.[43] The city hall moved to a new location on 12th Street West in November 1998 after the property was sold to a local resident with the intention of redeveloping it but plans never materialized.[54]

21st century

[edit]The local resident who had owned the former city hall property along Wares Creek sold it to a development group sometime in 2004, and it was demolished in December 2004.[54] The Bradenton Riverwalk, a 1.5-mile long park along the Manatee River opened in October 2012.[59] McKechnie Field, the spring training stadium for the Pittsburgh Pirates, was renamed LECOM Park in February 2017.[60]

Historic properties

[edit]Historic properties in Bradenton include:

- Bradenton Bank and Trust Company Building, 1925, now the Professional Building, 1023 Manatee Avenue, West

- Bradenton Carnegie Library, 1405 Fourth Avenue West

- Braden Castle Park Historic District, off Manatee Avenue and 27th St East

- Iron Block Building, 1896, 530 12th Street West (Old Main Street)

- Manatee County Courthouse, 1913, 1115 Manatee Avenue, West

- Old Manatee County Courthouse, 1860, 1404 Manatee Avenue, East

- Peninsular Telephone Company Building, 1925, 1009 4th Avenue, West

Geography

[edit]The approximate coordinates for the City of Bradenton is located at 27°29′N 82°35′W / 27.483°N 82.583°W.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Bradenton has a total area of 14.44 square miles (37.4 km2), of which 12.11 square miles (31.4 km2) is land and 2.33 square miles (6.0 km2) (16.14%) is water.

Bradenton is located on US 41 between Tampa and Sarasota. The area is surrounded by waterways, both fresh and saltwater. Along the Gulf of Mexico and into Tampa Bay are over 20 miles (32 km) of Florida beaches, many of which are shaded by Australian pines. Bordered on the north by the Manatee River, Bradenton is located on the mainland and is separated from the outer barrier islands of Anna Maria Island and Longboat Key by the Intracoastal Waterway.

Downtown Bradenton is located in the northwest area of the city. Home to many of Bradenton's offices and government buildings, the tallest is the Bradenton Financial Center, 12 stories high, with its blue-green windows. The next tallest is the brand new Manatee County Judicial Center with nine floors, located next to the historic courthouse. Other major downtown buildings include the Manatee County Government building and the headquarters of the School Board of Manatee County.

Climate

[edit]Bradenton has a typical Central Florida humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) characterized by hot, humid summers and warm winters. Bradenton borders a tropical climate, with only one month (January) having a mean temperature below 64 °F (18 °C), which is the threshold for a tropical climate.

| Climate data for Bradenton, Florida, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1911–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 91 (33) |

