Helter Skelter (song)

| "Helter Skelter" | |

|---|---|

Picture sleeve for the 1976 limited jukebox-only single re-release (reverse) | |

| Song by the Beatles | |

| from the album The Beatles | |

| Released | 22 November 1968 |

| Recorded | 18 July, 9–10 September 1968 |

| Studio | EMI, London |

| Genre | |

| Length |

|

| Label | Apple |

| Songwriter(s) | Lennon–McCartney |

| Producer(s) | George Martin |

"Helter Skelter" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1968 album The Beatles (also known as the "White Album"). It was written by Paul McCartney and credited to Lennon–McCartney. The song was McCartney's attempt to create a sound as loud and dirty as possible. It is regarded as a key influence in the early development of heavy metal. In 1976, the song was released as the B-side of "Got to Get You into My Life" in the United States, to promote the Capitol Records compilation Rock 'n' Roll Music.

Along with other tracks from the White Album, "Helter Skelter" was interpreted by cult leader Charles Manson as a message predicting inter-racial war in the US. A vision of this uprising was named after the song. Rolling Stone magazine ranked "Helter Skelter" 52nd on its list of "The 100 Greatest Beatles Songs". Siouxsie and the Banshees, Mötley Crüe, Aerosmith, U2, Oasis and Pat Benatar are among the artists who have covered the track, and McCartney has frequently performed it in concert.

Background and inspiration

[edit]

Paul McCartney was inspired to write "Helter Skelter" after reading an interview with the Who's Pete Townshend in which he described their September 1967 single, "I Can See for Miles", as the loudest, rawest, dirtiest song the Who had ever recorded. McCartney said he then wrote "Helter Skelter" to have "the most raucous vocal, the loudest drums".[6] On 20 November 1968, two days before the release of The Beatles (also known as "the White Album"),[7] McCartney gave Radio Luxembourg an exclusive interview, in which he commented on several of the album's songs.[8] Speaking of "Helter Skelter", he said:

...I'd read a review of a record which said, "and this group really got us wild, there's echo on everything, they're screaming their heads off." And I just remember thinking, "Oh, it'd be great to do one. Pity they've done it. Must be great – really screaming record." And then I heard their record and it was quite straight, and it was very sort of sophisticated. It wasn't rough and screaming and tape echo at all. So I thought, "Oh well, we'll do one like that, then." And I had this song called "Helter Skelter," which is just a ridiculous song. So we did it like that, 'cos I like noise.[9]

In British English, a helter skelter is a fairground attraction consisting of a tall spiral slide winding around a tower; however, the phrase can also mean chaos and disorder.[10] McCartney said that he was "using the symbol of a helter skelter as a ride from the top to the bottom; the rise and fall of the Roman Empire – and this was the fall, the demise."[6] He later said that the song was a response to critics who accused him of writing only sentimental ballads and being "the soppy one" of the band.[11] Although the song is credited to the Lennon–McCartney partnership, it was written by McCartney alone.[12] John Lennon acknowledged in a 1980 interview: "That's Paul completely."[13]

Composition

[edit]The song is in the key of E major[14] and in a 4

4 time signature.[15] On the recording issued on The Beatles, its structure comprises two combinations of verse and chorus, followed by an instrumental passage and a third verse–chorus combination. This is followed by a prolonged ending during which the performance stops, picks up again, fades out, fades back in, and then fades out one final time amidst a cacophony of sounds.[15] The stereo mix features one more section that fades in and concludes the song.[16]

The only chords used in the song are E7, G and A, with the first of these being played throughout the extended ending. Musicologist Walter Everett comments on the musical form: "There is no dominant and little tonal function; organized noise is the brief."[17] The lyrics initially follow the title's fairground theme, from the opening line "When I get to the bottom I go back to the top of the slide". McCartney completes the first half-verse with a hollered "and then I see you again!"[18] The lyrics then become more suggestive and provocative, with the singer asking, "But do you, don't you, want me to love you?"[19] In author Jonathan Gould's description, "The song turns the colloquialism for a fairground ride into a metaphor for the sort of frenzied, operatic sex that adolescent boys of all ages like to fantasize about."[20]

