Henry Wirz

Henry Wirz | |

|---|---|

Wirz c. 1865 | |

| Born | Hartmann Heinrich Wirz November 25, 1823 |

| Died | November 10, 1865 (aged 41) Old Capitol Prison, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Burial place | Mount Olivet Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Spouses | Emilie Oschwald

(m. 1845; div. 1853)Elizabeth Wolfe (m. 1854) |

| Children | 3 |

| Conviction(s) |

|

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | Confederate States of America |

| Service | Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Commands | Andersonville Prison |

| Battles / wars | |

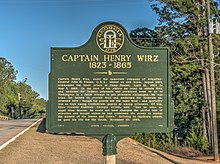

Henry Wirz (born Hartmann Heinrich Wirz; November 25, 1823 – November 10, 1865) was a Swiss-American convicted war criminal who served as a Confederate Army officer during the American Civil War.[1] He was the commandant of Andersonville Prison, a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp near Andersonville, Georgia, where nearly 13,000 Union Army prisoners of war died as result of inhumane conditions. After the war, Wirz was tried and executed for conspiracy and murder relating to his command of the camp; this made the captain the highest-ranking soldier and only officer of the Confederate Army to be sentenced to death for crimes during their service.[2] Since his execution, Wirz has become a controversial figure due to debate about his guilt and reputation, including criticism over his personal responsibility for Andersonville Prison's conditions and the quality of his post-war trial.

Early life and career

[edit]Wirz was born Hartmann Heinrich Wirz on November 25, 1823, in Zürich, Switzerland, to Johann Caspar Wirz, a master tailor and member of Zürich's city council,[3] and Sophie Barbara Philipp.[1][4][5] Wirz received elementary and secondary education, and he aspired to become a physician but his family did not possess funds to pay for his medical education. Instead, he was educated as a merchant in Zürich and Turin from 1840 until 1842, when he began working at the department store of Zürich.[3] He married Emilie Oschwald in 1845[3] and had two children.

In 1847, Wirz was sentenced to four years in prison on charges of embezzlement and fraud.[6] He was released the next year and his sentence was commuted to 12 years of exile from the canton of Zürich,[3] but his wife refused to emigrate and obtained a divorce in 1853.[4] Wirz first went to Moscow,[3] in 1848, and the next year to the United States, where he found employment in a factory in Lawrence, Massachusetts. After five years, he moved to Hopkinsville, Kentucky, and worked as a doctor's assistant.[7] There, he learned to perform small surgeries and cast fractures.[6] He tried to establish his own homeopathic medicine practice in Cadiz, Kentucky, and also worked as superintendent of a water cure clinic in Northampton, Massachusetts.[8]

In 1854, Wirz married the Methodist widow Elizabeth Wolfe (née Savells).[3] Along with her two daughters, they moved to Louisiana, where Wolfe gave birth to their daughter.[6] In 1856 Wirz made the acquaintance of Levin R. Marshall, the owner of the plantation Cabin Teele, who employed him as its overseer and where he set up a practice for homeopathic medicine.[9]

Civil War

[edit]Upon the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, the 37-year-old Wirz enlisted as a private in Company A (Madison Infantry), 4th Battalion of Louisiana Infantry of the Confederate army in Madison Parish.[10][11] Shortly before his death, he said that he had taken part in the Battle of Seven Pines in May 1862, as an aide-de-camp to General Joseph E. Johnston, during which he was wounded by a Minie ball and lost the use of his right arm. That account is disputed by historians,[12] one of whom says the injury may have actually occurred during a six-thousand mile mission to track down missing records of Union prisoners. That journey and a subsequent three months of rehabilitation at his home, were completed by the end of 1862.[1]

After returning to his unit on June 12, 1862, Wirz was promoted to captain "for bravery on the field of battle."[citation needed] Because of his injury, Wirz was assigned to the staff of General John H. Winder, who was in charge of Confederate prisoner-of-war camps, as his adjutant.[13]

Later accounts by Wirz's daughter alleged that Confederate President Jefferson Davis made Captain Wirz a "special minister" and sent him to Europe carrying secret dispatches to Confederate Commissioners James Mason in England, and John Slidell in France.[1] Wirz returned from Europe in January 1864 and reported to Richmond, Virginia, where he began working for General Winder in the prison department. Wirz initially served on detached duty as a prison commandant in Alabama, but was then transferred to help guard Union prisoners incarcerated at Richmond.[citation needed]