88 (31) |

91 (33) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

100 (38) |

100 (38) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

96 (36) |

91 (33) |

89 (32) |

101 (38) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 82.8 (28.2) |

84.1 (28.9) |

86.1 (30.1) |

89.9 (32.2) |

93.4 (34.1) |

95.7 (35.4) |

95.8 (35.4) |

95.3 (35.2) |

94.0 (34.4) |

91.0 (32.8) |

86.6 (30.3) |

83.4 (28.6) |

96.6 (35.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 72.0 (22.2) |

75.0 (23.9) |

78.4 (25.8) |

83.0 (28.3) |

88.2 (31.2) |

91.1 (32.8) |

92.0 (33.3) |

91.8 (33.2) |

90.0 (32.2) |

85.2 (29.6) |

78.6 (25.9) |

74.0 (23.3) |

83.3 (28.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 62.1 (16.7) |

64.9 (18.3) |

68.4 (20.2) |

73.0 (22.8) |

78.4 (25.8) |

82.4 (28.0) |

83.6 (28.7) |

83.7 (28.7) |

82.1 (27.8) |

76.7 (24.8) |

69.3 (20.7) |

64.5 (18.1) |

74.1 (23.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 52.2 (11.2) |

54.8 (12.7) |

58.4 (14.7) |

63.0 (17.2) |

68.5 (20.3) |

73.7 (23.2) |

75.2 (24.0) |

75.5 (24.2) |

74.2 (23.4) |

68.3 (20.2) |

60.1 (15.6) |

55.0 (12.8) |

64.9 (18.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 34.3 (1.3) |

38.0 (3.3) |

42.8 (6.0) |

49.5 (9.7) |

58.8 (14.9) |

68.4 (20.2) |

70.1 (21.2) |

71.4 (21.9) |

67.7 (19.8) |

54.9 (12.7) |

44.9 (7.2) |

38.5 (3.6) |

32.8 (0.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 23 (−5) |

21 (−6) |

30 (−1) |

38 (3) |

46 (8) |

52 (11) |

62 (17) |

60 (16) |

58 (14) |

40 (4) |

27 (−3) |

20 (−7) |

20 (−7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.76 (70) |

1.99 (51) |

3.11 (79) |

2.53 (64) |

3.49 (89) |

9.03 (229) |

8.91 (226) |

10.07 (256) |

7.43 (189) |

2.88 (73) |

1.82 (46) |

2.26 (57) |

56.28 (1,430) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.5 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 6.9 | 14.0 | 17.2 | 18.1 | 14.1 | 7.5 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 113.6 |

| Source: NOAA[61][62] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 1,886 | — | |

| 1920 | 3,868 | 105.1% | |

| 1930 | 5,986 | 54.8% | |

| 1940 | 7,444 | 24.4% | |

| 1950 | 13,604 | 82.8% | |

| 1960 | 19,380 | 42.5% | |

| 1970 | 21,040 | 8.6% | |

| 1980 | 30,228 | 43.7% | |

| 1990 | 43,779 | 44.8% | |

| 2000 | 49,504 | 13.1% | |

| 2010 | 49,546 | 0.1% | |

| 2020 | 55,698 | 12.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[63] | |||

Bradenton is a principal city of the North Port–Sarasota–Bradenton metropolitan statistical area, which had a population of 833,716 as of 2020.[64]

2010 and 2020 census

[edit]| Race | Pop 2010[65] | Pop 2020[66] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 31,918 | 33,568 | 64.42% | 60.27% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 7,693 | 7,840 | 15.53% | 14.08% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 84 | 110 | 0.17% | 0.20% |

| Asian (NH) | 523 | 773 | 1.06% | 1.39% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (NH) | 30 | 53 | 0.06% | 0.10% |

| Some other race (NH) | 85 | 242 | 0.17% | 0.43% |

| Two or more races/Multiracial (NH) | 789 | 1,883 | 1.59% | 3.38% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 8,424 | 11,229 | 17.00% | 20.16% |

| Total | 49,546 | 55,698 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 55,698 people, 22,350 households, and 13,033 families residing in the city.[67]

As of the 2010 United States census, there were 49,546 people, 21,120 households, and 12,341 families residing in the city.[68]

2000 census

[edit]As of the census[6] of 2000, there were 49,504 people, 21,379 households, and 12,720 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,088.5 inhabitants per square mile (1,578.6/km2). There were 24,887 housing units at an average density of 2,055.4 per square mile (793.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 78.14% White, 15.11% African American, 0.79% Asian, 0.29% Native American, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 3.91% from other races, and 1.71% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 11.26% of the population.

In 2000, there were 21,379 households, out of which 23.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.5% were married couples living together, 12.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.5% were non-families. 34.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 17.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.24 and the average family size was 2.85.

In 2000, in the city 21.6% of the population was under the age of 18, 7.7% from 18 to 24, 25.3% from 25 to 44, 19.9% from 45 to 64, and 25.4% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.9 males.

In 2000, the median income for a household in the city was $34,902, and the median income for a family was $42,366. Males had a median income of $28,262 versus $23,292 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,133. About 9.7% of families and 13.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.3% of those under age 18 and 8.2% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

[edit]Tropicana Products was founded in Bradenton in 1947 by Anthony T. Rossi, an Italian immigrant. By 2004 it had over 8,000 employees and marketed its products throughout the United States. PepsiCo, Inc., acquired it in 1998. Tropicana's Juice Trains have been running to northern markets via CSX and predecessor railroads since 1971. In 2003, Pepsi relocated Tropicana's corporate headquarters to Chicago after it acquired Gatorade and consolidated its non-carbonated beverage businesses. However, their juice production facilities remain in Bradenton.[69]

Champs Sports, a nationwide sports apparel chain, is headquartered in Bradenton.[70] The department store chain Bealls is also headquartered in Bradenton.[71]

Bradenton was significantly affected by the United States housing market correction, as reported by CNN, projecting a 24.8% loss in median home values by the third quarter of 2008.[72] Real estate has shown a recovery since 2012, as home prices stabilize and inventory subsides.[citation needed]

Transportation

[edit]

Bradenton is served by Sarasota-Bradenton International Airport and is connected to St. Petersburg by the Sunshine Skyway Bridge. The Sunshine Skyway is a 5.5-mile (8.9 km) cross-bay bridge that rises 250 feet (76 m) above the bay at its highest point. Remnants of the old Skyway bridge have been converted into a fishing pier extending into Tampa Bay from both sides of the bay.