Recording

[edit]"Helter Skelter" was recorded several times during the sessions for the White Album. During the 18 July 1968 session, the Beatles recorded take 3 of the song, lasting 27 minutes and 11 seconds.[21] However, this version differs greatly from, and is slower than, the album version.[22][nb 1] Chris Thomas produced the 9 September session in George Martin's absence.[2] He recalled the session was especially spirited: "While Paul was doing his vocal, George Harrison had set fire to an ashtray and was running around the studio with it above his head, doing an Arthur Brown."[23][nb 2] Ringo Starr recalled: "'Helter Skelter' was a track we did in total madness and hysterics in the studio. Sometimes you just had to shake out the jams."[25]

On 9 September, 18 takes lasting approximately five minutes each were recorded, with the last one featured on the original LP.[23] At around 3:40, the song completely fades out, then gradually fades back in, fades back out partially, and finally fades back in quickly with three cymbal crashes and shouting from Starr.[26] During the end of the 18th take, he threw his drum sticks across the studio[16] and screamed, "I got blisters on my fingers!"[6][23][nb 3] Starr's shout was only included on the stereo mix of the song; the mono version (originally on LP only) ends on the first fadeout without Starr's outburst.[28][nb 4] On 10 September, the band added overdubs which included a lead guitar part by Harrison, trumpet played by Mal Evans, piano, further drums, and "mouth sax" created by Lennon blowing through a saxophone mouthpiece.[28]

According to music critic Tim Riley, although McCartney and Lennon had diverged markedly as songwriters during this period, the completed track can be seen as a "competitive apposition" to Lennon's "Everybody's Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey". He says that whereas Lennon "submerges in scatalogical contradictions" in his song, "Helter Skelter" "ignites a scathing, almost violent disorder".[30] In Everett's view, rather than the Who's contemporaneous music, the song "sounds more like an answer to [Yoko Ono]", the Japanese performance artist who, as Lennon's new romantic partner, was a constant presence at the White Album sessions and a source of tension within the band.[31]

Musicologists Kenny Jenkins (of Leeds Beckett University) and Richard Perks (of University of Kent) have expressed the opinion that a Bartell fretless guitar belonging to Harrison was used on this track.[32]

Release and reception

[edit]"Helter Skelter" was sequenced as the penultimate track on side three of The Beatles, between "Sexy Sadie" and "Long, Long, Long".[33][34] The segue from "Sexy Sadie" was a rare example of a gap (or "rill") being used to separate the album's tracks, and the brief silence served to heighten the song's abrupt arrival.[35] In Riley's description, the opening guitar figure "demolishes the silence ... from a high, piercing vantage point" while, at the end of "Helter Skelter", the meditative "Long, Long, Long" begins as "the smoke and ash are still settling".[36] The double LP was released by Apple Records on 22 November 1968.[7][37]

In his contemporary review for International Times, Barry Miles described "Helter Skelter" as "probably the heaviest rocker on plastic today",[38] while the NME's Alan Smith found it "low on melody but high on atmosphere" and "frenetically sexual", adding that its pace was "so fast they all only just about keep up with themselves".[39] Record Mirror's reviewer said the track contained "screaming pained vocals, ear splitting buzz guitar and general instrumental confusion, but [a] rather typical pattern", and concluded: "Ends sounding like five thousand large electric flies out for a good time. Ringo then blurts out with excruciating torment: 'I got blisters on my fingers![40]

