Rumelihisarı

| Rumelihisarı | |

|---|---|

| Rumelihisarı, Istanbul, Turkey | |

| |

| Coordinates | 41°05′05″N 29°03′22″E / 41.084722°N 29.056111°E |

| Type | Fortress |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1452 |

| Built by | Mehmed II |

| Battles/wars | Conquest of Constantinople |

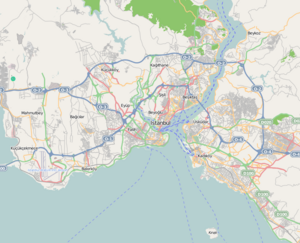

Rumelihisarı (also known as Rumelian Fortress and Roumeli Hissar Fortress[1]) or Boğazkesen Fortress (literally 'strait-cutter fortress') is a medieval Ottoman fortress located in Istanbul, Turkey, on a series of hills on the European banks of the Bosphorus. The fortress also lends its name to the immediate neighborhood around it in the city's Sarıyer district.

Conceived and built between 1451 and 1452 CE on the orders of Sultan Mehmed II, the complex was commissioned in preparation for a planned Ottoman siege on the then-Byzantine city of Constantinople,[1] with the goal of cutting off maritime military and logistical relief that could potentially come to the Byzantines' aid by way of the Bosphorus Strait, hence the fortress's alternative name, "Boğazkesen", i.e. "Strait-cutter" Castle. Its older sister structure, Anadoluhisari ("Anatolian Fortress"), sits on the opposite banks of the Bosporus, and the two fortresses worked in tandem during the final siege to throttle all naval traffic along the Bosphorus, thus helping the Ottomans achieve their goal of making the city of Constantinople (later renamed Istanbul) their new imperial capital in 1453.

After the Ottoman conquest of the city, Rumelihisarı served as a customs checkpoint and occasional prison, notably for the embassies of states that were at war with the Empire. After suffering extensive damage in the Great Earthquake of 1509, the structure was repaired, and was used continuously until the late 19th century.

Today, the fortress is a popular museum open to the public, and further acts as an open-air venue for seasonal concerts, art festivals, and special events.

History

[edit]Construction

[edit]

The necessity of a strategic fortress on the Bosphorus was well known to the Ottomans, who had started in the late 14th century to harbor intentions of capturing the city of Constantinople as a new capital for their then-nascent Empire. In a previous Ottoman attempt to conquer the city, Sultan Murad II (1421–44, 1446–51) had encountered difficulties due to a blockade of the Bosphorus by the Byzantine fleet. Having learned the importance of maritime strategy from this earlier attempt, Sultan Mehmed II (1444–46, 1451–81), son of Murad II, started planning a new offensive immediately following his ascent to the throne in 1451.

In response to the coronation of the ambitious young Sultan, Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI (1449–53), who understood Mehmed's intentions on Constantinople and was wary of the threat posed by the growing Ottoman influence in the region, hoped to secure a diplomatic solution that would protect the city, while averting the Byzantines' long-term decline.

Mehmed refused the offer of peace proffered, and proceeded with his siege plans by commissioning the construction of a large fortress that would be used to control all sea traffic along the Bosphorus, and would work together with the older Anadoluhisari (Anatolia Fortress) on the strait to prevent any possible maritime aid from reaching Constantinople during the final Ottoman siege of the city in 1453, particularly from Genoese colonies along the Black Sea, such as Caffa, Sinop and Amasra.

The site for the new fortress was quickly decided to be the narrowmost point of the Bosphorus, where the strait is a mere 660 meters (2,170 ft) wide. This tall, hilltop site on the strait's European banks not only made for easier control of the waterway, but also had the advantage of being situated directly across the Anadoluhisarı ("Anatolian Fortress") on the Anatolian (i.e. Asian) banks of the Bosphorus; an older Ottoman fortress built between 1393 and 1394 by Sultan Bayezid I. Historically, there had been a Roman fortification at the hilltop where Rumelihisari was to be built, which had later been used as a prison by the Byzantines and Genoese. Later on, a monastery had been built there.

Construction began on April 15, 1452. For good luck, ram's blood was mixed with the mortar for the first layer. Some have speculated the layout is a cabbalistic combination (Abjad numerals) of the initials of Mehmed and the Muhammad.[2] Each one of the three main towers was named after the royal vizier who supervised its respective construction; Sadrazam Çandarlı Halil Pasha, who built the large tower next to the gate; Zağanos Pasha, who built the south tower; and Sarıca Pasha, who built the north tower. The Sultan himself personally inspected the activities on the site.

Architecture

[edit]

The Rumelihisarı fortification has one small tower, three main towers, and thirteen small watchtowers placed on the walls connecting the main towers. One watchtower is in the form of a quadrangular prism, six watchtowers are shaped as prisms with multiple corners, and six others are cylindrical.

The main tower in the north, Sarıca Pasha Tower, is cylindrical in form, with a diameter of 23.30 m (76.4 ft), walls that are 7 m (23 ft) thick, and a total of 9 stories reaching a height of 28 m (92 ft). Today, this tower is also known as Fatih ("Conqueror") Tower after Sultan Mehmed II's cognomen. The large tower at the waterfront in the middle of the fortress, Halil Pasha Tower, is a dodecagonal prism, and also has 9 stories. It is 22 m (72 ft) high with a 23.30 m (76.4 ft) diameter, and walls measuring 6.50 m (21.3 ft) thick. The main tower in the south, Zağanos Pasha Tower, has only 8 stories. This cylindrical tower is 21 m (69 ft) high, and has a 26.70 m (87.6 ft) diameter with 5.70 m (18.7 ft) thick walls. The space within each tower was divided up with wooden floors, each equipped with a furnace. Conical wooden roofs covered with lead originally crowned the towers, although these no longer survive today.