Manatee County Area Transit (MCAT) buses serve Bradenton along with the cities/communities of Palmetto, Ellenton, Anna Maria, Holmes Beach, Bradenton Beach, Longboat Key, Tallevast and Samoset, with transfers to Sarasota and St. Petersburg. Free trolleys run north–south on Anna Maria Island, as well as to/from various points on the mainland. Amtrak charter buses run through downtown Bradenton outside the courthouse to Tampa Union Station and Venice.

Government

[edit]The city is governed by a city council with five members. Each of the members are residents of one of the five wards. The city council selects the city's vice mayor. The mayor and the five city council members are elected at-large for a four-year term. In Bradenton, the mayor functions as the head of the council and presides at meetings making a tie-breaking vote. The city council has the ability to elect a vice mayor. A vice mayor has the ability to take over when the mayor either resigns, dies or takes a leave of absence.[73]

Media

[edit]Newspapers

[edit]- The Bradenton Herald is Manatee County's local newspaper, published daily.

- The Bradenton Times is Manatee County's local online-only newspaper.

- Bradenton Patch is Bradenton's local online-only paper.

- Daily editions of the Sarasota Herald Tribune and the Tampa Bay Times are also available throughout the area.

Radio stations

[edit]Bradenton is located in the Sarasota-Bradenton radio market. It also receives many stations from the nearby Tampa-St. Petersburg market.

The stations listed below are located and/or licensed in Bradenton or Manatee County:

- WWPR – 1490 AM – studio and transmitter in Bradenton

- WBRD – 1420 AM – licensed to Palmetto

- WJIS – 88.1 FM

- WPBB – 98.7 FM (studios and transmitter in Pinellas County)

- WHPT – 102.5 FM (Sarasota; transmitter in northeastern corner of Sarasota County; studios in St. Petersburg)

- WRUB – 106.5 FM

Television stations

[edit]WSNN-LD is based in Sarasota but transmits from Manatee County. WWSB channel 40, the local ABC affiliate, is based in Sarasota, but has a transmitter in Parrish, northeast of Bradenton; it is seen on cable channel 7 on most cable systems in the area. WXPX-TV channel 66, the local Ion Television affiliate, is licensed in Bradenton, with its transmitter in Riverview in Hillsborough County.

Education

[edit]Manatee County Public Schools operates area public schools. Schools in the city limits include:

The State College of Florida, Manatee-Sarasota's (SCF) main campus is located in Bayshore Gardens, and State College of Florida Collegiate School has a campus on the SCF Bradenton campus.[74][75]

Culture

[edit]Bradenton is home to the Washington Park neighborhood, a historically African American Community where Lincoln Academy was located.[76][77]

Bradenton is home to the Village of the Arts, a renovated neighborhood immediately south of downtown where special zoning laws allow residents to live and work in their homes. Many of these once dilapidated houses have been converted into studios, galleries, small restaurants and other small businesses. The Village of the Arts promotes its 'First Fridays' activities celebrating the seasons and different holidays. The Village of the Arts remains the largest arts district on the Gulf Coast.

The Manatee Players, who reside at the Manatee Performing Arts Center, have a three-year record of first-place wins within the Florida Theatre Conference and the Southeastern Theatre Conference competitions. In addition, the theatre currently holds the first place title from the American Association of Community Theatre competition.

Located on the Manatee River in downtown Bradenton is the South Florida Museum, Bishop Planetarium and Parker Manatee Aquarium. This one-stop museum-planetarium-aquarium offers a glimpse of Florida history, a star and multimedia show, and ongoing lecture and film series. The Parker Manatee Aquarium was the permanent home to Manatee County's most famous resident and official mascot, Snooty, the manatee. Born at the Miami Aquarium and Tackle Company on July 21, 1948, Snooty was one of the first recorded captive manatee births. He was the oldest manatee in captivity, and likely the oldest manatee in the world.[78] On July 23, 2017, two days after his 69th birthday, Snooty died as the result of drowning.[79]

ArtCenter Manatee is the center for art and art education in Manatee County. The nearly 10,000 sq ft (930 m2) building in downtown Bradenton features three galleries, five classrooms, an Artists' Market gift shop and an art library featuring over 3,000 art volumes.