In his review for Rolling Stone, Jann Wenner wrote that the Beatles had been unfairly overlooked as hard rock stylists, and he grouped the song with "Birthday" and "Everybody's Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey" as White Album tracks that captured "the very best traditional and contemporary elements in rock and roll". He described "Helter Skelter" as "excellent", highlighting its "guitar lines behind the title words, the rhythm guitar track layering the whole song with that precisely used fuzztone, and Paul's gorgeous vocal".[41] Geoffrey Cannon of The Guardian praised it as one of McCartney's "perfect, professional songs, packed with exact quotes and characterisation", and recommended the stereo version for the way it "transforms" the song "from a nifty fast number to one of my best 30 tracks of all time".[42] Although he misidentified it as a Lennon song, William Mann of The Times said "Helter Skelter" was "exhaustingly marvellous, a revival that is willed by creativity ... into resurrection, a physical but essentially musical thrust into the loins".[43]

In June 1976, Capitol Records included the track on its themed double album compilation Rock 'n' Roll Music. In the United States, the song was also issued on the single promoting the album, as the B-side to "Got to Get You into My Life".[44] In 2012, "Helter Skelter" appeared on the iTunes compilation album Tomorrow Never Knows, which the band's website described as a collection of "the Beatles' most influential rock songs".[45]

On the Beatles' 2006 remix album Love, the song was remixed in mashup along with "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!", and snippets of that song and "I Want You (She's So Heavy)" are mixed in with the repeated guitar riff. [46][47] The mix also included the organ solo and the guitar solo from the Trident studio outtake.

Charles Manson interpretation

[edit]

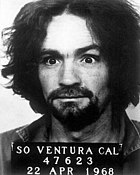

According to Los Angeles Deputy District Attorney Vincent Bugliosi, who led the prosecution of Manson and four of his followers who acted on Manson's instruction in the Tate–LaBianca murders, Charles Manson told his followers that several White Album songs, particularly "Helter Skelter",[48] were part of the Beatles' coded prophecy of an apocalyptic war in which racist and non-racist whites would be manoeuvred into virtually exterminating each other over the treatment of blacks.[49][50][51] Upon the war's conclusion, after black militants had killed off the few whites that had survived, Manson and his "Family" of followers would emerge from an underground city in which they would have escaped the conflict. As the only remaining whites, they would rule blacks, who, as the vision went, would be incapable of running the United States.[52] Manson employed "Helter Skelter" as the term for this sequence of events.[53][54] In his interpretation, the lyrics of the Beatles' "Helter Skelter" described the moment when he and the Family would emerge from their hiding place – a disused mine shaft in the desert outside Los Angeles.[55]

Bugliosi named his best-selling book about the murders Helter Skelter.[56] At the scene of the LaBianca murders in August 1969, the phrase (misspelt as "HEALTER SKELTER") was found written in the victims' blood on the refrigerator door.[57][58] In October 1970, Manson's defence team announced that they would call on Lennon for his testimony. Lennon responded that his comments would be of no use, since he had no hand in writing "Helter Skelter".[59]

Bugliosi's book was the basis for the 1976 television film Helter Skelter. The film's popularity in the US ensured that the song, and the White Album generally, received a new wave of attention. As a result, Capitol planned to issue "Helter Skelter" as the A-side of the single from Rock 'n' Roll Music but relented, realising that to exploit its association with Manson would be in poor taste.[44] In the final interview he gave before his murder in December 1980, Lennon dismissed Manson as "just an extreme version" of the type of listener who read false messages in the Beatles' lyrics, such as those behind the 1969 "Paul is dead" rumour.[60] Lennon also said: "All that Manson stuff was built around George's song about pigs ['Piggies'] and this one, Paul's song about an English fairground. It has nothing to do with anything, and least of all to do with me."[13]