Camp Sumter

[edit]

In February 1864, the Confederate government established Camp Sumter, a large military prison near the small railroad depot of Anderson (now Andersonville) in south-western Georgia, built to house Union prisoners-of-war. In April 1864, Wirz arrived at Camp Sumter and remained there for over a year holding the post of commandant of the stockade and its interior.[15] Wirz was praised by his many superiors and even by some prisoners, and was even recommended for, but not promoted to, major.[16]

Camp Sumter had not been constructed to its full plan, and was quickly overwhelmed by the influx of Union prisoners. Though wooden barracks were originally planned, the Confederates incarcerated the prisoners in a vast, rectangular, open-air stockade originally encompassing 16.5 acres (6.7 ha), which had been intended as only a temporary prison pending exchanges of prisoners with the Union. The prisoners gave this place the name "Andersonville", which became the colloquial name for the camp. Camp Sumter suffered from severe overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, and an extreme lack of food, tools, medical supplies, and potable water.[17] Wirz recognized that the conditions were inadequate and petitioned his superiors to provide more support, but was denied. In July 1864, he sent five prisoners to the Union with a petition written by the inmates asking the government to negotiate their release.[citation needed]

At its peak in August 1864 after its expansion to 26 acres, the prison held some 33,000 Union prisoners – around four times more than any other Confederate prison – with little more than patchy tents for shelter. The same summer saw more than 100 prisoners die of disease, exposure, or malnutrition every day. Around 45,000 prisoners were incarcerated during the camp's 14-month existence, of whom close to 13,000 (28%) died.[18][19]

Trial and execution

[edit]Wirz was arrested by a contingent of the 4th U.S. Cavalry on May 7, 1865, in Andersonville. He was taken first to Macon, Georgia, and then by rail to Washington, D.C., arriving there on May 10, 1865, where he was held in the Old Capitol Prison since the federal government decided to put him on trial for conspiring to impair the lives of Union prisoners of war. A special military commission was convened with Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace presiding. The other members were Gershom Mott; John W. Geary; Lorenzo Thomas; Francis Fessenden; Edward S. Bragg; John F. Ballier, U.S. Volunteers; T. Allcock, 4th New York Artillery; and John H. Stibbs, 12th Iowa Volunteers. Col. Norton P. Chipman served as Judge Advocate. During the trial gangrene prevented Wirz from sitting and he spent the trial on a couch.[20]

Charges

[edit]The military tribunal took place between August 23 and October 18, 1865,[21] was held in the United States Court of Claims, and dominated the front pages of newspapers across the United States. Wirz was charged with "combining, confederating, and conspiring, together with John H. Winder, Richard B. Winder, Joseph [Isaiah H.] White, W. S. Winder, R. R. Stevenson, and others unknown, to injure the health and destroy the lives of soldiers in the military service of the United States, then held and being prisoners of war within the lines of the so-called Confederate States, and in the military prisons thereof, to the end that the armies of the United States might be weakened and impaired, in violation of the laws and customs of war" and for "violation of the laws of war, to impair and injure the health and to destroy the lives—by subjecting to torture and great suffering; by confining in unhealthy and unwholesome quarters; by exposing to the inclemency of winter and to the dews and burning sun of summer; by compelling the use of impure water; and by furnishing insufficient and unwholesome food—of large numbers of Federal prisoners."[22] Wirz was accused of committing 13 acts of personal cruelty and murders in August 1864: by revolver (specifications 1, 3, 4), by physically stomping and kicking the victim (specification 2), by confining prisoners in stocks (specifications 5, 6), by beating a prisoner with a revolver (specification 13) and by chaining prisoners together (specification 7).[23] Wirz was also charged with ordering guards to fire on prisoners with muskets (specifications 8, 9, 10, 12) and to have dogs attack a prisoner (specification 11).[24]

Testimonies

[edit]The National Park Service lists 158 witnesses who testified at the trial, including former Camp Sumter prisoners, ex-Confederate soldiers, and residents of nearby Andersonville.[25] According to Benjamin G. Cloyd, 145 testified that they did not observe Wirz kill any prisoners; others failed to identify specific victims.[26] Twelve said that they witnessed cruelty on the part of Wirz. One witness, Felix de la Baume, who claimed to be a descendant of the Marquis de Lafayette, identified under oath a victim allegedly killed personally by Wirz.[27] Among those giving testimony was Father Peter Whelan, a Catholic priest who worked with the inmates, who testified on Wirz's behalf.[25] A former Andersonville guard named James Duncan was called to testify for the defence, but was arrested when he tried to give evidence for allegedly causing the death of a prisoner at Andersonville.[28]