The nonprofit organization Realize Bradenton works with the above-listed cultural partners to promote Downtown Bradenton as a destination for the arts. It also produces events in the downtown area with a focus on arts and culture.[80]

Additionally, the town is the subject of the We the Kings song "This Is Our Town"; they, as well as the band Have Gun, Will Travel originate from Bradenton.

Sports

[edit]Bradenton is the spring training home of Major League Baseball's Pittsburgh Pirates who play their home games at downtown's LECOM Park. During the regular baseball season, the stadium is home to the minor league Bradenton Marauders who play in the Florida State League in Class A-Advanced.

The city is home to the State College of Florida, Manatee–Sarasota Manatees sports teams.

Manatee County high schools produce several teams including Manatee High School whose football team was nationally ranked in the 1950s, 1980s, and 1990s and regained their national status in 2009. Manatee High School has won five football state championships. Bradenton is also home to the IMG Academy, the home of the U.S U-17 residential soccer program.

The Concession Golf Club in Bradenton was home of the 2015 NCAA Division I Men's Golf Championship.

Bradenton and Sarasota together held the 2021 U-18 Baseball World Cup.[81]

Points of interest

[edit]- Bishop Museum of Science and Nature, home of the late manatee Snooty

- Bradenton Riverwalk

- De Soto National Memorial

- DeSoto Square (Now abandoned and vacant)

- Manatee Village Historical Park

- Neal Preserve

- Pittsburgh Pirates spring training at LECOM Park

- Robinson Preserve[82]

- Village of the Arts

Notable people

[edit]- Hank Aaron (1934–2021) – Major League Baseball (MLB) player and National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum inductee[83]

- Freddy Adu (b. 1989) – soccer player[84]

- Hugo Armando (b. 1978) – tennis player[85]

- Sekou Bangoura (b. 1991) – tennis player[86]

- Bob Barron (1928–1991) – NASCAR Cup Series driver[87]

- Waite Bellamy (b. 1940) – Eastern Professional Basketball League player[88]

- Chase Brown (b. 2000) – National Football League (NFL) player[89]

- Sydney Brown (b. 2000) – NFL player[89]

- Jim Boyd (b. 1956) – Florida Senate Majority Leader[90]

- An Byeong-hun (b. 1991) – PGA Tour golfer[91]

- Sandra Cacic (b. 1974) – tennis player[92]

- Gene Clines (1946–2022) – MLB player[93]

- Kimberly Couts (b. 1989) – tennis player[94]

- Jordan Cox (b. 1992) – tennis player[95]

- Ed Culpepper (1934–2021) – NFL player[96]

- Tiffany Dabek (b. 1990) – tennis player and coach[97]

- Taylor Dent (b. 1981) – tennis player[98]

- Bill Doak (1891–1954) – MLB player[99]

- Eric DuBose (b. 1975) – MLB player[100]

- Brian Dunn (b. 1974) – tennis player[101]

- Victoria Duval (b. 1995) – tennis player[102]

- Tyler Dyson (b. 1997) – MLB player[103]

- Zach Edey (b. 2002) – National Basketball Association (NBA) player[104]

- Graeme Edge (1941–2021) – co-founder of The Moody Blues, drummer, songwriter, and poet[105]

- Alfred Ellis (1941–2021) – member of the The J.B.'s, saxophonist, composer, and arranger[106]

- Deshaun Fenwick (b. 1991) – NFL player[107]

- Tommie Frazier (b. 1974) – Canadian Football League player and college football coach[108]

- Colton Gordon (b. 1998) – MLB player

- Sammy Green (b. 1954) – NFL player[109]

- Rod Harper (b. 1985) – NFL player[110]

- Christian Harrison (b. 1994) – tennis player[111]

- Teri Harrison (b. 1981) – model, actress, and Playboy Playmate[112]

- Jamea Jackson (b. 1986) – tennis player[113]

- Helen Jepson (1904–1997) – opera singer[114]

- Hank Johnson (1906–1982) – MLB player[115]