Reflecting on "Helter Skelter" and its appropriation by the Manson Family in his 1997 authorised biography, Many Years from Now, McCartney said, "Unfortunately, it inspired people to do evil deeds" and that the song had acquired "all sorts of ominous overtones because Manson picked it up as an anthem".[61] Author Devin McKinney describes the White Album as "also a black album" in that it is "haunted by race".[62] He writes that, in spite of McCartney's comments about the song's meaning, the recording conveys a violent subtext typical of much of the album and that "Here as ever in Beatle music, performance determines meaning; and as the adrenalized guitars run riot, the meaning is simple, dreadful, inarticulate, and instantly understood: She's coming down fast."[1] In her 1979 essay collection, titled The White Album, Joan Didion wrote that many people in Los Angeles cite the moment that news arrived of the Manson Family's killing spree in August 1969 as having marked the end of the decade.[63] According to author Doyle Greene, the Beatles' "Helter Skelter" effectively captured the "crises of 1968", which contrasted sharply with the previous year's Summer of Love ethos. He adds: "While 'Revolution' posited a forthcoming unity as far as social change, 'Helter Skelter' signified a chaotic and overwhelming sense of falling apart occurring throughout the world politically and, not unrelated, the falling apart of the Beatles as a working band and the counterculture dream they represented."[64]

This theory was introduced by Bugliosi in Manson's trial. Mike McGann, the lead police investigator on the Tate–LaBianca murders stated, "Everything in Vince Bugliosi's book (Helter Skelter) is wrong. I was the lead investigator on the case. Bugliosi didn't solve it. Nobody trusted him." Police detective Charlie Guenther who investigated the murders and Bugliosi's co-prosecutor Aaron Stovits have also discredited this as the motive for the murders.[65]

Retrospective reviews and legacy

[edit]Writing for MusicHound in 1999, Guitar World editor Christopher Scapelliti grouped "Helter Skelter" with "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" and "Happiness Is a Warm Gun" as the White Album's three "fascinating standouts".[66] The song was noted for its "proto-metal roar" by AllMusic reviewer Stephen Thomas Erlewine.[67] Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the album's release, Jacob Stolworthy of The Independent listed the same three songs as its best tracks, with "Helter Skelter" ranked at number 3. Stolworthy described it as "one of the best rock songs ever recorded" and concluded: "The fiercest, most blistering track that arguably paved the way for heavy metal is far removed from the tame love songs people were used to from [McCartney]."[68] Writing in 2014, Ian Fortnam of Classic Rock magazine cited "Helter Skelter" as one of the four songs that made the Beatles' White Album an "enduring blueprint for rock", along with "While My Guitar Gently Weeps", "Yer Blues" and "Don't Pass Me By", in that together they contained "every one of rock's key ingredients".[69] In the case of McCartney's song, he said that the track was "one of the prime progenitors of heavy metal" and a major influence on 1970s punk rock.[70]

Ian MacDonald dismissed "Helter Skelter" as "ridiculous, [with] McCartney shrieking weedily against a massively tape-echoed backdrop of out-of-tune thrashing", and said that in their efforts to embrace heavy rock, the Beatles "comically overreached themselves, reproducing the requisite bulldozer design but on a Dinky Toy scale". He added: "Few have seen fit to describe this track as anything other than a literally drunken mess."[71] Rob Sheffield was also unimpressed, writing in The Rolling Stone Album Guide (2004) that, following the double album's release on CD, "now you can program 'Sexy Sadie' and 'Long, Long, Long' without having to lift the needle to skip over 'Helter Skelter.'"[72] David Quantick, in his book Revolution: The Making of the Beatles' White Album, describes the song as "Neither loud enough to bludgeon the listener into being impressed nor inspired enough to be exciting". He says that it becomes "a bit dull after two minutes" and, after its laboured attempts at an ending, is "redeemed only" by Starr's closing remark.[73]

Doyle Greene argues that the Beatles and Manson are "permanently connected in pop-culture consciousness" as a result of Manson's supposed interpretation of "Helter Skelter", "Piggies" and other tracks from the White Album.[74] "Helter Skelter" was voted the fourth worst song in one of the first polls to rank the Beatles' songs, conducted in 1971 by WPLJ and The Village Voice.[75] According to Walter Everett, it is typically among the five most-disliked Beatles songs for members of the baby boomer generation, who made up the band's contemporary audience during the 1960s.[76]