Verdict

[edit]In early November 1865, the Military Commission found Wirz guilty of conspiracy as charged, along with 10 of 13 specifications of acts of personal cruelty, and sentenced him to death. He was acquitted of specifications 4, 10, and 13.[29]

In his report on the trial, the Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, who had prosecuted the Lincoln assassination trials, vilified Wirz and pronounced that "his work of death seems to have been a saturnalia of enjoyment for the prisoner [Wirz], who amid these savage orgies evidenced such exultation and mingled with them such nameless blasphemy and ribald jest, as at times to exhibit him rather as a demon than a man."[30]

In a letter to U.S. President Andrew Johnson, Wirz asked for clemency, but the letter went unanswered. The night before his execution, Louis F. Schade, an attorney working on behalf of Wirz, was told by an emissary from a high Cabinet official that if Wirz implicated Jefferson Davis in the atrocities committed at Andersonville, his sentence would be commuted. Allegedly, Schade repeated the offer to Wirz who replied, "Mr. Schade, you know that I have always told you that I do not know anything about Jefferson Davis. He had no connection with me as to what was done at Andersonville. If I knew anything of him, I would not become a traitor against him, or anybody else, even to save my life." The Rev. P. E. Bole received the same visitor and later sent a letter to Jefferson Davis, who included it as well as Wirz's reply to Schade in his book, Andersonville and Other War-Prisons (1890).[31] Andersonville quartermaster Richard B. Winder, who was in the prison at the time, also confirmed this episode.[4]

Execution

[edit]

Wirz was hanged at 10:32 a.m. on November 10, 1865, at the Old Capitol Prison in Washington D.C., located next to the U.S. Capitol.[2][citation needed] His neck did not break from the fall, and the crowd of 200 spectators guarded by 120 soldiers watched as he writhed and slowly strangled. Wirz was buried in the Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Wirz was one of only three men tried, convicted, and executed for war crimes during the Civil War (and, being a captain, was the highest-ranked of any executed),[2] the others being Confederate guerrillas Champ Ferguson and Henry C. Magruder.[32][33] Confederate soldiers Robert Cobb Kennedy, Sam Davis, and John Yates Beall were executed for spying; Marcellus Jerome Clarke was executed for being a guerrilla; and Andrew T Leopold was executed for spying, being a guerilla, and murder.[34]

In 1869, Schade received permission from President Johnson to rebury Wirz's body, which had been buried at the Washington Arsenal alongside the Lincoln assassins. While the body was being transferred, it was discovered that the right arm, and parts of the neck and head, had been removed during autopsy. As of the late 1990s, the National Museum of Health and Medicine still had two of his vertebrae.[12]

Controversy

[edit]

The Wirz controversy grew out of the questions remaining after his trial pertaining to guilt and responsibility for multiple deaths of prisoners of war in camps on both sides following suspension of the Dix-Hill Cartel prisoner exchange agreement in July 1863.

The Grand Army of the Republic, the United Confederate Veterans, Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), among others, evoked sad memories of Civil War prisoners portraying Wirz either a villain, or a martyr-hero, thus further contributing to the disputation. From 1899 to 1916, sixteen states erected monuments dedicated to the Camp Sumter's prisoners.[35] In response, the United Daughters of the Confederacy initiated a construction of a monument honoring Henry Wirz in Andersonville, Georgia.[35] Every year the UDC and SCV hold a memorial service at the monument.[36] Until recently, SCV annually marched to Wirz's memorial in Andersonville along with supporters of a congressional pardon for him.[37] The SCV posthumously awarded Wirz their Confederate Medal of Honor, created in 1977.[36]

During and after the trial Wirz was reviled in the court of public opinion as "The Demon of Andersonville".[38] One controversy concerns a witness for the prosecution, Felix de la Baume, who was actually Felix Oesser, a deserter from the 7th New York Volunteers (Steuben) regiment. According to the National Park Service, de la Baume was definitely a prisoner at Andersonville and it is a myth that he was a key witness at the trial.[27]

After time passed, some writers suggested Wirz's tribunal was unjust, stating that "Wirz did not receive a fair trial. Nevertheless, he was found guilty and sentenced to death."[39] In 1980, historian Morgan D. Peoples referred to Wirz as a "scapegoat."[40] Wirz's conviction remains controversial.[19][41]