- Shang Juncheng (b. 2005) – tennis player[116]

- Al Klink (1915–1991) – saxophonist[117]

- Jessica Korda (b. 1993) – LPGA Tour golfer[118]

- Nelly Korda (b. 1998) – LPGA Tour golfer[118]

- Sebastian Korda (b. 2000) – tennis player[119]

- Michaëlla Krajicek (b. 1989) – tennis player[120]

- Rick Lamb (b. 1990) – PGA Tour golfer[121]

- JC Latham (b. 2003) – NFL player[122]

- Kelvin McKnight (b. 1997) – NFL player[123]

- Adrian McPherson (b. 1983) – NFL player[124]

- Ahmad Miller (b. 1978) – NFL player[125]

- Shintaro Mochizuki (b. 2003) – tennis player[126]

- Johnny Moore (1902–1991) – MLB player[127]

- Jamie Moyer (b. 1962) – MLB player[128]

- Naoki Nakagawa (b. 1996) – tennis player[129]

- Sharrod Neasman (b. 1991) – NFL player[130]

- Ingrid Neel (b. 1998) – tennis player[131]

- Ryan Neuzil (b. 1997) – NFL player[132]

- Whitney Osuigwe (b. 2002) – tennis player[133]

- Brian Poole (b. 1992) – NFL player[130]

- Maria Sharapova (b. 1987) – tennis player[134]

- Satnam Singh (b. 1995) – NBA player and wrestler[135]

- Myles Straw (b. 1994) – MLB player[136]

- Sunitha Rao (b. 1985) – tennis player[137]

- John Reeves (b. 1975) – NFL player[138]

- Austin Reiter (b. 1991) – NFL player[139]

- Patrik Rikl (b. 1999) – tennis player[140]

- Anthony Rossi (1900–1993) – businessman and founder of Tropicana[141]

- Clifford Rozier (1972–2018) – NBA player[142]

- Ace Sanders (b. 1991) – NFL player[143]

- Robby Stevenson (b. 1976) – NFL player[144]

- Willie Taggart (b. 1976) – NFL player and coach[145]

- Sarah Taylor (b. 1981) – tennis player[146]

- Charles Trippy (b. 1984) – bassist for We the Kings and YouTuber[147]

- Peter Warrick (b. 1997) – NFL player[148]

- Fabian Washington (b. 1983) – NFL player[149]

- Benny Williams (b. 2002) – college basketball player[150]

- Todd Williams (b. 1978) – NFL player[151]

- Tyrone Williams (b. 1973) – NFL player[152]

- Sam Woolf (b. 1996) – singer-songwriter[153]

References

[edit]- ^ "Welcome to the Friendly City!". City of Bradenton. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Favorite, Merab-Michal (2013). Bradenton. Arcadia Publishing. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7385-9078-3. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Hall, A. Sterling (1970). Speech by A. Sterling Hall "Bradenton Municipal Government". p. 2.

- ^ "Mayor & Council". City of Bradenton. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Bradenton". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. October 19, 1979. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ White, Dale (September 8, 2016). "When Bradenton was a home for escaped slaves". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ Eger, Issac (June 27, 2018). "A Newly Excavated Settlement Highlights Florida's History as a Haven for Escaped Slaves". Sarasota Magazine. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ Congress, United States (1860). "Land Claims in East Florida". American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States ... Gales and Seaton.

- ^ Favorite, Merab (November 12, 2017). "Sunday Favorites: The First Settler". The Bradenton Times. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ King, Carl (April 19, 1972). "Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. pp. 6–7. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ a b King, Carl (1979–1982). "Speech by Carl King "The Plantation Builders"". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ King, Carl (March 26, 1983). "Speech by Carl King "Boat Tour on Anna Maria Sound and Manatee River"". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Knetsch, Joe (2003). Florida's Seminole wars, 1817-1858. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub. p. 153. ISBN 9781589730786.