In March 2005, Q magazine ranked "Helter Skelter" at number 5 in its list of the "100 Greatest Guitar Tracks Ever".[77] The song appeared at number 52 in Rolling Stone's 2010 list of "The 100 Greatest Beatles Songs".[26][78] In 2018, Kerrang! selected it as one of "The 50 Most Evil Songs Ever" due to its association with the Manson Family murders.[79]

Cover versions

[edit]Since the producers of the 1976 film Helter Skelter were denied permission to use the Beatles recording, the song was re-recorded for the soundtrack by the band Silverspoon.[80] Siouxsie and the Banshees included a cover of "Helter Skelter" at live shows from mid 1977,[81] and recorded it as a Peel Session in 1978,[82] before releasing a version later that year, produced by Steve Lillywhite, on their debut album The Scream.[83][84] Fortnam cites the band's choice as reflective of how the song's "macabre association with Charles Manson ... only served to accentuate its enduring appeal in certain quarters".[85][nb 5] While discussing the stereo and mono versions of the Beatles' 1968 recording and the best-known cover versions of the track up to 2002, Quantick highlights the Siouxsie and the Banshees recording as "the best of all of them".[73][nb 6] In an article about the legacy of the song, Financial Times further commented the Banshees' version, saying: "The abrupt ending on “stop” also leaves the listener mentally stuck at the top of the slide with no way down".[87]

In 1983, Mötley Crüe included the song on their album Shout at the Devil. Nikki Sixx, the band's bassist, recalled that "Helter Skelter" appealed to them through its guitars and lyrics, but also because of the Manson murders and the song's standing as a "real symbol of darkness and evil".[88] Mötley Crüe's 1983 picture disc for the song featured a photo of a fridge with the title written in blood.[88] That same year, the Bobs released an a-cappella version on their album The Bobs.[89] It earned them a 1984 Grammy nomination for Best Vocal Arrangement for Two or More Voices.[90]

In 1988, a U2 recording was used as the opening track on their album Rattle and Hum. The song was recorded live at the McNichols Sports Arena in Denver, Colorado on 8 November 1987.[91] Introducing the song, Bono said, "This is a song Charles Manson stole from the Beatles. We’re stealing it back."[80] Aerosmith included a cover of "Helter Skelter", recorded in 1975, on their 1991 compilation Pandora's Box compilation.[92] Aerosmith's version charted at number 21 on the Album Rock Tracks chart in the US.[93]

"Helter Skelter" has been covered by many other artists, including Pat Benatar, Vow Wow, Hüsker Dü, Dianne Heatherington and Thrice.[94] Shock rock artist Rob Zombie collaborated with Marilyn Manson on a cover of "Helter Skelter", which was released in 2018 to promote their co-headlining "Twins of Evil: The Second Coming Tour".[95][96] Their version peaked at number nine on Billboard's Hard Rock Digital Songs.[97] Swiss industrial black metal band Samael covered the song on their 2017 album Hegemony, with a music video released in 2021 where they credit "Helter Skelter" as being the "first metal song ever recorded".[98]

McCartney live performances

[edit]Since 2004, McCartney has frequently performed "Helter Skelter" in concert. The song featured in the set lists for his '04 Summer Tour, The 'US' Tour (2005), Summer Live '09 (2009), the Good Evening Europe Tour (2009), the Up and Coming Tour (2010–11) and the On the Run Tour (2011–12).[80] He also played it on his Out There Tour, which began in May 2013. In the last tours, the song has been generally inserted on the third encore, which is the last time the band enters the stage. It is usually one of the last songs, performed after "Yesterday" and before the final medley including "The End". McCartney played the song on his One on One Tour at Fenway Park on 17 July 2016 accompanied by the Grateful Dead's Bob Weir and New England Patriots football player Rob Gronkowski.[citation needed]

McCartney performed the song live at the 48th Annual Grammy Awards on 8 February 2006 at the Staples Center in Los Angeles. In 2009, he performed it live on top of the Ed Sullivan Theater marquee during his appearance on the Late Show with David Letterman.[80]