Despite the surrounding controversy, the Wirz trial was one of the nation's significant early war crimes tribunals, creating enduring moral and legal notions and established the precedent that certain wartime behavior is unacceptable, regardless if committed under the orders of superiors or on one's own.[42][43]

In popular culture

[edit]Wirz is an important character in MacKinlay Kantor's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Andersonville (1955), introduced in the third chapter during his mission to France in October 1863. In Saul Levitt's 1959 play The Andersonville Trial, Wirz was first played by Herbert Berghof. When the play was recreated for an episode of PBS's 1970–71 season of Hollywood Television Theatre, Wirz was portrayed by Richard Basehart. Wirz was portrayed by the Czech actor Jan Tříska in the American film Andersonville (1996).[44][45][46]

See also

[edit]- Camp Douglas (Chicago) – Civil War camp in Illinois

- Concentration Camps – Imprisonment or confinement of groups of people without trial

- Fort Delaware – Fort in Delaware, United States

- Elmira Prison – US Civil War POW camp in New York State

- Libby Prison – Military prison in Richmond, Virginia, during the US Civil War

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Marvel, William (2006). Andersonville: The Last Depot. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5781-6.

- ^ a b c "Today in History - November 10". Library of Congress. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Henry Wirz in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ a b c Arch Fredric Blakey. Wirz, Henry, American National Biography Online, February 2000. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ Madison, James Page (1908). The True Story of Andersonville. New York and Washington: The Neale Publishing Company. p. 183.

- ^ a b c Stalder, Helmut (2011). Verkannte Visionäre: 24 Schweizer Lebensgeschichten (in German). Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung. p. 117. ISBN 978-3-03823-715-0.

- ^ Captain Henry Wirz, National Park Service

- ^ Tomes, R., & Smith, B. G. (1862). The war with the South: A history of the late rebellion, with biographical sketches of leading statesmen and distinguished naval and military commanders, etc. New York: Virtue & Yorston, Volume III, p. 685.

- ^ "Omnipresent and Omniscient: The Military Prison Career of Captain Henry Wirz - Andersonville National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ U.S. National Archives. "Compiled Service Record of Henry Wirz, Fourth Battalion of Louisiana Infantry". Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Louisiana. Footnote. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ Bergeron, Arthur W. Guide to Louisiana Confederate Military Units, 1861–1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989, pp. 157–158.

- ^ a b Schroeder-Lein, Glenna R.; Zuczek, Rischard (2001). Andrew Johnson : a biographical companion. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576070307.

- ^ Soldier Details: Wirz, Henry, General and Staff Officers, Non-Regimental Enlisted Men, CSA, Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Database, National Park Service

- ^ McPherson 1988, p. 802. Noting and contradicting the Georgian marker: the "percentage of deaths among inmates at Andersonville was in fact five or six times higher than among guards".

- ^ Davis, Robert Scott (2006). Ghosts and Shadows of Andersonville: Essays on the Secret Social Histories of America's Deadliest Prison. Mercer University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780881460124.

- ^ Page, Haley. (1908). p. 187.

- ^ See, e.g. testimony of Dorence Atwater; United States Congressional Joint Committee on Reconstruction, 1866, Virginia, North Carolina , South Carolina section, pg. 279-288

- ^ McPherson 1988, p. 796, noting acreage, lack of shelter, some 100 deaths per day in summer 1864, and fatality statistics of around 29 percent.

- ^ a b "Andersonville: Prisoner of War Camp - Reading 1". National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- ^ Maguire, Peter (2010). Law and War: International Law and American History. Columbia University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780231518192. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Trial of Henry Wirz, A Congressionally Mandated Report Summarizing the Military Commission's Proceedings, United States. 40th Congress, 2d Session. 1867–1868. House Executive Document No. 23, December 7, 1867.

- ^ United States Congressional serial set, Issue 3794, p. 785.

- ^ "The Norfolk Post. (Norfolk, Va.), 24 Aug. 1865". Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Court Martial of Henry Wirz, Charges and Specifications

- ^ a b "Witnesses Who Testified at the Trial of Henry Wirz". National Park Service. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Cloyd, Benjamin G. Haunted by Atrocity: Civil War Prisons in American Memory. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010.

- ^ a b "Myth: The Mystery of Felix de la Baume". National Park Service. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ "Duncan in Duress Circumstances Attending his Arrest". The New York Times. September 23, 1865.