- ^ "Major Adams' Castle, Bradentown". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Favorite, Merab-Michal (January 8, 2012). "Community Sunday Favorites: Villa Zanza and the Eccentric Major Adams". The Bradenton Times. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "Gladys Turner Pittman with Bradenton's First Post Office Marker" (JPEG). Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection (Photograph). 1983. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ Turner, Mrs. William Jr. (October 15, 1975). "Speech by Mrs. William S. Turner, Jr. "Major William I. Turner"". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. p. 7. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ a b King, Carl (May 17, 1978). "Speech by Carl King "The Story of Bradenton". Manatee County Public Library Digital Collection. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ "Residences on Wares Creek, Bradentown". Manatee County Public Library System Digital Collection. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ "Manatee County Courthouse from the 1890s". Manatee County Public Library Digital Collection. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ a b "Manatee County Court House, Bradentown". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. 1896–1907. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Gibson, Pamela (February 1985). "Speech by Pamela Gibson "Railroads of Manatee County"". Manatee County Public Library Digital Collection. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ Parvin, Elizabeth (May 15, 1970). "Early Cultural and Social Life of Manatee County". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Sharyn (October 24, 1983). "1903 Banner Year for Bradentown". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Porter, M. (2014). Manatee history matters. Bradenton Herald. Retrieved from https://www.bradenton.com/news/local/article34739931.html

- ^ Grimes, David (November 23, 1979). "The Legends Behind Manatee Names". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. pp. 1B. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ Poston, Wayne (January 15, 2003). "Speech by Wayne Poston "Past and Future of Bradenton"". Manatee County Public Library System Digital Collection. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Thompson, Sharyn (October 24, 1983). "1903 Banner Year for Bradentown". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Slusser, Cathy (March 21, 2001). "Speech by Cathy Slusser "Manatee County History"". Manatee County Public Library System Digital Collection. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ a b Lambert, Joe (January 21, 1987). "Speech by Joe Lambert "The Graham-Davis House"". Manatee County Public Library System Digital Collection. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ Poston, Wayne (January 15, 2003). "Speech by Wayne Poston "Past and Future of Bradenton"". Manatee County Public Library System – Digital Collection. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ "Manatee County Courthouse". Manatee County Public Library System – Digital Collection. 1900s. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Russell, Cindy (November 18, 2014). "Manatee History Matters: The Manavista Hotel was Bradenton's first 'sky scraper'". The Bradenton Herald. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ a b "Davis Bridge over Manatee River". Manatee County Digital Library System: Digital Collection (Postcard). 1910. Archived from the original on May 27, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c Gibson, Pamela (1985). "Speech by Pamela Gibson "Some Early Bridges of Manatee County, North to South, East to West"". Manatee County Public Library Collection: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on May 27, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ "Postcard of Prospect Avenue Looking North from Manatee Avenue, Bradentown". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. 1914. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ King, Carl (May 17, 1978). "Speech by Carl King "Real Estate Trends in Manatee County"". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Hall, A. Sterling (November 18, 1970). "Speech by A. Sterling Hall "Bradenton Municipal Government"". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ Kropp Co, E.C. (1935). "Municipal Pier, Bradenton". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection (Postcard). Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c Co., Gulfstream Card (2002–2010). "Bradenton, Florida". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection (Postcard). Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Sales Co., Hartman Litho (1947). "U.S. Post Office, Bradenton". County Public Library System: Digital Collection (Postcard). Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1947). Florida: A Guide to the Southernmost State (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 394. ISBN 9781595342089.

- ^ Warren, G. "Speech by Lt.Col. G. Warren Johnson Jr "World War II Comes to Manatee County"". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ Favorite, Merab (March 3, 2019). "Sunday Favorites: Camp Weatherford". The Bradenton Times. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ Mannix, Vin (June 17, 2007). "The founding of the Manatee settlement". Bradenton Herald. Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ Roundtree, Craig (November 18, 1991). "Speech by Craig Roundtree "Mayors of the City of Bradenton, Past and Present"". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Marth, Del (March 9, 1958). "KKK rally in Bradenton, rides through quarters, police and sheriff disagree". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "The Manavista Hotel, Bradenton". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Archives. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ the Student Voice (August 1960). "STATE REPORTS – FLORIDA" (PDF). the Student Voice. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ https://www.crmvet.org/docs/6312_src_crsummary.pdf Southern Regional Council , Inc. - "CIVIL RIGHTS: YEAR-END Summary", Dec 31, 1963