At the 53rd Grammy Awards in 2011, the version of the song from McCartney's live album Good Evening New York City, recorded during the Summer Live '09 tour, won in the category of Best Solo Rock Vocal Performance.[99][100] It was his first solo Grammy Award since he won for arranging "Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey" in 1972.[101] McCartney opened his set at 12-12-12: The Concert for Sandy Relief with the song.[102] On 13 July 2019, the final date of his Freshen Up tour,[103] McCartney performed "Helter Skelter" at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles with Starr playing drums.[104]

Personnel

[edit]According to Mark Lewisohn[23] and Walter Everett:[105]

- Paul McCartney – lead vocal, backing vocal, lead/rhythm guitar, fender jazz Bass on September 9th session,

- John Lennon – backing vocal, six-string bass on the slow version in July, sound effects (through tenor saxophone mouthpiece), piano[106]

- George Harrison – backing vocal, lead/rhythm guitar, slide guitar

- Ringo Starr – drums, vocal shout

- Mal Evans – trumpet

Notes

[edit]- ^ Take 2, recorded the same day, originally 12 minutes and 54 seconds long, was edited down to 4:35 for Anthology 3.[22]

- ^ Harrison's antics were in reference to Brown's contemporary hit song "Fire".[24]

- ^ Some sources erroneously credit the "blisters" line to Lennon;[26] in fact, Lennon can be heard asking "How's that?" before Starr's outburst.[27]

- ^ This version was not initially available in the United States as mono albums had already been phased out there.[29] The mono version was later released on the American version of the Rarities album.[28] In 2009, it was made available on the CD mono reissue of The Beatles as part of the Beatles in Mono box set.

- ^ He also comments on the significance of Chris Thomas having become "one of punk's leading sonic architects" by the late 1970s, with his production of the Sex Pistols' Never Mind the Bollocks.[85]

- ^ Matt Harvey of BBC Music describes the Banshees' hit recording of the White Album track "Dear Prudence" as "surprisingly dull" but admires their version of "Helter Skelter" as a "magnificent deconstruction" and "one of the greatest covers of all time".[86]

References

[edit]- ^ a b McKinney 2003, p. 231.

- ^ a b Winn 2009, p. 210.

- ^ Riley 2002, p. 24.

- ^ Athitakis, Mark (September–October 2013). "A Beatles Reflection". Humanities. National Endowment of the Humanities. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Inglis 2009, p. 121.

- ^ a b c Miles 1997, pp. 487–88.

- ^ a b Miles 2001, p. 314.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 224.

- ^ "Radio Luxembourg interview, Paul McCartney (20 November 1968)". Beatles Interview Database. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ^ "Definition of helter-skelter". AskOxford. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, pp. 310–11.

- ^ Womack 2014, pp. 381–82.

- ^ a b Sheff 2000, p. 200.

- ^ MacDonald 2007, p. 495.

- ^ a b Pollack, Alan W. (7 June 1998). "Notes on 'Helter Skelter'". Soundscapes. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ a b Spitz 2005, p. 794.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 191.

- ^ Riley 2002, p. 281.

- ^ O'Toole, Kit (25 July 2018). "The Beatles, 'Helter Skelter' from The White Album (1968): Deep Beatles". Something Else!. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 520.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 143.

- ^ a b Winn 2009, p. 190.

- ^ a b c d Lewisohn 2005, p. 154.

- ^ Quantick 2002, p. 139.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, p. 311.

- ^ a b c Womack 2014, p. 382.

- ^ Winn 2009, pp. 210–11.

- ^ a b c Winn 2009, p. 211.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 321.

- ^ Riley 2002, p. 261.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 165, 347.

- ^ "George Harrison: A Rare Bartell Fretless Electric Guitar owned by George Harrison, believed made circa 1967". Bonhams. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 319.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 164.

- ^ McKinney 2003, p. 238.

- ^ Riley 2002, pp. 281, 282.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 163.

- ^ Miles, Barry (29 November 1968). "Multi-Purpose Beatles Music". International Times. p. 10.

- ^ Smith, Alan (9 November 1968). "Beatles Double-LP in Full". NME. p. 5.

