Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting

Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting represents the 16th-century response to Italian Renaissance art in the Low Countries, as well as many continuities with the preceding Early Netherlandish painting. The period spans from the Antwerp Mannerists and Hieronymus Bosch at the start of the 16th century to the late Northern Mannerists such as Hendrik Goltzius and Joachim Wtewael at the end. Artists drew on both the recent innovations of Italian painting and the local traditions of the Early Netherlandish artists.

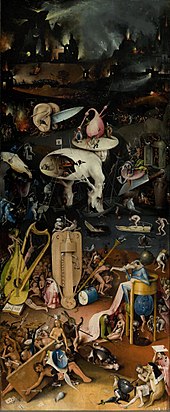

Antwerp was the most important artistic centre in the region. Many artists worked for European courts, including Bosch, whose fantastic painted images left a long legacy. Jan Mabuse, Maarten van Heemskerck and Frans Floris were all instrumental in adopting Italian models and incorporating them into their own artistic language. Pieter Brueghel the Elder, with Bosch the only artist from the period to remain widely familiar, may seem atypical, but in fact his many innovations drew on the fertile artistic scene in Antwerp.

Dutch and Flemish painters were also instrumental in establishing new subjects such as landscape painting and genre painting. Joachim Patinir, for example, played an important role in developing landscape painting, inventing the compositional type of the world landscape, which was perfected by Pieter Bruegel the Elder who, followed by Pieter Aertsen, also helped popularise genre painting. From the mid-century Pieter Aertsen, later followed by his nephew Joachim Beuckelaer, established a type of "monumental still life" featuring large spreads of food with genre figures, and in the background small religious of moral scenes. Like the world landscapes, these represented a typically "Mannerist inversion" of the normal decorum of the hierarchy of genres, giving the "lower" subject matter more space than the "higher".[1] Anthonis Mor was the leading portraitist of the mid-century, in demand in courts all over Europe for his reliable portraits in a style that combined Netherlandish precision with the lessons of Titian and other Italian painters.

Stylistic evolution

[edit]Italian Renaissance influences begin to show on Early Netherlandish painting around 1500, but in many ways the older style was remarkably persistent. Antwerp Mannerism is a term for painters showing some Italian influence, but mainly continuing the style and subjects of the older masters. Hieronymus Bosch is a highly individual artist, whose work is strange and full of seemingly irrational imagery, making it difficult to interpret.[2] Most of all it seems surprisingly modern, introducing a world of dreams that seems more related to Gothic art than the Italian Renaissance, although some Venetian prints of the same period show a comparable degree of fantasy. The Romanists were the next phase of influence, adopting Italian styles in a far more thorough way.

After 1550 the Flemish and Dutch painters begin to show more interest in nature and beauty "in itself", leading to a style that incorporates Renaissance elements, but remains far from the elegant lightness of Italian Renaissance art,[3] and directly leads to the themes of the great Flemish and Dutch Baroque painters: landscapes, still lifes and genre painting (scenes from everyday life).[2]

This evolution is seen in the works of Joachim Patinir and Pieter Aertsen, but the true genius among these painters was Pieter Brueghel the Elder, well known for his depictions of nature and everyday life, showing a preference for the natural condition of man, choosing to depict the peasant instead of the prince.

The Fall of Icarus (now in fact considered a copy of a Brueghel work), although highly atypical in many ways, combines several elements of Northern Renaissance painting. It hints at the renewed interest for antiquity (the Icarus legend), but the hero Icarus is hidden away in the background. The main actors in the painting are nature itself and, most prominently, the peasant, who does not even look up from his plough when Icarus falls. Brueghel shows man as an anti-hero, comical and sometimes grotesque.[3]

Painters

[edit]

- Pieter Aertsen

- Simon Bening

- Hieronymus Bosch

- Pieter Brueghel the Elder

- Pieter Brueghel the Younger

- Joachim Beuckelaer

- Joos van Cleve

- Pieter Coecke van Aelst

- Hieronymus Cock

- Corneille de Lyon

- Hans Eworth

- Frans Floris

- Maarten van Heemskerck

- Caterina van Hemessen

- Jan Sanders van Hemessen

- Adriaen Isenbrant

- Jan Mabuse van Gosaert

- Anthonis Mor

- Lucas van Leyden

- Lambert Lombard

- Quentin Matsys

- Jan Mostaert

- Bernard van Orley

- Joachim Patinir

- Frans Pourbus the Elder

- Pieter Pourbus

- Jan Provoost

- Marinus van Reymerswaele

- Jan van Scorel

- Levina Teerlinc

- Jacob van Utrecht

See also

[edit]| History of Dutch and Flemish painting |

|---|

| Periods |

|

| Lists |

Notes

[edit]- ^ Snyder, 409–412, 432–445

- ^ a b Janson, H.W.; Janson, Anthony F. (1997). History of Art (5th, rev. ed.). New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-3442-6.

- ^ a b Heughebaert, H.; Defoort, A.; Van Der Donck, R. (1998). Artistieke opvoeding. Wommelgem, Belgium: Den Gulden Engel bvba. ISBN 90-5035-222-7.

References

[edit]- Snyder, James. Northern Renaissance Art, 1985, Harry N. Abrams, ISBN 0-13-623596-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Orenstein, Nadine M., ed. (2001). Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Drawings and Prints. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-990-1.

External links

[edit] Media related to Northern Renaissance paintings at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Northern Renaissance paintings at Wikimedia Commons