- ^ a b c Card Distributors, West Coast (1971–1978). "Bradenton City Hall". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection (Postcard). Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Pharmacy, Thomas' (1913–1917). "City Hall and Fire Station, Bradentown". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection (Postcard). Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ "Manatee County High School". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "Protest march during Governor Kirk's busing Crisis". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ Co., Asheville postcard (1934–1941). "Seasons Best Greeting, Hotel Dixie Grande". Manatee County Public Library System: Digital Collection (Postcard). Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Hice, Sandra (October 16, 2012). "New Bradenton Riverwalk Revives City's Sense Of Place". 83 degrees. Issue Media Group. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ "Pirates' spring training home renamed LECOM Park". USA Today. February 10, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2010-2020; Subcounty Resident Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019; April 1, 2020; and July 1, 2020 (SUB-EST2020)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Bradenton city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Bradenton city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2020: Bradenton city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2010: Bradenton city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ Ferguson, Grier (March 22, 2019). "Look inside Tropicana plant in Bradenton reveals manufacturing operation with precise processes, staggering numbers". Business Observer. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Staff (June 17, 2010). "Business owner grew large coaching". Business Observer. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Our History". Beall's, Inc. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Christie, Les (May 6, 2011). "Double-digit home price drops coming". CNN. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- ^ "City of Bradenton Charter" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ "Locations". State College of Florida, Manatee–Sarasota. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

SCF Bradenton 5840 26th St. W., Bradenton, FL 34207

– Campus map here, which indicates the exact location of SCFCS. - ^ "2010 CENSUS – CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Bayshore Gardens CDP, FL" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ "CONTENTdm".

- ^ "Lincoln High School Historical Marker".

- ^ Snooty the Manatee. South Florida Museum. ISBN 978-1-56944-441-2.

- ^ Mettler, Katie (July 24, 2017). "Snooty the famous manatee dies in 'heartbreaking accident' days after his 69th birthday". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ January Holmes and Carl Mario Nudi, "Realizing Bradenton's culture potential", Bradenton Herald, May 14, 2010

- ^ "Press Conference: "The XXX WBSC U-18 Baseball World Cup will be blessed by Florida hospitality"". WBSC. World Baseball Softball Confederation (WBSC). Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ "Robinson Preserve". Manatee County Government. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Chris (March 11, 2019). "When Hank Aaron lived in a segregated Bradenton". The St. Augustine Record. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ "SI.com – Sports Illustrated – The Magazine – Who's Next? Freddy Adu". Sports Illustrated. March 7, 2003. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ^ "USTA Player Development Hires Former Top 100 Player Hugo Armando as USTA Coach". TennisIndustryMag. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Sekou Bangoura". ATP Tour. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Robert Frank Barron in the Florida, U.S., Death Index, 1877–1998

- ^ "Waite Bellamy". NASL Jerseys. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ a b Baker, Matt (October 22, 2022). "How 2 Manatee County families helped the nation's top rusher reach stardom". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Jim Boyd". Florida Senate. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Kennedy, Sara (August 31, 2009). "A win for the ages". The Bradenton Herald. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ McKibben, Dave (September 29, 1997). "Cacic Glad She Extended Her Stay in U.S." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Gene Clines, part of 1st MLB all-minority lineup, dies at 75". Associated Press. January 27, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Huber, Mic (April 13, 2011). "Larcher de Brito beats training partner". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Polen, Richard (July 22, 2014). "Wimbledon juniors runner-up adjusting to pro tournaments". The Joplin Globe. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Ed Culpepper". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Huber, Mic (September 4, 2009). "This 'Hit Man' from Moscow is unbeatable ... and only 9". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Huber, Mic (March 30, 2010). "Bradenton's Dent in Sarasota Open". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Steinberg, Steve. "Bill Doak". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Eric DuBose". Major League Baseball. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Jones, Terry (October 17, 2005). "Dunn heads for Canada to wrap up successful summer". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Fendrich, Howard (August 28, 2012). "Bubbly Bradenton teen enjoys night with Clijsters at Open". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Tyler Dyson's Braden River High School Career". MaxPreps. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ Dopirak, Dustin (November 14, 2019). "'It seems like a movie': Purdue's new big man Zach Edey was on skates until two years ago". The Athletic. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ Runnells, Charles (February 19, 2020). "Moody Blues' John Lodge talks hometown show, new album, saluting Ray Thomas, Naples condo". Naples Daily News. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ "Pee Wee Ellis Concert & Tour History". Concert Archives. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Wilson, David (May 4, 2017). "Braden River's Deshaun Fenwick discusses commitment to South Carolina". The Bradenton Herald. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ "Randy York's N-Sider: Tommie Frazier – Huskers.com – Nebraska Athletics Official Web Site". huskers.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ^ "Sammy Green". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Perkins, Pete (April 11, 2009). "Siegfried reaches out, finds talented WR". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Brockman, Jim (April 12, 2022). "Bradenton's Christian Harrison hopes to make a run at Sarasota Open". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Teri Marie Harrison Playboy". Playboy. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Tignor, Steve (May 24, 2023). "Holding Court with...Jamea Jackson". Tennis.com. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Oliver, Myrna (September 20, 1997). "Helen Jepson; Opera Star of '30s and '40s". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Nowlin, Bill. "Hank Johnson". sabr.org. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Juncheng Shang". DB4Tennis. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Al Klink; Big-Band Saxophone Player". Los Angeles Times. March 21, 1991. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ a b "This Bradenton Family Has a Tennis Star and Two Olympic-Bound Golfers". Sarasotamagazine.com. July 21, 2021.