- ^ "A summary of the trial of Henry Wirz" (PDF). Library of Congress. House of Representatives. 1866. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ "Report on the Wirz Trial by Judge Advocate General Holt". www.famous-trials.com. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Davis, Jefferson. Andersonville and Other War-Prisons. New York: Belford Co, 1890.

- ^ Hixson, Walter (2013). American Settler Colonialism: A History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-137-37425-7.

- ^ "Clipped From The Courier-Journal". The Courier-Journal. October 21, 1865. p. 3. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ "Military Execution [of Andrew Laypole] at Fort M'Henry," Pennsylvania Gazette, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 24 May 1864, p. 1, col. 5.

- ^ a b The Wirz Monument, National Park Service.

- ^ a b Alston, Beth (November 9, 2015). "40th annual Wirz Memorial Service held Sunday". Americus Times-Recorder. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Horwitz, Tony. Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War. New York: Pantheon Books, 1998, pp. 328–31.

- ^ The Demon of Andersonville; or, The Trial of Wirz, for the Cruel Treatment and Brutal Murder of Helpless Union Prisoners in his Hands. The Most Highly Exciting and Interesting Trial of the Present Century, his Life and Execution Containing also a History of Andersonville, with Illustrations, Truthfully Representing the Horrible Scenes of Cruelty Perpetuated by Him. Philadelphia: Barclay & Co., 1865.

- ^ Heidler, David Stephen, et al. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, New York: Norton, 2001.

- ^ Morgan D. Peoples, "The Scapegoat of Andersonville’: Union Execution of Confederate Captain Henry Wirz", North Louisiana Historical Association Journal, Vol. 11, No. 4 (Fall 1980), pp. 3–18.

- ^ Linda Wheeler. Wirz Took Controversial Fall for Andersonville Tragedy, The Washington Post, June 10, 2004.

- ^ Darrett B. Rutman, "The War Crimes and Trial of Henry Wirz," Civil War History, Vol. 6 (June 1960), pp. 117–33.

- ^ James C. Bonner, "War Crimes Trials, 1865–1867," Social Science, Vol. 22 (April 1947), pp. 128–34.

- ^ Thomas R. Flagel (2010). The History Buff's Guide to the Civil War: The best, the worst, the largest, and the most lethal top ten rankings of the Civil War. Sourcebooks. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-4022-5487-1.

- ^ Grant Annis George Tracey (2002). Filmography of American History. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-313-31300-4.

- ^ Brian Steel Wills (2011). Gone with the Glory: The Civil War in Cinema. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-4617-3957-9.

References

[edit]- Chipman, Norton P. (1911). The Tragedy of Andersonville; Trial of Captain Henry Wirz, the Prison Keeper. Sacramento.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Futch, Ovid (1968). History of Andersonville Prison. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813036915.

- Harper, Frank Roderick (1986). Andersonville: The Trial of Captain Henry Wirz. University of Northern Colorado.

- Marvel, William (August 1, 2006). Andersonville: The Last Depot. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5781-6.

- McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle cry of freedom: the Civil War era. The Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7.

- Page, James Madison; Haley, M.J. (1908). The True Story of Andersonville Prison. Neale (2000 reprint by Digital Scanning Inc.). p. 1122. ISBN 978-1582181479. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- Wooster, Robert (1998). Civil War 100. Carol Publishing Group. pp. 243–245. ISBN 9780806519555.

External links

[edit]- Entries from Wirz's diary made days before his execution

- Henry Wirz biography

- Documents suggesting Wirz's innocence

- Trial of Captain Henry Wirz, a class assignment for The Seminar in Famous Trials course at the University of Missouri-K.C. School of Law.

- 1823 births

- 1865 deaths

- American people convicted of torture

- Burials at Mount Olivet Cemetery (Washington, D.C.)

- Confederates convicted of war crimes

- Confederate States Army officers

- Confederate States Army personnel who were court-martialed

- Confederates executed by the United States military by hanging

- Crimes against prisoners of war

- Executed American mass murderers

- Executed military personnel

- Foreign Confederate military personnel

- Georgia (U.S. state) in the American Civil War

- Military personnel from Zurich

- People convicted of embezzlement

- People convicted of fraud

- People convicted of murder by the United States military

- People executed for war crimes

- Prisoners and detainees of Switzerland

- Swiss emigrants to the United States

- Swiss mass murderers

- Swiss people convicted of murder

- Swiss people executed abroad