- ^ Starr, Ringo (9 September 2023). "Helter Skelter': The Story Behind The Beatles Classic". uDiscoverMusic.

- ^ Wenner, Jann S. (21 December 1968). "Review: The Beatles' 'White Album'". Rolling Stone. p. 10. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ Cannon, Geoffrey (26 November 1968). "Back to Spring: The Beatles: The Beatles (White Album) (Apple)". The Guardian. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Mann, William (22 November 1968). "The New Beatles Album". The Times.

- ^ a b Schaffner 1978, p. 187.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 918.

- ^ Willman, Chris (26 December 2006). "peace". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 6 January 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ Webb, Adam (20 November 2006). "The Beatles: LOVE". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ Doggett 2007, p. 394.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1994, pp. 240–247.

- ^ Linder, Douglas (2007). "Testimony of Paul Watkins in the Charles Manson Trial". The Trial of Charles Manson. University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on 20 March 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- ^ Linder, Douglas (2007). "The Influence of the Beatles on Charles Manson". The Trial of Charles Manson. University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on 21 December 2002. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- ^ Doggett 2007, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Lachman 2001, p. 262.

- ^ Quantick 2002, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 489–490.

- ^ Lachman 2001, p. 276.

- ^ Lachman 2001, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Paytress, Mark (2003). "Family Misfortunes". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days of Revolution (The Beatles' Final Years – Jan 1, 1968 to Sept 27, 1970). London: Emap. p. 106.

- ^ Doggett 2007, pp. 393–394.

- ^ Sheff 2000, p. 88.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 488.

- ^ McKinney 2003, p. 232.

- ^ Gould 2007, pp. 509–510, 595.

- ^ Greene 2016, pp. 51–52.

- ^ O'Neill, Tom (2019). Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties. Little, Brown. pp. 104, 149, 151–152. ISBN 978-0-316-47757-4. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Graff & Durchholz 1999, p. 88.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Beatles The Beatles [White Album]". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Stolworthy, Jacob (22 November 2018). "The Beatles' White Album tracks, ranked – from Blackbird to While My Guitar Gently Weeps". The Independent. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ Fortnam 2014, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Fortnam 2014, pp. 43–44.

- ^ MacDonald 2007, p. 298.

- ^ Brackett & Hoard 2004, p. 53.

- ^ a b Quantick 2002, p. 138.

- ^ Greene 2016, p. 197.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 217.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 279.

- ^ UG Team (21 March 2005). "Greatest Guitar Tracks". Ultimate Guitar. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "100 Greatest Beatles Songs". rollingstone.com. 19 September 2011. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Kerrang! staff (28 September 2018). "The 50 Most Evil Songs Ever". Kerrang!. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Womack 2014, p. 383.

- ^ "The Scream: Tour - '11/07/77 - London, Vortex Club Helter Skelter (Live debut) ...09/07/77 - Shad Thames, Butler's Wharf, London (private party hosted by Derek Jarman and Andrew Logan.) Helter Skelter/The Lord's Prayer (Private live debut) ... 17/05/77 - Manchester, The Royal Oak Helter Skelter ..'". Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "20 Minutes To 20 Years – The Banshees' Tale "Another Peel session in February, with the new Hong Kong Garden, Overground, Carcass and their terrifying disembowelment of The Beatles' Helter Skelter, stepped up the pressure."". 4 October 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Clark, Carol (15 February 2018). "The story behind the song: Dear Prudence by Siouxsie and the Banshees". Louder Sound. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Johnston, Chris. "The Crate: Siouxsie and the Banshees faithfully cover the Beatles' Dear Prudence". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ a b Fortnam 2014, p. 44.

- ^ Harvey, Matt (2002). "Siouxsie and The Banshees The Best of Siouxsie and the Banshees Review". BBC Music. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Fildes, Nic (3 May 2021). "Helter Skelter — The Beatles' brutal song that inspired a murder spree". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ a b Fortnam 2014, p. 41.