The outer curtain walls of the fortress are 250 m (820 ft) long from north to south, and vary between 50 and 125 m (164 and 410 ft) long from east to west. The complex's total area is 31,250 m2 (336,372 sq ft).

The fortress had three main gates next to the main towers, one side gate and two secret gates for the arsenal and food cellars next to the southern tower. There were wooden houses for the soldiers and a small mosque, endowed by the Sultan at the time of construction. Only the minaret shaft remains of the original mosque, while the small masjid added in the mid-16th century has not survived. A new mosque has since been built in the grounds. Water was supplied to the fortress from a large cistern underneath the mosque and distributed through three wall-fountains, of which only one remains. Two inscriptive plaques are found attached to the walls.

The fortress was initially called "Boğazkesen", literally meaning "Strait Cutter", referring to the Bosporus Strait. The name carries a secondary and more macabre meaning; as boğaz not only means strait but also "throat" in Turkish.

It was later renamed as Rumelihisarı, which means "Fortress on the Land of the Romans", i.e. Byzantine Europe, or the Balkan peninsula.

Usage in the past

[edit]

A battalion of 400 Janissaries was stationed in the fortress, and large cannons were placed in the Halil Pasha Tower, the main tower on the waterfront. Having completed his fortresses, Mehmed proceeded to levy a toll on ships passing within reach of their cannon. A Venetian vessel ignoring signals to stop was sunk with a single shot and all the surviving sailors beheaded,[3] except for the captain, who was impaled and mounted as a human scarecrow as a warning to further sailors on the strait.[4] These cannons were later used until the second half of the 19th century to greet the sultan when he passed by sea.

After the conquest of Constantinople, the fortress served as a customs checkpoint. Rumelihisarı, designated to control the passage of ships through the strait, eventually lost its strategic importance when a second pair of fortresses was built farther up the Bosphorus, where the strait meets the Black Sea. In the 17th century, it was used as a prison, primarily for foreign prisoners of war. Rumelihisarı was partly destroyed by an earthquake in 1509 but was repaired soon after. In 1746, a fire destroyed all the wooden parts in two of the main towers. The fortress was repaired by Sultan Selim III (1761–1807). However, a new residential neighborhood was formed inside the fortress after it was abandoned in the 19th century.

Modern history

[edit]In 1953, on the orders of President Celal Bayar, the inhabitants were relocated and extensive restoration work began on 16 May 1955, which lasted until 29 May 1958. Since 1960 Rumelihisarı has been a museum.

The Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge, named after the Ottoman Sultan that commissioned Rumelihisarı and conquered the city, is located close to the fortress, to the north.

Rumelihisarı is open to public every day except Mondays from 9:00 to 16:30.

The fortress was depicted on various Turkish banknotes during 1939–1986.[5]

Gallery

[edit]-

Rumelihisarı entrance

-

Rumelihisarı Halil Paşa tower

-

Rumelihisarı view with Bosporus

-

Rumelihisarı Saruca Paşa tower.

-

Rumelihisarı Small Zaganos Paşa tower

-

Rumelihisarı Zaganos Paşa tower interior

-

Rumelihisarı's Fatih Mosque

-

Rumelihisarı minaret above cistern.

See also

[edit]|

|

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b "Bosphorus (i.e. Bosporus), View from Kuleli, Constantinople, Turkey". World Digital Library. 1890–1900. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ^ Crowley, Roger (2006). 1453: The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West. Hachette Books. p. 57. ISBN 1401308503.

- ^ Silburn, P. A. B. (1912).

- ^ "BBC Four - Byzantium: A Tale of Three Cities". BBC. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- ^ The fortress was depicted in the following Turkish banknotes:

- On the reverse of the 1 lira banknote of 1942-1947 (2. Emission Group - One Turkish Lira - I. Series Archived 2009-04-16 at the Wayback Machine).

- On the reverse of the 500 lira banknotes of 1939-1946 (2. Emission Group - Five Hundred Turkish Lira - I. Series Archived 2009-05-10 at the Wayback Machine & II. Series Archived 2009-05-10 at the Wayback Machine).

- On the reverse of the 100 lira banknote of 1947-1952 (4. Emission Group - One Hundred Turkish Lira - I. Series Archived 2009-05-10 at the Wayback Machine).

- On the reverse of the 1000 lira banknote of 1953-1979 (5. Emission Group - One Thousand Turkish Lira - I. Series Archived 2009-05-10 at the Wayback Machine).

- On the reverse of the 1000 lira banknotes of 1978-1986 (6. Emission Group - One Thousand Turkish Lira - I. Series Archived 2009-05-10 at the Wayback Machine, II. Series Archived 2009-05-10 at the Wayback Machine & III. Series Archived 2009-05-10 at the Wayback Machine).

- Freely, John (2000). Blue Guide Istanbul. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32014-6.

- Silburn, P. A. B. (1912). The evolution of sea-power. London: Longmans, Green and Co.