- ^ "Sebastian Korda", Wikipedia, August 10, 2023, retrieved August 13, 2023

- ^ "Michaella Krajicek". Women's Tennis Association. Archived from the original on October 1, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Rick Lamb – Official PGA TOUR Profile". PGA Tour. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ Hogg, Curt (January 26, 2019). "Five-star DE sophomore JC Latham transferring to IMG Academy". USA Today. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "Kelvin McKnight". Samford University. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Young, Pete (June 20, 2006). "STRENGTH VS. STRENGTH // Remember the name Adrian McPherson". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on January 15, 2024. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Ahmad Miller". ESPN. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "SHINTARO MOCHIZUKI OF IMG ACADEMY WINS 2019 WIMBLEDON BOYS' SINGLES TITLE". IMG Academy. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Rogers III, C. Paul. "Johnny Moore". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Sheridan, Phil (March 13, 2011). "Phil Sheridan: Moyer eyes 2012 comeback". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on March 18, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ^ "Naoka Nakagawa stays aggressive, wins USTA Internationals". Daily Breeze. April 8, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Dill, Jason (February 8, 2017). "Hometown Heroes Brian Poole and Sharrod Neasman deserve cheers for reaching the Super Bowl". The Bradenton Herald. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Pratt, Steve (September 10, 2015). "Tennis: Neel, partner eliminated at U.S. Open Junior". Post-Bulletin. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Ryan Neuzil's Braden River High School Career". MaxPreps. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ Marshall, Ashley (February 19, 2019). "BLACK HISTORY MONTH: WHITNEY OSUIGWE". United States Tennis Association. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "ESPN.com: TENNIS – IMG factory churns out talent". ESPN. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- ^ Winegardner, Mark (December 27, 2011). "The Mavericks' Satnam Singh becomes NBA's first Indian-born player". ESPN. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "Myles Straw Class of 2013". Perfect Game. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ "Sharapova, Taylor, Rao having summer success". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. August 8, 2003. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "John Reeves Biography". ESPN. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Austin Reiter". USF Athletics. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Patrik Rikl". Stevegtennis.com. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Basse, Craig (January 26, 1993). "Anthony Rossi, founder of Tropicana, dead at 92". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Anderson, Chris (July 19, 2018). ""The final shot of Clifford's life is good"". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Ace Sanders". ESPN. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Pentz, Perry D. (July 17, 2007). "Robby Stevenson played in 2 NCAA national championship games". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Newberg, Josh (August 22, 2018). "Willie Taggart takes us on a tour of his old neighborhood". 247Sports. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Huber, Mic (December 10, 2002). "Smashnova, Taylor among early entrants". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "ABOUT CHARLES". Charles Trippy. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Player Bio: Peter Warrick". Seminoles. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ^ "Fabian Washington Interview". Baltimore Beatdown. May 13, 2009. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Waters, Mike (August 12, 2020). "How coronavirus concerns played a role in Syracuse basketball commit Benny Williams' transfer to IMG Academy". Syracuse.com. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "EX-FSU, Southeast High star Todd Williams dead at 35". Bay News 9. January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Scarella, Michael (April 19, 2007). "Former NFL player going to jail for battery on a Manatee County deputy". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Handelman, Jay (January 15, 2014). "Bradenton student Sam Woolf advances to Hollywood Week on 'American Idol'". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved January 7, 2024.