- ^ "The Bobs – The Bobs". AllMusic. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ 1984 Grammy award nomination, Best Vocal Arrangement for Two or More Voices, Richard Greene, Gunnar Madsen – Helter Skelter (The Bobs) LA Times, "The Envelope" awards database, accessed 2010 Jan 13.

- ^ "U2 – Helter Skelter". U2songs.com. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "Pandora's Box – Aerosmith". AllMusic. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ Colombo, Anthony (16 November 1991). "Album Rock Tracks". Billboard. p. 16.

- ^ Fontenot, Robert. "The Beatles Songs: 'Helter Skelter' – The history of this classic Beatles song". oldies.about.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Bienstock, Richard (11 July 2018). "Hear Marilyn Manson, Rob Zombie Cover Beatles' 'Helter Skelter'". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ Kaufman, Spencer (11 July 2018). "Rob Zombie and Marilyn Manson team up for cover of The Beatles' "Helter Skelter": Stream". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson - Chart History (Hard Rock Digital Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ Samael release official music video for Beatles cover “Helter Skelter” Archived 13 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine Abaddon Magazine. 13 December 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Womack 2014, pp. 331–32.

- ^ Final Nominations List, 53rd Grammy Awards Archived 14 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Retrieved on 10 February 2011.

- ^ [1][permanent dead link] Yahoo! Entertainment Story – Reuters. Retrieved on 13 February 2011.[dead link]

- ^ '12-12-12': Paul McCartney fronts Nirvana 'reunion' and more highlights from Sandy benefit concert Archived 14 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Larsen, Peter (14 July 2019). "Paul McCartney reunites with Ringo Starr at Dodger Stadium during career-spanning show". dailynews.com. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ Hobbs, Thomas (14 July 2019). "With a little help from my friends: Watch Paul McCartney bring out Ringo Starr for the final night of his US tour". nme.com. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 191, 347.

- ^ Howlett, Kevin (2018). The Beatles (50th Anniversary Super Deluxe Version) (book). Apple Records.

Sources

[edit]- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8.

- Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian, eds. (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). New York, NY: Fireside/Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Bugliosi, Vincent; Gentry, Burt (1994). Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders (25th Anniversary ed.). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-08700-X.

- Doggett, Peter (2007). There's a Riot Going On: Revolutionaries, Rock Stars, and the Rise and Fall of '60s Counter-Culture. Edinburgh, UK: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-84195-940-5.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512941-0.

- Fortnam, Ian (October 2014). "You Say You Want a Revolution ...". Classic Rock. pp. 33–46.

- Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America. London: Piatkus. ISBN 978-0-7499-2988-6.

- Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel, eds. (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- Greene, Doyle (2016). Rock, Counterculture and the Avant-Garde, 1966–1970: How the Beatles, Frank Zappa and the Velvet Underground Defined an Era. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-6214-5.

- Hertsgaard, Mark (1996). A Day in the Life: The Music and Artistry of the Beatles. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-33891-9.

- Inglis, Ian (2009). "Revolution". In Womack, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68976-2.

- Lachman, Gary (2001). Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius. New York, NY: The Disinformation Company. ISBN 0-9713942-3-7.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2005) [1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 978-0-7537-2545-0.

- MacDonald, Ian (2007). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties. Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-733-3.

- McKinney, Devin (2003). Magic Circles: The Beatles in Dream and History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01202-X.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now. New York, NY: Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 0-8050-5249-6.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- Quantick, David (2002). Revolution: The Making of the Beatles' White Album. Chicago, IL: A Cappella Books. ISBN 1-55652-470-6.

- Riley, Tim (2002) [1988]. Tell Me Why – The Beatles: Album by Album, Song by Song, the Sixties and After. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81120-3.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Sheff, David (2000) [1981]. All We Are Saying: The Last Major Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-25464-4.

- Sounes, Howard (2010). Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-723705-0.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. Boston, MA: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-80352-9.

- Winn, John C. (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.

- Womack, Kenneth (2014). The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39171-2.